The Thermidorian Reaction refers to the period of the French Revolution (1789-1799) between the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 27-28 July 1794 and the establishment of the French Directory on 2 November 1795. The Thermidorians abandoned radical Jacobin policies in favor of conservative ones, seeking the restoration of a stable constitutional government and economic liberalism.

The Thermidorians came to power by conspiring against and overthrowing Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794). After his execution, the Thermidorian regime set about dismantling the Reign of Terror by purging the Jacobins from positions of power and by violently suppressing their ideology in the First White Terror. Their efforts to return stability to France resulted in pursuance of conservative policies reminiscent of earlier phases of the Revolution; they restored freedom of religion, reintroduced free market capitalism, and allowed the return of some aristocratic émigrés into France, leading to a rise in openly royalist sentiment. These policies were met with mixed success.

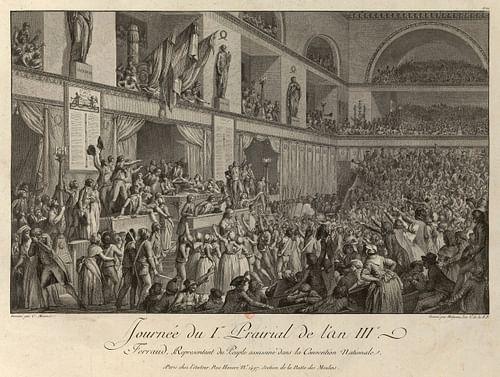

The new regime was generally unpopular with the French people, who faced increased rates of poverty and starvation during the 15 months of Thermidorian rule. This led to multiple attempted coups, the most significant of which was the Uprising of 1 Prairial Year III (20 May 1795), in which insurgents demanded bread and the adoption of the dormant constitution of 1793, which had been written by the Jacobins. After the uprising had petered out, the Thermidorians wrote their own constitution of Year III (1795), which established the French National Directory.

Thermidorians

The name 'Thermidorians', ascribed to the conspirators against the Robespierrist regime, is derived from the mid-summer month of Thermidor in the French Republican calendar, during which the coup took place. Though possessing a shared distaste for Robespierre, the Thermidorians had little else in common. Some of them had been willing and enthusiastic participants of the Terror before they had run afoul of Robespierre and needed to be rid of him to save their own skins. Others had detested the Terror from the start and had been eager to bring it down. Many were conservative republicans who represented the centrist mass of Convention deputies known as the 'Plain', who desired to turn back the clock to the way the Revolution had been in 1792, pre-Terror; others wished to go back further, seeking a second attempt at constitutional monarchy, as in 1791.

This lack of consensus, as well as the absence of dominating personalities to rally behind, contributed to the ineffectiveness and unpopularity of the Thermidorian Convention. The lackluster success of their policies has certainly marred the Thermidorians' legacy. Their detractors viewed them as an unremarkable interlude between Robespierre and Napoleon at best; at worst, they were the gravediggers of their own Revolution, one-time revolutionaries seduced and corrupted by the heights of power. This latter context was used by Leon Trotsky in his 1937 book The Revolution Betrayed, in which he refers to the rise of Joseph Stalin as a Soviet Thermidor.

While there may be elements of truth to these claims, historian Bronisław Baczko asserts that the Thermidorians were merely being realistic. The Revolution, having lost much of its momentum, grew closer to succumbing to fatigue with every month. It was becoming clearer that the Revolution could no longer live up to the promises made in 1789. Therefore, rather than willfully burying the Revolution, Baczko argues that the Thermidorians realized these limitations and simply did their best to work around them. After the violence of the Terror, many French people desired stability over revolutionary progress, which the Thermidorians attempted to give them. In either case, the period of the Thermidorian Reaction marked a counter-revolution of sorts, moving away from the radical progress of the Jacobins and back toward stable conservatism.

Fall of the Jacobins

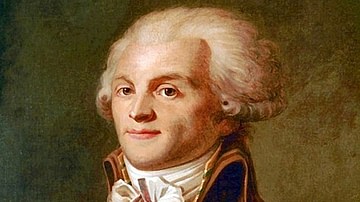

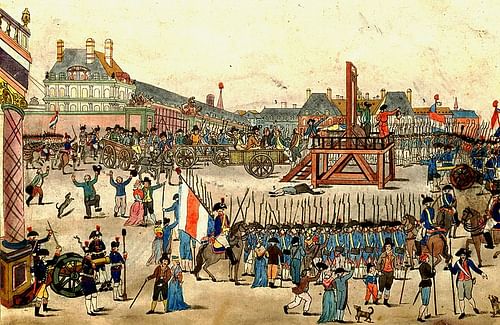

After months of bloodletting, France's Reign of Terror came crashing down on 28 July 1794 (10 Thermidor Year II) with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre. By then, the Terror had claimed somewhere between 20-40,000 lives, leaving much of France weary of the incessant slaughter. In his final days, Robespierre had accused certain members of France's provisional government, the National Convention, of counter-revolutionary conspiracy.

