The Revolt of 13 Vendémiaire Year IV (5 October 1795) was a royalist uprising in Paris during the French Revolution (1789-1799). In response to the anti-royalist policies of the Thermidorian Reaction, 25,000 Parisians rose in revolt but were crushed by French Republican soldiers under the command of General Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), who famously used grapeshot to disperse the insurrectionists.

The goals of the rebels were just as anti-Thermidorian as they were pro-royalist. The Thermidorians were the faction that had overthrown Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794, ending the Reign of Terror. After taking control of Revolutionary France's provisional government, the National Convention, the Thermidorians implemented unpopular policies that worsened rates of starvation and poverty, causing many citizens to feel nostalgia for the comparatively stable days of the monarchy. As royalist sentiment rose, the Thermidorians passed a law that effectively prevented royalists from gaining a majority in the upcoming government, the National Directory. In response to this exclusion, 7 out of Paris' 48 sections rose in revolt on 5 October 1795, making their way toward the Tuileries Palace, where the Convention met.

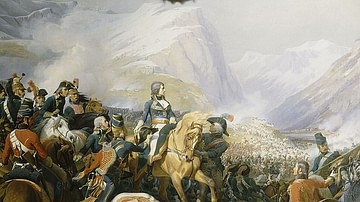

They never made it to the palace, as they were defeated by some 6,000 French soldiers commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte, at the time a young unemployed general. Bonaparte's actions would jumpstart his career, as his victory on 13 Vendémiaire would directly lead to him being offered command of the Army of Italy only five months later; his ruthlessness in suppressing the revolt would also be long remembered, immortalized by English historian Thomas Carlyle who wrote that Napoleon gave the insurrectionists a "whiff of grapeshot" (717).

Whispers of Revolt

The summer of 1795 found France in its sixth year of revolution. Much had happened since the Revolution had begun with the convening of the Estates-General of 1789; a monarch had been overthrown and executed, a republic had been declared, French citizen armies had battled the soldiers of Europe's Ancien Régimes, and a Reign of Terror had been imposed to rid the infant Republic of its enemies. Yet amidst these six eventful years of progress and chaos, of triumphs and failures, the people of France were still as poor and as hungry as ever.

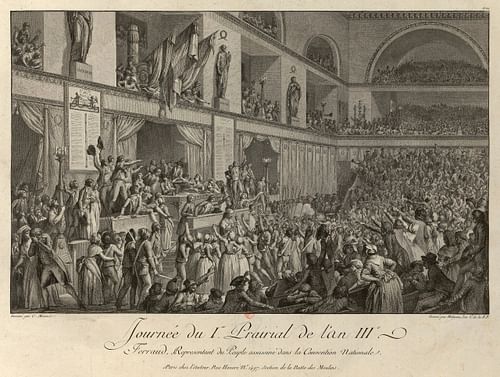

In Paris, the winter of 1794-95 was one of the most bitter in living memory. As the price of bread and firewood skyrocketed, people froze to death in their own homes or starved in the streets. Many blamed the conservative policies of the Thermidorian Reaction for the food scarcity, since the Thermidorians had reintroduced a free market economy right before the deadly winter chill had settled in. Some shivering citizens thought back fondly to the days of the Terror when bread and wood had at least been affordable. When spring came and there was still no food to be had, the people of Paris arose in a final popular insurrection, the Prairial Uprising, on 20 May 1795. They demanded bread and the Constitution of 1793, which had been written by the Jacobins during their time in power but had never been implemented.

The uprising was ultimately crushed, and its ringleaders were punished. Rather than adopt the Constitution of 1793, which had become a rallying point for dissent, the National Convention decided instead to write its own, more conservative Constitution of Year III (1795). This constitution, comprised of a staggering 377 articles, introduced a new government to the Republic which would be known as the French Directory; this would include a bicameral legislature consisting of an upper house, the Council of Ancients, and a lower house, the Council of 500. Executive power would be split between five elected Directors, to ensure a separation of powers. The constitution was adopted on 22 August 1795, and the Directory was slated to go into effect on 2 November.

