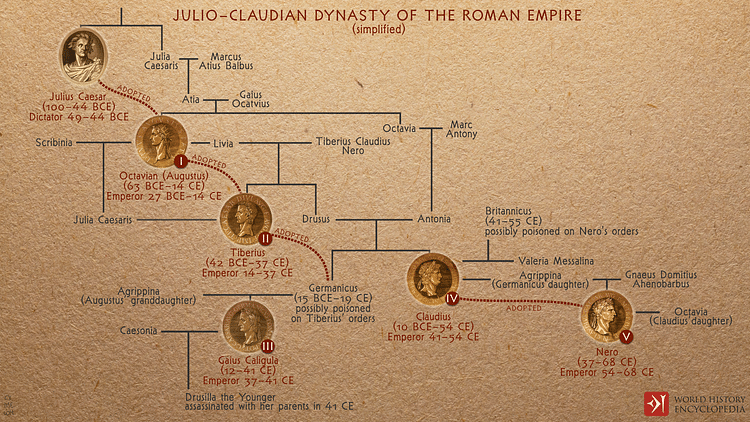

Tiberius was Roman emperor from 14 to 37 CE. Tiberius, the adopted son of Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus, never aspired to follow in his stepfather's footsteps — that path was chosen by his domineering mother, Livia. His 23-year reign as emperor would see him estranged from his controlling mother and living in self-imposed exile from the duties of running an empire.

In 42 BCE Tiberius Claudius Nero and his wife Livia Drusilla welcomed the birth of a son, Tiberius Julius Caesar. The marriage was a rocky one: the family was forced to live temporarily in exile because of Tiberius' father's anti-Augustus views. Historian Suetonius wrote in his The Twelve Caesars, “His childhood and youth were beset with hardships and difficulties because Nero (his father) and Livia took him wherever they went in their flight from Augustus.” When the young Tiberius was almost four, his parents divorced (Nero would die six years later), and his mother set her sights on another husband and father for her son — who better than the one-time enemy of her ex-husband, Augustus.

In 39 BCE Livia got her wish when she and Augustus were married. The marriage presented an opportunity for Tiberius to be in line for possible succession to the imperial throne, but at the time of the marriage, he was neither Augustus' favorite nor the next in line. Augustus had groomed his two grandsons, Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar, by his troublesome daughter Julia (her mother was wife number two, Scribonia) to succeed him. Later, however, to ensure his possible ascension to the imperial throne, Tiberius was forced to divorce (at Augustus' orders) his beloved, pregnant wife Vispania Agrippa (the daughter of Admiral Marcus Agrippa) and in 12 BCE to marry the recently widowed Julia.

Tiberius loathed his new wife but, luckily for him, her reputation (among other things, an adulterer) forced Augustus to exile her, even though Tiberius had unsuccessfully appealed to Augustus on her behalf. She met her death by starvation in 14 CE. While Tiberius did not mourn the death of Julia, he seemed even less than enthusiastic when Julia's two children died; Gaius in battle and Lucius by illness. While this placed Tiberius (by now the adopted son of Augustus) next in line, he had never demonstrated any excitement about becoming emperor — the excitement was all Livia's. It should be noted that Tiberius was in his forties when he was finally adopted, a practice not uncommon in Rome.

Tiberius' mother had loftier plans for her son. The historian Cassius Dio wrote:

… in the time of Augustus she [Livia] possessed the greatest influence, and she always declared that it was she who had made Tiberius emperor; consequently, she was not satisfied to rule in equal terms with him, but wished to take precedence over him.

Her controlling influence would not last. After Tiberius reluctantly became emperor — historians argue whether or not Livia had a hand in Augustus' death — Livia was removed entirely from public affairs and was even forbidden to hold a banquet in Augustus' memory. Tiberius refrained from having any future contact with her. When she died in 29 CE at the age of 86,

... Tiberius neither paid her any visits during her illness nor did he himself lay out her body; in fact, he made no arrangements at all in her honour except for the public funeral and images and some other matters of no importance.

The historian Tacitus added that Tiberius excused himself from the funeral “… on the ground of the pressure of business.”