Although he did not name names, many Convention deputies had given Robespierre reason to dislike them, making them fear that their heads would be the next to fall. They decided to strike first and succeeded in toppling the overconfident Robespierre, who went to the guillotine after his jaw was shattered by a bullet. With Robespierre out of the picture, the conspirators, soon to be referred to as Thermidorians, decided to solidify their victory by ensuring the downfall of the Mountain (the Jacobins' political party) once and for all.

They began by dismantling the weapons of the Terror, and by punishing the men who had wielded them. The day that Robespierre died, the National Convention rejected a motion that the Committee of Public Safety be confirmed in its powers; instead, it was diminished to just one of many committees under the authority of the Convention. The Committee of Public Safety would still oversee the war effort but would cease to rule France.

Likewise, the Paris Commune was tamed when 70 of its officials who had remained loyal to Robespierre were executed without trial on 29 July. The Revolutionary Tribunal was temporarily kept in place, but the most fanatical of its staff were purged. Most notably, the dreaded chief prosecutor Antoine Fouquier-Tinville was arrested and later guillotined. Other Jacobins were unceremoniously removed from power, while the Thermidorians sent representatives-on-mission into the provinces to ensure the de-Jacobinization of the entire country.

On 1 August, the Thermidorians repealed the legal justifications of the Terror, namely the Law of Suspects and the Law of 22 Prairial, resulting in the release of thousands of prisoners who had been awaiting trial. 71 Convention deputies who had been arrested for supporting the Girondins in June 1793 were released and reinstated.

The Terror was declared to finally be over; the famous slogan "Terror is the order of the day" was replaced with a new one proclaiming "Justice is the order of the day". To exemplify this, only 6 people were guillotined in Paris during the entire month of August, a sharp contrast to the 342 who had been executed there the month before. The National Convention received close to 800 petitions praising it for dethroning the "scoundrel" Robespierre and hailing the Thermidorians as France's new founding fathers.

White Terror

However, there were those who were unsatisfied with the Thermidorians' promise of justice. Many who had recently been released from prison still felt bitterly towards the men who had put them there, while others had not forgotten the friends and loved ones they had lost to the guillotine. Many in France demanded revenge, not justice, be the order of the day.

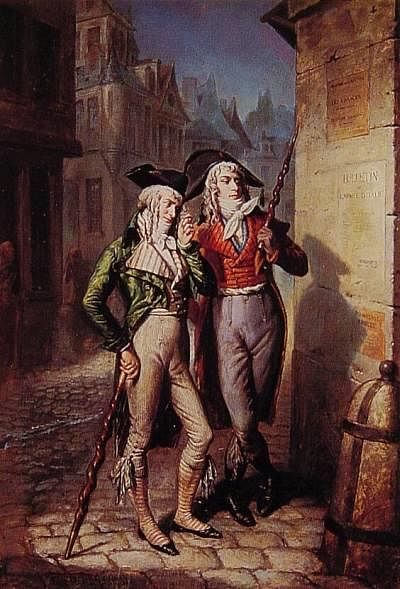

It was with this spirit of vengeance that certain anti-Jacobin groups began popping up in Paris and across France. One such group, known as the muscadins, strolled the streets of Paris, meting out vigilante justice at the end of wooden clubs. The muscadins (meaning "wearing musk perfume") were young men of the bourgeois class who assaulted known Jacobins in back alleys and instigated street fights with sans-culottes, the lower-class supporters of Jacobinism.

In mockery of Jacobin sensibilities, the muscadins deliberately dressed like caricatures of fops, donning wide-brimmed hats, overlarge cravats, and silk stockings. Egged on by Thermidorian-aligned newspapers, the muscadins broke up Jacobin meetings and even attacked the Jacobin Club itself in November 1794, beating up any man or woman they found inside. Rather than punishing the attackers, the Convention elected to permanently close the Jacobin Club instead, ostensibly to discourage future lawlessness. Shortly afterward, the Jacobin Club was officially outlawed.