There were factions within France who saw the upcoming government transition as a prime chance to gain power. One such group was the royalists, who only a year before had been forced into hiding to avoid an unfortunate meeting with the guillotine. In August 1794, after the end of the Reign of Terror, French aristocrats and émigrés who had fled France during the collapse of the Ancien Régime had been pardoned and invited back, making many royalists feel safe enough to openly voice their preference for a monarchy. The movement grew during the disastrous winter of 1794-95, as many began to view the restoration of the monarchy as a fair trade for food in their bellies and a stable government. Naturally, it was not the oppressive Ancien Régime of 1789 they advocated for, but a more liberal, constitutional monarchy akin to the one France had briefly experimented with in 1791. Some royalists hoped to win election to the Directory so that they could peacefully bring such a government into existence.

Royalism Outmaneuvered

The outgoing National Convention was not blind to this rise in royalist sentiment. While the Convention may have been a more conservative body under the Thermidorians than it had been under Jacobin rule, that did not mean it was ready to hand power back to the royalists and see the death of the Republic. To prevent a royalist majority from taking root in the Directory, the Thermidorians enacted the Two-thirds Law, which stated that two-thirds of the deputies currently sitting in the National Convention must also serve in the Directory. This would guarantee a Thermidorian majority in the next government, no matter the results of the other elections.

The Two-thirds Law shocked the public, who had become sick of the Convention and its corrupt dealings. The unrest was palpable on 10 August, when a festival held by the Convention to honor the third anniversary of the toppling of the monarchy was met with lukewarm enthusiasm. One police spy reported the reason for this lack of celebrating: "Market women said it would have been better to do something about bringing down the price of things instead of holding useless and expensive festivals" (Doyle, 320-21). Although the Two-thirds Law had been marketed as "a decree on the means to put an end to the Revolution", it dashed all hopes that France would be rid of the corrupt and tiresome Convention; now, the Directory would see the same people in power, just with different packaging.

The Two-thirds Law was unpopular across France. A quarter of the provinces opposed it, as did all but one of Paris' 48 sections. These sections had become significantly more conservative than they had been during the Prairial Uprising back in May, as the National Convention had arrested or removed most of the leftwing leaders who had participated in that insurrection. The unforeseen result was that these new conservative leaders began to turn against the Convention as well, unhappy with its blatantly anti-royalist stance.

Throughout Paris, right-wing newspapers circulated, denouncing the Two-thirds Law and demanding a return to a constitutional monarchy. As a counterbalance, the Convention ordered the release of leftist Jacobin and sans-culotte leaders imprisoned after Prairial, hoping that these natural enemies of royalism would take care of the problem for them. But it was too late. In late September, the sections' various assemblies had already declared themselves to be in permanent session and disregarded the Convention's orders to disperse.

A Royalist Revolt

On 3 October, a royalist riot erupted at Dreux, 40 miles west of Paris, and was violently crushed by Republican soldiers. News of the incident spread to Paris the next day, and a call went out for representatives of each of the sections to meet and begin planning their course of action. Only 15 of the 48 sections ended up meeting, but this was a large enough portion of the city to alarm the Convention, which positioned soldiers at key locations. On the morning of 4 October, seven of the sections declared themselves to be in open insurrection and began mobilizing their National Guards.

The Convention entrusted the defense of the city to General Jacques-François Menou, who was given only 5,000 men; by contrast, the royalists were said to number upwards of 20,000. In the evening, Menou sent his troops to the section of Le Peletier, which was the center of the resistance. Rather than risk a violent confrontation with Menou's regular troops, the royalists promised to disarm. Menou, also eager to avoid a battle, agreed to take them at their word and withdrew. Of course, these promises were not kept. By the next morning, some 25,000 royalists had gathered south of the Seine River and began a march toward the Tuileries Palace, where the National Convention convened. Menou was relieved of command and was replaced with Paul Barras, a prominent Thermidorian who was set to take a leading role in the upcoming Directory.

