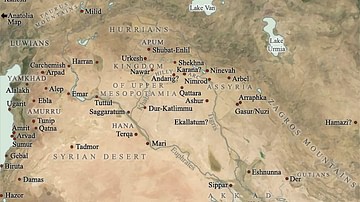

The Fertile Crescent, often called the "Cradle of Civilization", is the region in the Middle East which curves, like a quarter-moon shape, from the Persian Gulf, through modern-day southern Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and northern Egypt. The region has long been recognized for its vital contributions to world culture stemming from the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Levant which included the Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Egyptians, and Phoenicians, all of whom were responsible for the development of civilization.

Virtually every area of human knowledge was advanced by these people, including:

- Science and Technology

- Writing and Literature

- Religion

- Agricultural Techniques

- Mathematics and Astronomy

- Astrology and the Development of the Zodiac

- Domestication of Animals

- Long-Distance Trade

- Medical Practices (including dentistry)

- The Wheel

- The Concept of Time

The term was first coined in 1916 CE by the Egyptologist James Henry Breasted in his work Ancient Times: A History of the Early World, where he wrote:

This fertile crescent is approximately a semi-circle, with the open side toward the south, having the west end at the south-east corner of the Mediterranean, the centre directly north of Arabia, and the east end at the north end of the Persian Gulf. (193-194)

His phrase was widely circulated through the publications of the day becoming, finally, the common designation for this region. The Fertile Crescent is traditionally associated in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim faiths with the earthly location of the Garden of Eden. The area features prominently in the Bible and Quran and a number of sites there are associated with narratives from those works.

Cradle of Civilization

Known as the Cradle of Civilization, the Fertile Crescent is regarded as the birthplace of agriculture, urbanization, writing, trade, science, history and organized religion and was first populated c. 10,000 BCE when agriculture and the domestication of animals began in the region. By 9,000 BCE the cultivation of wild grains and cereals was wide-spread and, by 5000 BCE, irrigation of agricultural crops was fully developed. By 4500 BCE the cultivation of wool-bearing sheep was practiced widely.

The geography and climate of the region were conducive to agriculture and hunter-gatherer societies shifted to sedentary communities in the area as they were able to support themselves from the land. The climate was semi-arid but the humidity, and proximity of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (and, further south, the Nile), encouraged the cultivation of crops. Rural communities developed along with technological advances in agriculture and, once these were established, domestication of animals followed.

The first cities began to rise in Mesopotamia in the region of Sumer. Eridu, the first, according to the Sumerians, in 5400 BCE, then Uruk and others. By c. 4500 BCE cultivation of wheat and grains had long been practiced in addition to the further domestication of animals. By the year 3500 BCE the image of the breed of dog known as the Saluki was appearing regularly on vases and other ceramics as well as wall paintings along with breeds such as the Dane, Greyhound, and Mastiff.

The unusually fertile soil of the region encouraged the further cultivation of wheat as well as rye, barley, and legumes and some of the earliest beer in the world was brewed in the great cities along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers under the auspices of the goddess Ninkasi. Beer was considered a gift from the gods and a source of daily nutrition as well as an intoxicant. It was used to pay people's wages but inscriptions also make clear it was brewed for celebratory purposes and the famous Hymn to Ninkasi praises the brew for making one's heart feel light.

This beer was quite different from that of the modern day as it was thick and had to be consumed with a straw to filter out residue from the fermenting process. Beer brewing probably evolved from the baker's craft as the barley and wheat they stored fermented. The most ancient evidence of beer brewing comes from the Sumerian outpost settlement of Godin Tepe in modern-day Iran.

Emmer wheat, barley, chickpeas, lentils, and many other crops were planted, harvested, and sent to the temples where food supplies were stored. From c. 3400 BCE, the priests of the temple complexes were responsible for the distribution of food and the careful monitoring of surplus for trade.

Trade & Empire

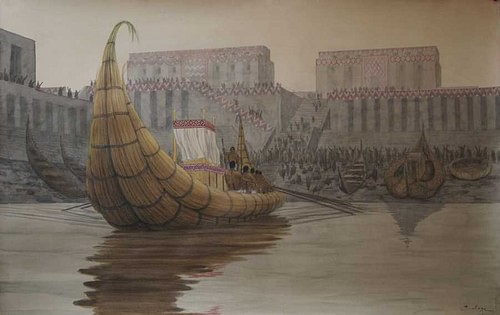

Trade routes grew up to form long-distance travel to the Kingdom of Saba in southern Arabia, Egypt, and the Kingdom of Kush in Africa. In time, this trade would establish the so-called Incense Routes which flourished between the 7th/6th centuries BCE and the 2nd century CE. The Incense Routes would facilitate cross-cultural exchange as merchants would carry innovations in various branches of knowledge along with their goods.

By 2300 BCE, soap was produced from tallow and ash and was in wide use as personal hygiene was valued in relation to one's standing with one's community and to honor the gods. Attention to one's person in terms of hygiene was stressed in that human beings were thought to have been created as help-mates to the gods and so should make themselves presentable in the performance of their duties.

As in Egypt, ritual bathing and personal grooming were especially important for the clergy. Those who attended to the gods were held to an even higher standard but, even for the most common laborer, cleanliness and grooming were important values. Artifacts from the region attest to this as mirrors, cosmetic jars, combs, hair brushes, and toothbrushes have been found as well as artistic depictions of bathing and inscriptions stressing its importance.