Meanwhile, the Thermidorians continued cracking down on former Jacobin leadership. The same month the Jacobin Club was closed, Paris became enthralled by the highly publicized trial of Jean-Baptiste Carrier, perpetrator of the infamous drownings at Nantes. Thermidorian publications emphasized the barbarity of Carrier's crimes, making it out like he was representative of Jacobins everywhere. Carrier was executed in December, amid a brutal winter that brought about starvation, inflation, and unrest; these factors led to the failed insurrection of 12 Germinal, or 1 April 1795.

The Thermidorians responded to this uprising with renewed attacks on Jacobins. The Law of 10 April gave Thermidorian representatives-on-mission full authority to disarm and imprison suspects, leading to the arrests of as many as 90,000 suspected Jacobin sympathizers during the summer of 1795. Billaud-Varenne and Collot d'Herbois, two former members of the Committee of Public Safety, were indicted, tried, and deported to French Guiana, despite their assistance in overthrowing Robespierre. The message was clear: former Terrorists would be held accountable for their crimes.

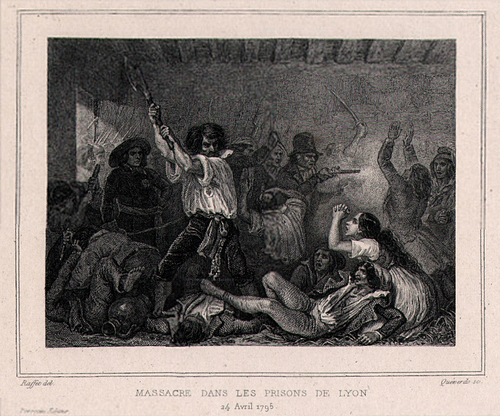

Street violence only worsened during this second wave of Jacobin repression in the spring and summer of 1795. Beatings by muscadins became more frequent, with one police spy reporting that, "it was enough to simply have the look of a Jacobin to be called after, insulted, and even beaten up" (Doyle, 285). But for some groups, simple beatings were not satisfactory. In the provinces, militias began to form with the goal of hunting down and butchering Jacobins; the so-called Company of Jesus fulfilled this purpose in Lyon, while the Company of the Sun hunted Jacobins in Nîmes. These groups usually forwent the orderly guillotine in favor of more personal ways of dispatching their enemies, such as lynch mobs, murder gangs, abductions, and ambushes. Since these militias tended to be led by royalists, this reactionary violence against Jacobinism has come to be known as the First White Terror (white being the color of the Bourbons, France's royal dynasty).

The White Terror, which lasted roughly from April to July 1795, saw the murders of close to 2,000 people. One noteworthy massacre occurred in Lyon on 4 May, when a large crowd invaded a prison and hacked 120 Jacobin prisoners to death. This was repeated a month later in Marseille, when the slaughter of 100 Jacobin inmates was perpetrated by angry mobs, coordinated by a Thermidorian representative-on-mission. Eventually, the violence petered out, and most of the 90,000 Jacobin prisoners were released by winter, relatively unscathed.

Thermidorian Policy

The Thermidorians first tried to reverse the Jacobin economic policy by repealing the Law of the General Maximum, which had put a price cap on bread and other essential supplies. The Thermidorians were generally pro-capitalist and believed that a return to free market economics would help revitalize France's economy, which was suffering badly from inflation.

Unfortunately, the Thermidorians implemented this policy at the worst possible time; the winter of 1794-95 was one of the worst in the 18th century for France. Without the regulation promised by the General Maximum, prices of bread and fuel skyrocketed, and the price of meat rose by 300%. Paris saw an uptick in deaths as people froze and starved to death or committed suicide to avoid such miserable fates. The Thermidorians responded by pumping out fresh batches of assignats, the Revolution's paper currency, but this only worsened the inflation problem. This failed economic policy would turn many against the Thermidorians and would cause some to feel nostalgia for the days of the Terror when bread was at least affordable.

Thermidorian policy fared better on the religious front. Attempting to scale back the programs of dechristianization that had flourished during the Terror, the Thermidorians declared freedom of worship in February 1795. They announced that the government would no longer pay for the upkeep of religious institutions, which effectively ended the Constitutional Church that had been established by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790; this also marked the first time in France's history that the church and the state were separated.

The Thermidorians extended this freedom of worship to the religiously conservative rebels of the War in the Vendée, who had revolted partly because of the Revolution's repression of Catholicism. The Thermidorian Convention also offered amnesty to any rebel who laid down his arms within a month of their proclamation. This did not end the rebellion, which continued until the Thermidorians sent in General Lazare Hoche who crushed it by 1796.