The fact that Tiberius had never wanted to become emperor was evident. He had always excelled outside the political arena. He had been an excellent general, serving with distinction in Germany and holding the governorship of Gaul. However, in 6 BCE he abruptly went into self-imposed exile on the island of Rhodes (possibly to escape Julia), not returning to Rome until 2 CE — he had to request permission from Augustus to return. In fact, he was often referred to as simply “the exile.” In 14 CE Augustus died, allowing Tiberius to become the new emperor of the Roman Empire. As with many of those who followed him, his first few years as emperor went well. He shied away from much of the pageantry that followed his ascension, giving respect to the authority of the Senate. Cassius Dio wrote, “Tiberius was a patrician of good education (he spoke Greek fluently) but had a most peculiar nature. He never let what he desired appear in his conversation, and what he said he wanted he usually did not desire at all.” Considered a miser by some and modest by others, he began but did not finish many public works projects (most were completed later by Caligula). In his mind his assumption of the imperial throne was threatened by another: Germanicus Julius Caesar Claudianus, Tiberius' adopted son (at Augustus's request) and the true choice of many of the generals. Germanicus, however, silenced those outspoken opponents of Tiberius and voiced his support of the new emperor.

When Germanicus died suddenly after a brief illness in 18 CE, his widow, Agrippina the Elder, returned to Rome, believing Tiberius had ordered Gnaeus Piso, the former governor of Syria, to kill Germanicus. The young general had been responsible for Piso's ousting as governor. Piso was called to Rome to answer the accusations against him; however, despite an appeal to the emperor, he was forced to commit suicide. Agrippina also believed her sons — Nero Caesar, Drusus Caesar, and Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula) — should be considered next in line to the throne; however, this was never to be. Only Caligula would survive and become emperor. Drusus was starved to death and Nero was assassinated (Agrippina herself was exiled and eventually starved to death as well). Caligula and his sisters, who were seen as too young and not a threat, lived with Tiberius on Capri.

The death of Germanicus brought a change to Tiberius' personality; according to Cassius Dio, he became increasingly cruel “… towards those who were respected of plotting against him he was inexorable…slaves [were] tortured to make them testify against their own masters…” Tiberius would often pretend to pity those poor souls he had punished while he maintained a grudge against those he had pardoned. Suetonius concurred with this change of demeanor: “Tiberius did so many other wicked deeds under the pretext of reforming public morals but in reality (it was) to gratify his lust for seeing people suffer.”

The rigors of running an empire, combined with the interference of Livia, were too much for Tiberius, and he moved to the isle of Capri in 26 CE, leaving the daily routine to his advisor and prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Lucius Aelius Sejanus. As time passed Tiberius began to rely more and more on Sejanus' advice. Often seen by many as ruthless and ambitious, Sejanus even began to view himself as the true emperor, until he made a fatal mistake: Tiberius' son by Vispania (Julius Caesar Drusus) was married to a woman named Livillia (she was actually named after Livia). Sejanus who saw Drusus as a rival, began having an affair with his wife. Eventually, this led to Drusus' death in 23 CE by poisoning. At Livillia's insistence, Sejanus divorced his wife and left his children; the couple appealed to Tiberius in 25 CE for permission to marry, but Tiberius denied the request. By this time Sejanus had built the Praetorian Guard into a sizeable force of 12,000. Next, he embarked on a series of treason trials to weed out any possible opposition; many Romans lived in fear.

In 31 CE, without permission, the couple announced their betrothal. Livilla's mother, Antonia Minor, wrote the emperor and informed him of their intention to murder him and young Caligula. Tiberius hurried to Rome and appeared before the Senate, and Sejanus was lured to the Senate under false pretenses and forced to answer to the accusations. With little debate he was found guilty and condemned to death; he was strangled and torn limb from limb by an assembled mob, with his remains being left to the dogs. His sons and followers were also executed while Livillia was starved to death under the careful watch of her own mother.

In the last years of his reign, Tiberius grew more paranoid and imposed an ever increasing number of treason trials. He became more reclusive, remaining on Capri where in 37 CE he died at the age of 77 (supposedly at the hands of the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Naevius Sutorius Macro, with the help of Tiberius' eventual successor Caligula). Upon hearing of his death, the people, according to Suetonius, yelled “To the Tiber with Tiberius.” Cassius Dio said, “Thus Tiberius, who possessed a great many virtues, and a great many vices, and followed each set in turn as if the other did not exist, passed away in this fashion on the twenty-sixth day of March.”