Having not held a military command since 1783, Barras was certainly out of his element and knew he would need help if he was to adhere to his instructions to "save the Revolution" (Roberts, 65). Fortunately, Barras was already acquainted with a young officer who may be able to do the dirty work for him, one who had brilliantly distinguished himself at the Siege of Toulon. In the small hours of the morning of 5 October, as the royalist insurrectionists were gathering, Barras sent for Napoleon Bonaparte.

Enter Bonaparte

In October 1795, Napoleon Bonaparte was a 26-year-old brigadier general looking for a job. Born on the island of Corsica, he spent his boyhood being educated in French military schools. As an artillery officer, he had played a vital role in retaking the port city of Toulon from the British in 1793, an action that led to his promotion to brigadier general at only 24. Yet despite his promising abilities, his previous association with Augustin Robespierre and the now disgraced Jacobins made it difficult for him to find a suitable command; the autumn of 1795 found him living in Paris, working for the Topographical Bureau, which was essentially purgatory to an officer as ambitious as Bonaparte.

On the evening of Sunday 4 October, Bonaparte was at the Feydeau Theatre watching a play, when he heard whispers that the sections planned to rise in insurrection the following day. Only hours later, he was summoned by Barras, who had been impressed with the stories of Bonaparte's exploits at Toulon. As biographer Andrew Roberts notes, it is a quirk of fate that there were no senior officers in Paris who were willing to accept the command; perhaps it was just that Bonaparte had the least qualms about firing on civilians. Three years before, during the Demonstration of 20 June 1792, Bonaparte had wondered why the king's Swiss Guards had allowed the demonstrators to march on the Tuileries and harass the king with such impunity, asking, "why do they not sweep away four or five hundred of them with cannon? The rest would take themselves off very quickly" (Roberts, 39). He had attributed the subsequent fall of the monarchy to the Swiss Guards' lack of decisive action; now, Bonaparte was not about to make the same mistake.

He accepted the command from Barras on the condition he would have complete freedom of movement. Once granted, the young general immediately went to work. He ordered sous-lieutenant Joachim Murat of the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval regiment, to go to the Sablons military camp two miles away with 100 cavalrymen. Murat was to secure the cannons there and take them back to Paris in all haste; he was to saber anyone who got in his way. If the insurrectionists had also thought of the cannons and sent men to secure them, Murat got there first and hauled the artillery pieces into the city as instructed.

Between 6 and 9 in the morning, Bonaparte prepared the city's defenses. He handpicked officers and men whose loyalty he could depend on. When Murat returned with 40 cannons, Bonaparte positioned them at key defensive points. Next, Bonaparte lined up his infantry behind the cannons and sent reserves to defend the Tuileries Palace itself should the royalists overwhelm his line. Finally, he placed his cavalry on the Place de la Revolution, where the blood of suspected traitors had so freely flowed during the recent Terror. General Bonaparte himself spent the rest of the morning riding between these positions, making certain everything was ready. He was prepared to do everything in his power to achieve victory; he would later defend his actions that day by writing: "Good and upstanding people must be persuaded by gentle means. The rabble must be moved by terror" (Roberts, 66).

“Whiff of Grapeshot”

By early afternoon, the royalist mob had gathered, numbering between 25-30,000 people. The only thing standing between them and the Convention deputies at the Tuileries was 4,500 regular troops and 1,500 gendarmes commanded by General Bonaparte. For hours, the insurrection's leaders engaged in fruitless negotiations with the Republicans; by the time they realized that they would get nowhere with words alone, it was 4 p.m., and the insurrection had lost its momentum. It was only then that the rebel column began inching its way forward, tentatively, toward the Republican lines.

