The Maccabean Revolt of 167-160 BCE was a Jewish uprising in Judea against the repression of the Seleucid Empire. The revolt was led by a country priest called Mattathias, and his military followers became known as Maccabees. Successful, Jerusalem was captured and the Temple of Jerusalem reconsecrated, an act still commemorated today in the Jewish Hanukkah festival.

The Seleucid Empire

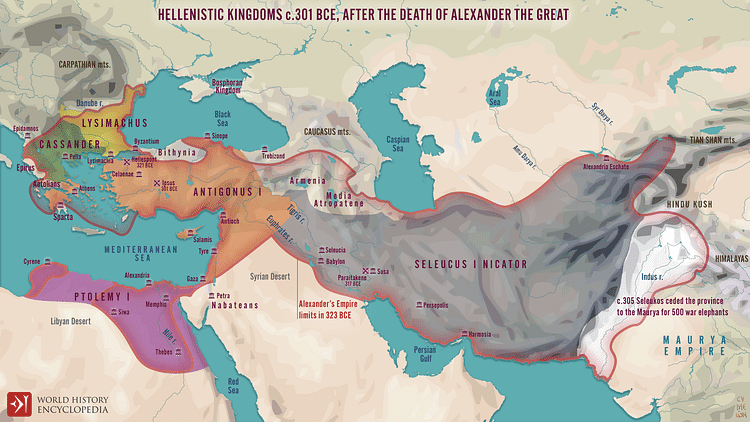

After the death of Alexander the Great, his kingdom was divided into four during the Wars of the Diadochi; Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, the Kingdom of Pergamon, and Macedon (including Greece). Egypt, governed by Ptolemy I Soter allowed for Judaism in Jerusalem to flourish with very little intervening in the 3rd century BCE. However, during the 2nd century BCE, the Seleucids, having gained dominance over Judea, went to enforce dominion over Egypt and the Jews.

Jews under Ptolemaic Rule

Theocracy and politics were intertwined in the 2nd century BCE in Jerusalem. The social structure of Jerusalem was run by the Jewish aristocracy such as the priests and the high priests. Although Hellenism, which had spread in the 3rd century BCE after Alexander's conquests, was the dominant culture around Judea and the Greek way of life pervaded the area, the Jewish community remained steadfast to their own practices. They largely ignored Hellenism and, under Alexander and the Ptolemaic Dynasty, were respected in doing so. The Ptolemies gave the Jewish people their civil rights, and they lived contently under their rule.

The Second Temple of Jerusalem was the most important structure to the entire Jewish community. It was the social and religious centre of the Jewish people, not to mention the economic benefits of trading in the Temple. More importantly, however, it was considered a sign of God's presence amongst them. This feeling of the elect, the chosen ones, was crucial to the Jewish self-consciousness.

Seleucid Takeover

In 198 BCE, all of the goodwill of the Jewish community towards the governing body turned to hatred as the Seleucid Empire defeated the Ptolemies, taking control of all Judea. As the Seleucid Empire expanded, so too did their notion of Hellenism. The Seleucids under Antiochus III controlled much of the Arabian Peninsula forcibly converting many of its new populace to Greek culture and religion, and the intent in that hegemony continued as they took Jerusalem. Antiochus wanted to Hellenize the Jewish community. His aim was to remove any features of Judaism that could define it from the Greek religion and other accepted monotheistic religions. Because of the benefits of the Greek culture, which included economic integration between all of the Greek states, and the pressure of regime, many Jewish people accepted Hellenism.

The already strained relations between the pious Jewish people that did not accept Hellenism and the Seleucid Empire were shattered when Antiochus Epiphanes adopted his father's policy of universal Hellenization but took it to new heights. As Epiphanes looked at Alexander the Great of Macedon and aspired to have his name in the history books alongside him, he needed to distinguish himself above his predecessors. The best way to do that, he thought, was to enforce the Greek culture on all of the Jewish population, a feat that had so far been elusive. He accepted a bribe and approved the takeover of Jason of the Oniad family to the now de facto client position of high priesthood.

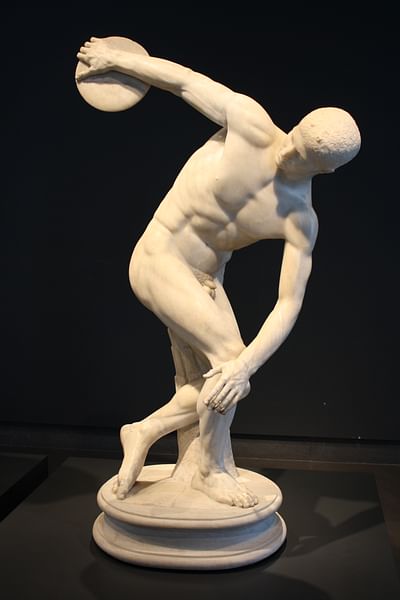

Antiochus used Jason's power as the High Priest over the Jewish people to build a gymnasium just outside the Temple, with that, strengthening the Greek culture in the heartland of the Jewish community. It was a symbol of Greek Hellenism and having it outside the Temple showed the Jewish community exactly who was in charge. The Hellenistic idea of masculinity was shown in the rule that one must be naked to enter the gymnasium. Being naked in public was strictly forbidden under Jewish laws, so any Jewish person that went into the gymnasium violated the laws of the covenant. The state understood this, and therefore, made it a legal requirement for anybody who could afford it to go at least once.