Rise of Royalism

The Thermidorians also pardoned many of the aristocratic émigrés who had fled France during the collapse of the Ancien Régime. Naturally, this led to a spike in royalist sentiment, as citizens no longer felt afraid to let their preference for monarchy known. The chaos of the Terror and the subsequent months of poverty under the Thermidorians had made the idea of protection under a stable monarch much more appealing than it may have been even six months before. The ideal candidate for kingship was Louis-Charles, the 10-year-old son of the executed King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792); the boy, already being hailed by royalists as Louis XVII of France, had been re-educated by revolutionaries and could possibly make for a dutiful citizen king who might honor the constitution in the way his late father had not.

Such a promising idea was torn apart when it was announced that the boy had died in June 1795, due to a combination of disease and likely neglect by his captors. The next best claimant to the throne was the boy's uncle, the Comte de Provence, who immediately began to style himself as King Louis XVIII of France. However, Louis XVIII refused to accept the throne without a promise that society as it had been under the Ancien Régime would be largely restored and that the regicides who had voted to execute his brother, Louis XVI, be punished. These conditions were unacceptable to the Thermidorians and most other citizens, and so the idea of restoring the monarchy was scrapped. Royalist sentiment continued to grow, however, and royalists would launch attempted coups against the government, such as the revolt of 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795) which was crushed by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).

Uprising of Prairial & Creation of the Directory

By the spring of 1795, the French Republic had been without a constitution for nearly three years. The democratic Constitution of 1793 had been written by the Jacobins but lay contained in a cedar ark, having never been implemented; starving, poor, and tired of the corruption of Thermidorian rule, Parisians rose up in insurrection on 1 Prairial Year III (20 May 1795), demanding bread and the Constitution of 1793.

They stormed the National Convention, killing and decapitating one deputy who confronted them and waving his head about on a pike. Growing bolder, the mob called for the arrests of both the returned émigrés and of the Thermidorians who had persecuted the Jacobins. Deputies of the Mountain began to side with the insurrectionists and echoed their demands. The following day, the 20,000 insurrectionists found themselves standing off against republican soldiers.

With neither side wanting to deliver the first blow, negotiations began; the insurrectionists agreed to disband if the Convention promised bread and the adoption of the constitution. The Convention promised the first of these at least, but after the mob disbanded, they reneged their promises, which they claimed had been made out of duress. The following days saw brutal attacks on the Parisians and National Guardsmen who had led the insurrection; thousands were arrested, the ringleaders guillotined. The 11 deputies of the Mountain who had supported it were also arrested, 6 of whom were condemned to death.

If the Thermidorians had ever considered adopting the constitution of 1793, such thoughts were put aside after the Prairial Uprising, since that constitution had become a rallying point for rebels and Jacobins. Moreover, there were aspects of the Jacobin constitution that the Thermidorians simply deemed to be unworkable. Instead, they went to work on their own constitution, which became known as the Constitution of Year III (1795). It contained things familiar to the Revolution, such as the seminal Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Yet it also differed greatly from its predecessors in certain aspects, such as introducing a bicameral legislature; this included the upper house of the legislature, the Council of Ancients, and the lower house, the Council of 500. Executive power was to be held by five Directors. The structure of this new Directory, containing a two-house legislature and multiple executives, was meant to ensure a separation of powers.

The Constitution of Year III was formally adopted on 22 August 1795, containing a staggering 377 articles, and would remain in place for the remainder of the Revolution. It was approved by a million voters, which was only a fraction of the roughly five million citizens eligible to vote, part of a continuing trend of low voter participation during the Revolution. There was one small problem for the Thermidorians, however; in the transition period between the outgoing National Convention and the incoming Directory, it was conceivable that royalists, or even Jacobins, could win a majority and thereby hijack the government. To counter this possibility, the Thermidorians ensured that two-thirds of the sitting members of the Thermidorian Convention would also serve in the Directory. Paul Barras, one of the original and most prominent Thermidorians, was elected as one of the five Directors.

The Directory, officially inaugurated on 2 November 1795, continued the Thermidorians' conservative push away from Jacobinism and sought to stabilize France. It oversaw French victories in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) but remained unpopular and was the target of several attempted coups. It was finally overthrown on 8-9 November 1799 in the Coup of 18 Brumaire; this coup, which launched Napoleon Bonaparte into power, is also often credited with being the end of the French Revolution.