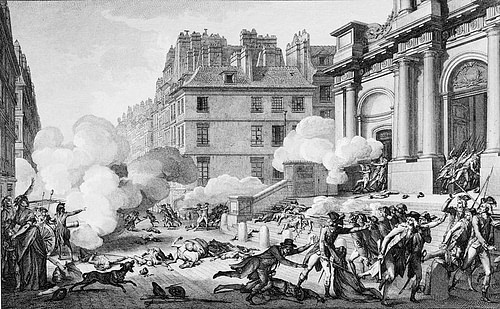

Thanks to the previous Prairial Uprising, the Paris sections had been thoroughly disarmed by the Convention. The sections had no cannons and what rifles they did have were short on powder and shot. Still, they had the advantage of numbers. To his credit, Bonaparte held off on giving the order to fire until he was certain there would be no alternative. Sometime between 4:15 and 4:45 in the afternoon, musket shots were heard emanating from the royalist lines. Bonaparte answered with his artillery.

The Republican cannons had been loaded with canister shot, which consists of hundreds of musket balls packed inside a metal casing that tears open as soon as it is fired from a cannon. These projectiles are hurled at a velocity even greater than that of a normal musket shot, at a maximum range of 600 yards; colloquially, canister shot was referred to as grapeshot. Prior to 13 Vendémiaire, to use grapeshot on a civilian population, even one in the midst of insurrection, was unheard of. Yet Napoleon Bonaparte was never one to shy away from originality.

As the men of the sections attempted to cross the bridges over the Seine, they were met with a "whiff of grapeshot", a phrase later coined by English historian Thomas Carlyle to describe the encounter. The canister tore through fabric and flesh and bone, sending heaps of royalists flying to the ground, screaming. As the bodies piled up, the royalist advance was further slowed, and the rebels were pinned down on the bridges or in the streets with nowhere to go. Panic mounted as the steady crack of rifle fire from the Republican infantry echoed. In most of the city, the grapeshot had done the trick and the insurrection had mostly ended by 6 p.m.

At the church of Saint-Roch, which had become the headquarters of the insurrection, fighting continued well into the night. Snipers hiding on rooftops or behind barricades picked off royalists as they came back with their wounded. The church continued to hold out until Bonaparte brought up his cannon within 60 yards; the royalists then chose surrender over obliteration. After six hours of scattered fighting, the battle was over. Around 300 royalist insurrectionists had been killed, and hundreds more wounded. The Republicans had lost only 30 killed and around 60 wounded. It was a resounding victory for the National Convention, which would transition into the National Directory less than a month later, the Two-thirds Law having been implemented. The people of Paris would not mount a serious threat to the government again for the remainder of the Revolution.

Aftermath

The suppression of the royalists after Vendémiaire was less severe than the suppression of the Jacobins had been after Prairial. Only 2 section leaders were executed, although it was left to General Bonaparte to oversee the expulsion of some royalist sympathizers from the ministry and to police theatre productions. The Revolt of 13 Vendémiaire is most notable for its importance in the story of Napoleon himself. Barras was so impressed with Bonaparte's conduct, that he ensured the young general's appointment to the command of the Army of Italy only five months later, which was the command that would make Napoleon famous. Through his newfound friendship with Barras, Napoleon was also introduced to the widowed Joséphine de Beauharnais, who had briefly been Barras' mistress. Napoleon and Joséphine were married in March 1796, sparking one of the most famous (and complicated) romances of the early 19th century.

More immediately, Bonaparte's conduct on 13 Vendémiaire greatly increased his family's prestige. He was awarded an annual salary of 48,000 francs, and his brother, Joseph, was given a job in the diplomatic service. His ruthlessness in suppressing the rebellion would long be remembered, and some would derisively refer to him as "General Vendémiaire" behind his back. Far from attempting to hide this bloody chapter in his history, Bonaparte would order the anniversary of the victory to be nationally celebrated once he became First Consul, defending the slaughter by stating, "A soldier is only a machine to obey orders" (Roberts, 67). But as biographer Roberts notes, Napoleon failed to mention that he was the one who had given the orders.

For Thomas Carlyle, the Revolt of 13 Vendémiaire marked the end of the French Revolution, as it was the moment when "the thing we specifically call the French Revolution is blown into space" (717). While the revolt certainly marked a turning point, a definitive end to popular uprisings, many modern scholars agree that the aging Revolution itself would linger on for four more years, trapped in a state of limbo, until it was finally put out of its misery by Bonaparte himself in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, in November 1799.