The people of the region lived in separate urban city-states until the rise of the first multi-cultural empire in the world: Akkad. From 2334-2279 BCE Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great) ruled over Mesopotamia, allowing for the growth of great building projects, artworks, and religious literature such as the hymns to Inanna by Sargon's daughter, Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE), the first author in the world known by name.

By 2000 BCE, Babylon controlled the Fertile Crescent and the region saw advances in law (Hammurabi's famous code), literature (The Epic of Gilgamesh, among other works), religion (the development of the Babylonian pantheon of the gods), science (astronomical measurements and technological developments), and mathematics.

From 1900-1400 BCE trade with Europe, Egypt, Phoenicia and the Indian sub-continent was flourishing, resulting in the spread of literacy, culture and religion to these regions. The goddess Nisaba, patroness of writing, grains, literacy, and wisdom, became known and worshipped in regions far from her native Sumer. Mesopotamian beer was a valued commodity in trade and many of the most important Mesopotamian deities traveled to other regions along the trade routes.

The Promised Land

It is speculated that it was in either 1900 or c. 1750 BCE that the biblical patriarch Abraham left his native city of Ur for the 'promised land' of Canaan carrying the tales and legends of Mesopotamian gods with him which would in time appear, transformed, as biblical narratives. If it was not in fact Abraham who diffused Mesopotamian myth and legend it was certainly someone like him. It is clear the parallels between stories such as the Mesoptamian Atrahasis and Noah's Flood, and the Myth of Adapa and the Book of Genesis' tale of the Fall of Man, among many others, share significant similarities.

Prior to the mid-19th century CE, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and the stories it contained were thought to be original pieces written by God or God-inspired. After archaeological digs in the region of the Fertile Crescent, however, and the discovery of the Sumerian civilization, it became clear that biblical narratives were derived from earlier Mesopotamian works. Mesopotamian religion and literature, in fact, would inspire and inform that of many other later cultures.

Changing Empires

The region changed hands many times through the ages. By 912 BCE the Assyrians controlled the Fertile Crescent and developed their vast empire. The Neo-Assyrian Empire was ruled by some of the best-known kings from antiquity including Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 BCE),Sargon II (722-705 BCE), Sennacherib (705-681 BCE), Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) and Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE). Ashurbanipal prized knowledge highly and ordered all the literary works of the region copied and stored in his great library.

When the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, the invading forces set fire to the libraries of the cities but, since the works were written on clay tablets, they were only baked harder, not destroyed. The invaders, inadvertently, were responsible for the preservation of the very culture they sought to destroy.

By 580 BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Chaldean Empire under Nebuchadnezzar II (634-562 BCE) was in power and Babylon flourished as the greatest city on earth. Allegedly, at this time, Nebuchadnezzar had the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon created for his wife to remind her of her homeland. In 539 BCE Babylon fell to Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE) after the Battle of Opis and the lands fell under the control of the Achaemenid Empire, also known as The First Persian Empire.

Alexander the Great invaded the area in 334 BCE and, after him, it was ruled by the Parthians, among others, until the coming of Rome in 116 CE. After the short-lived Roman annexation and occupation, the region was conquered by the Sassanid Persians (c. 226 CE) and, finally, by the Arabian Muslims in the 7th century CE.

By this time the glorious achievements of the early cities which grew up beside the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers had long been disseminated throughout the ancient world but the cities themselves were mostly in ruins through the destruction caused by the many military conquests in the region as well as natural causes such as earthquakes and fire. Rampant urbanization and the over-use of the land also resulted in the decline and eventual abandonment of the cities of the Fertile Crescent.

The city of Eridu, considered by the early Mesopotamians to be the first city on earth, built and inhabited by the gods, had been abandoned since 600 BCE, Uruk, the city of Gilgamesh, since 630 CE and Babylon, the city known for high culture, writing, law, science, and all manner of learning in the ancient world was a vacant ruin. Babylon's name would forever be linked to sin and corruption by the later Hebrew scribes who wrote the biblical narratives but, in its time, was greatly respected as a center of learning and civilization.

The Fertile Crescent Today

In 2001 CE the National Geographic News reported that the Fertile Crescent was rapidly becoming so only in name as, due to climate change, extensive damming of the rivers as well as a massive draining works program initiated in southern Iraq from the 1970's CE on, the fertile marshlands which once covered 15,000 – 20,000 square kilometers (5,800 – 7,700 square miles) had shrunk to a mere 1,500 – 2,000 square kilometers (580 – 770 square miles).

As pleas from environmental groups and regional farmers to stop damming and drainage projects were ignored by the governments of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, the situation worsened so that, presently, the region which once was the lush paradise and cradle of civilization largely consists of dry, cracked plains of sun-baked clay. Climate change, encouraged by fossil fuel emissions, has only worsened this situation.

Even after continued, long-term, threats to the environment were made clear to the governments of the region, no substantial efforts were made to preserve the land or reverse the damage. It has been observed by many scholars, historians, environmentalists, and writers through the centuries that human beings fail to learn from their pasts - whether individually or collectively. The philosopher George Santayana famously noted that "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it" and this paradigm rings as true for the Fertile Crescent as it does for any other region in the world today.