Polynesian navigation of the Pacific Ocean and its settlement began thousands of years ago. The inhabitants of the Pacific islands had been voyaging across vast expanses of ocean water sailing in double canoes or outriggers using nothing more than their knowledge of the stars and observations of sea and wind patterns to guide them.

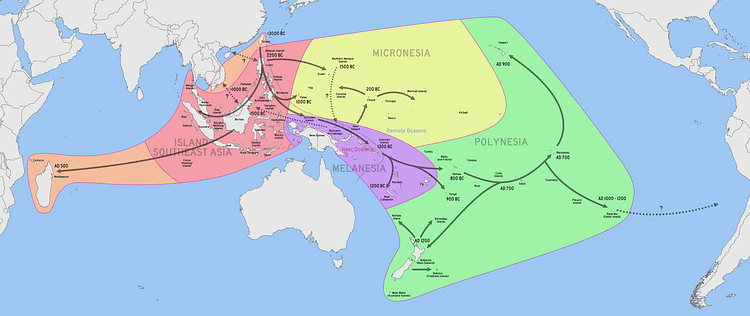

The Pacific Ocean is one-third of the earth's surface and its remote islands were the last to be reached by humans. These islands are scattered across an ocean that covers 165.25 million square kilometres (63.8 million square miles). The ancestors of the Polynesians, the Lapita people, set out from Taiwan and settled Remote Oceania between 1100-900 BCE, although there is evidence of Lapita settlements in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. The Lapita and their ancestors were skilled seafarers who memorised navigational instructions and passed their knowledge down through folklore, cultural heroes, and simple oral stories.

- was the migration and settlement of the Pacific islands and into Remote Oceania accidental or intentional?

- what were the specific maritime and navigational skills of these ancient seafarers?

- why has a large body of indigenous navigational knowledge been lost and what can be done to preserve what remains?

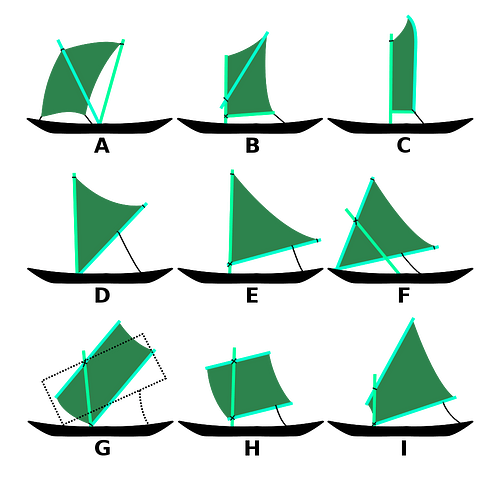

- what type of sailing vessels and sails were used to cross an open ocean?

Ancient Voyaging & Settlement of the Pacific

By at least 10,000 years ago, humans had migrated to most of the habitable lands that could be reached on foot. What remained was the last frontier – the myriad islands of the Pacific Ocean that required boat technology and navigational methods be developed that were capable of long-range ocean voyaging. Near Oceania, which consists of mainland New Guinea and its surrounding islands, the Bismarck Archipelago, the Admiralty Islands, and the Solomon Islands was settled in an out-of-Africa migration c. 50,000 years ago during the Pleistocene period. These first settlers of the Pacific are the ancestors of Melanesians and Australian Aboriginals. The small distances between the islands in Near Oceania meant that people could island-hop using rudimentary ocean-going craft.

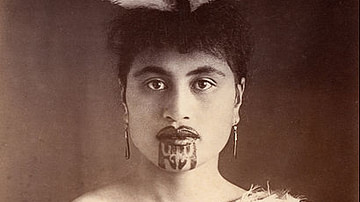

Collectively, these people are called the Lapita and were the ancestors of the Polynesians, including Maori, although archaeologists use the term Lapita Cultural Complex because the Lapita were not a homogenous group. They were, however, skilled seafarers who introduced outriggers and double canoes, which made longer voyages across the Pacific possible, and their distinctive pottery – Lapita ware – appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. Lapita pottery included bowls and dishes with complex geometric patterns impressed into clay by small toothed stamps.

Between c. 1100-900 BCE, there was a rapid expansion of Lapita culture in a south-east direction across the Pacific, and this raises the question of intentional migration.

Accidental or Intentional Migration?

The geographic area in Remote Oceania called the Polynesian triangle encompasses Aotearoa, Hawaii, and Easter Island as its corners and includes more than 1,000 islands. Between some of the islands in this triangle, there are distances of more than 1,000 kilometres (621 miles). Northern Vanuatu to Fiji, for example, is more than 800 kilometres (497 miles), and it would have taken tremendous skill and courage to sail in a canoe or outrigger for five to six weeks towards a hoped-for destination.