This was a method of making the state bigger and of greater authority than any other religion other than the Greek polytheism, thus many Jewish people fell in line and acquiesced to the regime. Antiochus, buoyed by his success of the gymnasium, decided to push harder against the Jewish religion. A short-lived rebellion took place, and when this was put down, Antiochus' views were hardened. He defiled the Holy Temple, vandalizing it and erecting an idol on the altar. He then outlawed certain practices such as circumcision and the Sabbath. Altars to Greek gods and idols were placed in every town, and those who did not pray to them and convert from practising Judaism were put to death.

Rebellion

Although many of the Jewish community were at this point Hellenized, the persecution of the Jewish people and the destruction of practicing Judaism united the Jewish people in Judea. The Jewish people needed someone to lead them. When Antiochus sent some of his officers to the town of Modiin to lay down his tyranny and enact the oppressive laws that he had enforced, he was met by a local Jewish country priest named Mattathias. This turned out to be a very portentous meeting. The country priest was ordered to fulfil his duty to the state and be the first to sacrifice an animal to an altar of an idol. He refused and when another Jewish man stepped forward to do it, he murdered the officer. Tearing down the idol, Mattathias preached "Let everyone who is zealous for the law and who stands by the covenant follow me!" (I Maccabees 2:27).

The Jewish people had their leader. He and his five sons, John, Simon, Judah, Eleazer, and Jonathan, rallied the Jewish population. In 167 BCE, the Jewish people rose up, with Mattathias as their leader. Soon after 167 BCE, the family of Mattathias became known as the Maccabees or the hammer. They recruited tough Jewish people on the way and began a guerrilla war as they started to take over the northern villages of Judea. They tore down the altars of idols and killed those who worshipped them, even many Hellenistic Jews. Mattathias died in 166 BCE but just before death, he left Judah in charge of his army.

Antiochus underestimated the severity of the rebellion and the size and strength of the Jewish army. Instead of crushing them with the full force of his armies, he set his less effective generals on them. Judah, a wise and courageous military general, defeated them with consummate ease. Antiochus was made to look foolish. As a response, he set out to exterminate the Jewish population in Judea. Antiochus sent for his most glorified general, Lysias, and around 60,000 Seleucid soldiers to try and do just that.

Judah was severely outnumbered. However, the familiarity of Judea was a huge advantage for the Jewish army. Using the slight hills and the superior knowledge of the area, they outmanoeuvred the Seleucids and slowly they picked them off. Finally, they came to battle. Judah had gathered another 7000 Jewish rebels, but they were still outmanned by at least five to one. As Judah stood there looking at the masses, so the story goes, he prayed to God for victory. The Jewish people overcame the massive difference in manpower to secure an almost impossible victory over the Seleucid Empire and over Antiochus.

After the defeat, Antiochus' armies were devastated. They met again when Judah's army was at the gates of Jerusalem, but it was a much shorter battle. The Seleucids were bereft of hope as Judah drove the enemy out of the Holy City. The Jewish army had defeated Lysias. When Judah and his brothers went to the Temple, he saw the destruction and defilement that Antiochus caused upon it and was overwhelmed by grief (I Maccabees 4:36-40). On 25 December 165 BCE, after months of work clearing and cleaning, the Temple was finally rededicated to God. Their celebrations continued for eight days as is known to this day as the celebration of Hanukkah.

Aftermath

The Maccabees had accomplished their pursuit of religious liberty and were going after political independence. Although the Jewish people supported their fight against the shackles of religious desegregation, they were unsure of the political and cultural influence of the Maccabees. The Hellenistic way of life was already entrenched onto the Jewish people. However, after the Maccabees conquered the whole of Judea and enforced the collapse of the Seleucid Kingdom in Palestine, the Jewish people imposed themselves as an autonomous group. Judea was now free from the Seleucid rule, and the death of Antiochus VII in 129 BCE confirmed this. The Jewish people were now content with the new political purpose of the Maccabees. Although no brother of Judah survived, with Simon being the last leader of the Maccabees who died in 134 BCE, their intention still flourished.

There is no general consensus on the nature of the revolt. Some see it as an economic and religious civil war, the Hellenised Jews that were propped up with the support of the Seleucids against the zealous who could only turn to their religion. Whilst others tend to think that it was more than a class victory; it was an example of success in fighting against oppression. The outcome, however, remained the same; the formation of the Hasmonean Dynasty, an autonomous Jewish rule over Palestine that would last a generation. The hopes of the Jewish monarchy were realised. So too was the freedom to practice the Jewish religion. This experience would be vital in the history of the Jewish people, particularly in Jerusalem in the following century.