The prevailing European view was that any migration was the result of accidental storms or current drifts, not purposeful indigenous navigation. Pedro Fernandez de Queiros (1563-1614 CE), for example, wrote to the Viceroy of Peru in 1595 CE expressing incredulity that islanders with no maps or knowledge of the compass, and who had lost sight of land once they had set sail, could successfully navigate a long sea voyage (Lewis, 11).

Captain James Cook (1728-1779 CE), however, had little doubt that indigenous navigation demonstrated a high degree of skill. In the journal for his first voyage to the south Pacific Ocean in 1768-1771 CE he wrote:

…these people sail in those Seas from Island to Island for several hundred Leagues, the Sun serving them for a Compass by day, and the Moon and Stars by night. When this comes to be proved, we shall be no longer at a loss to know how the Islands lying in those Seas came to be peopled. (Cook's Journal)

Archaeologist Patrick Kirch points out that deliberate migration is the most likely scenario (Kirch, 137). The Lapita people may have been able to exist for months on remote Pacific islands living on wild birds and seafood, but the success of any long-term settlement would have necessitated transporting crop plants, such as taro and yam, as well as domestic animals. The sweet potato entered the Polynesian horticultural system c. 1000 CE and is strong evidence for Polynesian contact with South America – the reverse proposition to that of Thor Heyerdahl.

Recent voyages in replica canoes, along with computer simulations, have shown that the probability of accidental migration due to drifts (leading to a one-way voyage) is negligible. British-born New Zealand physician and adventurer David Lewis (1917-2002 CE), in his book We, The Navigators, sets out in detail the traditional indigenous navigation methods he used on his 1965 CE voyage in a catamaran or waka katea (double canoe) from Tahiti to Aotearoa. Using no modern instruments such as a compass, chronometer, sextant, or radio, he sailed 3603 kilometres (2239 miles) and made landfall with an error rate of only 41 kilometres (26 miles).

Crucial to the question of purposeful human settlement of the Pacific is the wayfinding skills of the Polynesian people because their navigational techniques allowed them to cross a vast ocean using little more than memory.

Indigenous Navigation Techniques

Unfortunately, most of the traditional Polynesian navigation knowledge has been lost for several reasons:

- most European explorers were sceptical of indigenous seafaring skills, and this was rooted in the deep sense of technological superiority of the Western narrative of the time.

- indigenous navigational knowledge was an oral tradition. It was not recorded systematically, and it was also considered secret knowledge, known only to certain families and fiercely guarded.

- European sailing techniques became dominant.

However, Polynesian folklore, cultural heroes, and simple oral stories known as aruruwow, have preserved some blue-water navigation information and ancestral knowledge. The legend of Kupe and his discovery of Aotearoa is an example that shows how aruruwow were memory aids that contained encoded instructions for reaching a specific destination.

In traditional Maori oral history, Kupe is a legendary figure and explorer of the Pacific Ocean (Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa) who set off from Hawaiiki in c. 1300 CE in a waka (canoe) to discover what lay over the horizon. Hawaiiki is the ancestral homeland of Maori and is thought to be in the East Polynesian islands. Kupe's navigator, Reti, followed a star path to hold the waka on course until it reached landfall in Whangaroa on the North Island of Aotearoa. There are several versions of the legend of Kupe, some involving Kupe chasing a giant octopus (Te Wheke-o-Muturangi) to the shores of Aotearoa, but what this aruruwow contains are references to stars, wind patterns, and currents that were memorised by generations of navigators.

Stars, Seas, Winds, Birds

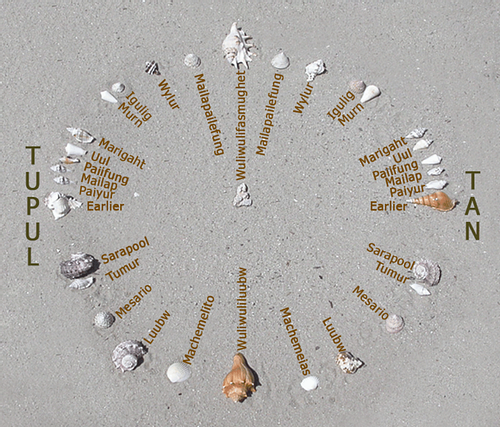

The Polynesians knew the language of the stars. They had a highly developed navigation system that involved not only observation of the stars as they rose and crossed the night sky, but the memorisation of entire sky charts. Throughout the Pacific, island navigators taught young men the skills acquired over generations. Navigational knowledge was a closely guarded secret within a navigator family, and education started at an early age. In Kiribati, for example, lessons were taught in the maneaba (meeting house) where rafters and beams were sectioned off to correspond to a segment of the night sky. The position of each star at sunrise and sunset and the star paths between islands were etched into memory. Stones and shells were placed on mats or in the sand to teach star-lore. Karakia (prayer) and oral stories contained references to navigation instructions. Te Ika-roa, for example, meant the Milky Way; Atua-tahi is Canopus; Tawera is Venus the morning star; Meremere is Venus the evening star. The following are navigational instructions from Kupe:

When you go, lay the bow of the canoe to the Cloud Pillar that lies south-west. When night falls, steer towards the star Atua-tahi. Hold to the left of Mangaroa and travel on. Whey day breaks, again sail towards the Cloud Pillar and continue on. (Quoted in Evans, 49)

Steering by the stars was the most accurate technique because the points on the horizon where stars rise remains the same throughout the year, even though stars rise earlier each night. A series of ten to twelve stars – a star path - were sufficient to guide the navigator. The star path from Tikopia (part of the Solomon Islands group) to Anuta (the easternmost island in the Solomons), for example, has nine stars.

- observing the colour and formation of clouds. A V-shaped cloud is sometimes seen over an island, and indigenous navigators knew that a dark under-belly to a cloud was reflected vegetation whilst a whitish underside indicated sand or coral reefs.

- observing the regular migration of birds or their flocking patterns. Fairy terns, for instance, fly no farther than 20-30 nautical miles (35-55 kilometres) from land.

- observing bioluminescence. Living sea organisms emit light that appears as streaks and flashes. Navigators from the Santa Cruz Islands referred to bioluminescence as te lapa or underwater lightning that acts as a compass towards land. Close to land, the movement of flashes is fast and generally indicates the canoe is 128-160 kilometres (80-100 miles) from land.

Voyaging Canoes & Sails

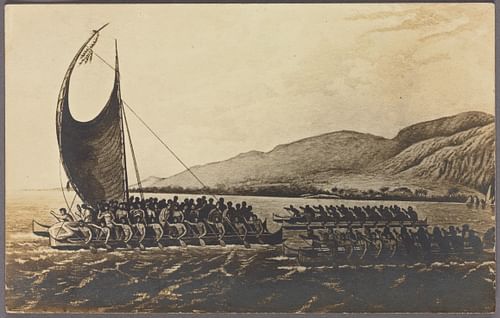

Polynesians mariners developed the double-hulled canoe (also called a catamaran). Some of their voyaging canoes were longer than Cook's Endeavour, which was approximately 30 metres (98 feet), although the average length for the canoes was 15.2-22.8 metres (50-75 feet). Canoes with an outrigger on one side were favoured in Micronesia (western Pacific region). The carrying capacity of the vessels was considerable. A Tongan double canoe could carry 80-100 people, while a Marquesan outrigger equipped for fishing or war could take 40-50 people.

Cook observed that the Tahitian pahi could sail faster than the Endeavour: “...their Large canoes sails much faster than this Ship, all this I believe to be true & therefore they may with Ease sail 40 Leagues a day or more” (Cook, A Journal of the Proceedings...).

Long-distance craft were sturdy planked vessels lashed together with braided sennit or twisted coconut fibre. Caulking material such as breadfruit tree gum made them seaworthy. Different types of canoes were used throughout Polynesia and Micronesia, but the three main types were the pahi, the tongiaki, and the ndrua. The pahi was a Tahitian two-hulled, two-masted vessel; the tongiaki from Tonga was a double canoe with triangular sails that was mistaken for a barque by the Dutch captain William Schoeten (c. 1567-1625 CE); and the ndrua was the double canoe with unequal hulls used in Fiji. Polynesian sails were the apex-down triangular sail; claw-shaped or crab-claw sails; and the lateen or triangular sail secured to two long booms. Sails were usually made from woven pandanus leaves.

Preserving Indigenous Knowledge

There has been recent effort to better understand and preserve the remarkable feats of seamanship that enabled Polynesians to steer their craft with accuracy across the vast expanse of the Pacific. In 1985 CE, a 22-metre (72 feet) voyaging waka christened Hawaikinui was built. Its twin-hull was constructed from two insect-resistant New Zealand totara trees, and the waka successfully sailed from Tahiti to Aotearoa using traditional Polynesian navigation techniques.

In 2018 CE, a young crew sailed a double-hulled voyaging waka from Aotearoa to Norfolk Island, off the east coast of Australia. Although they met with high ocean swells and unfavourable winds, the voyage was intended to teach young people the art of navigating by the stars and reconnecting with ancestral traditions. Polynesian navigation will have a modern renaissance through education and reconnection.