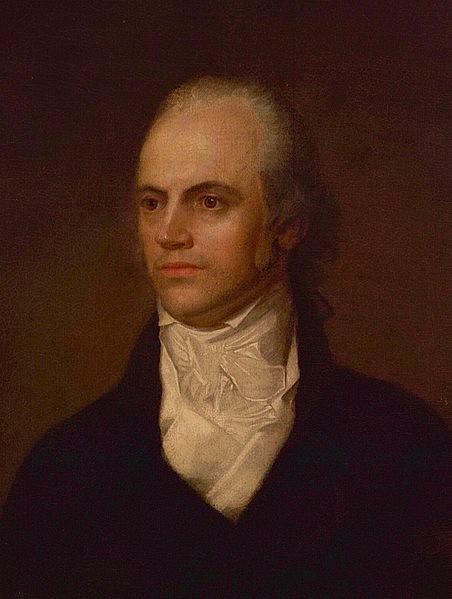

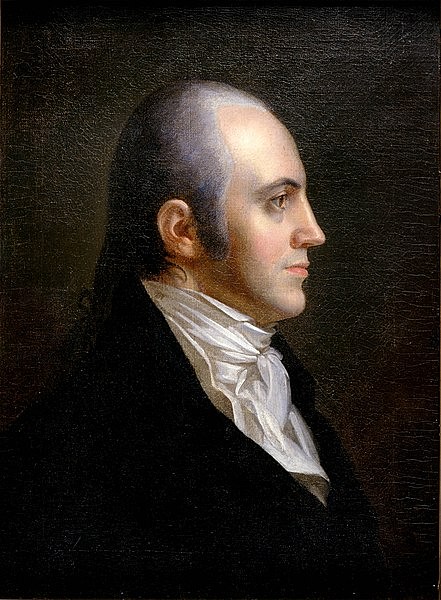

Aaron Burr (1756-1836) was an American politician and lawyer, who served as the third vice president of the United States (1801-1805). His reputation as a US Founding Father was marred by his killing of political rival Alexander Hamilton in a duel and by his treason trial in 1807, leading to his common depiction as a villain in US history.

Early Life & Revolution

Aaron Burr, Jr. was born on 6 February 1756 in Newark, New Jersey. He was the second child of Aaron Burr, Sr. a distinguished Presbyterian minister and second president of the College of New Jersey (modern-day Princeton University), and Esther Edwards Burr, the daughter of famed theologian Jonathan Edwards. Burr would never know his parents, however; in 1757, his father died of a sudden fever, and his mother fell ill and died a year after that, leaving Burr orphaned at the age of two. He and his elder sister, Sarah Burr, were sent to live with their wealthy maternal uncle, Timothy Edwards, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. A successful lawyer, Edwards hired private tutors to educate the young Burr and prepare him for eventual enrollment at Princeton. However, Edwards was also physically abusive towards his foster children, causing Burr to try to run away from home several times.

Burr was admitted into Princeton in 1769 at the age of 13. Initially, he decided to follow in his grandfather's footsteps and study theology. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree at the age of 16, but, after two more years of religious study, eventually opted to abandon theology in favor of a law career. In 1775, 19-year-old Burr was studying law in Connecticut when he learned of the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April) and the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. He immediately enlisted in the Continental Army, and, that autumn, he served under Colonel Benedict Arnold in the ill-fated American invasion of Quebec. To get to the British colony of Quebec (Canada), Arnold's men had to trek 300 miles (480 km) through the wilderness of Maine, an odyssey that Burr endured with 'great spirit and resolution'. Upon reaching Canada, Arnold linked up with General Richard Montgomery for an assault on the city of Quebec. During the climactic Battle of Quebec (31 December 1775), Burr was standing nearby when General Montgomery was killed by a blast of grapeshot. Burr risked his life trying to retrieve the general's corpse, but had to abandon it when he could not drag it through the fast-piling snow.

Promoted to major for his bravery in the Quebec campaign, Burr was sent to join the staff of General George Washington in the spring of 1776. The two men quickly fell afoul of one another – Burr, who had wanted to help plan military strategy, was insulted to find that he would be relegated to performing menial tasks, while Washington disliked the young officer's haughty personality. In June, Burr was transferred to the staff of General Israel Putnam and became his aide-de-camp. Following the disastrous Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776), Burr played a crucial role in the evacuation of the Continental Army first from Long Island, then from New York City, with his leadership credited for salvaging the American artillery. In July 1777, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of a regiment of 300 men. He was with the army during the harsh and bitter winter at Valley Forge and was present at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778), where his regiment was devastated by British artillery. Burr suffered a debilitating sunstroke during the battle that hindered him from carrying out his soldierly duties. This, and other health issues, led him to resign from the Continental Army in March 1779.

Rising Star

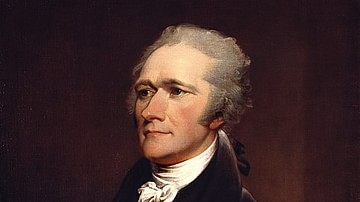

After leaving the army, Burr went to Albany, New York, to complete his legal studies, and was admitted to the bar there in April 1782. He practiced law in Albany until November 1783, when he moved his burgeoning practice to New York City after the last British troops evacuated the city at the end of the war. There, he strove to outperform several other promising young lawyers, including Alexander Hamilton – while Burr himself considered Hamilton to be the better speaker, Burr was often seen as the better all-around lawyer. "As a lawyer and a scholar, Burr was not inferior to Hamilton," a contemporary once remarked. "I used to say of them…that Burr would say as much in half an hour as Hamilton said in two hours. Burr was terse and convincing, while Hamilton was flowing and rapturous" (quoted in Chernow, 193). As his star was rising in the legal field, Burr found time to get married; in July 1782, he was wed to Theodosia Prevost, a widow ten years his senior. Together, they would have one daughter, also named Theodosia.

Now, at 27 years old, Burr certainly seemed poised to make a name for himself on the stage of American politics. He was handsome and witty, traits that helped the rakish Burr in his many seductions. Like Hamilton, he enjoyed the finer things in life and would accept nothing less than the best wines, most elegant coaches, and most fashionable clothes. But unlike many of his contemporaries, Burr was no idealist; while men like Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson viewed politics as a means to enact their desired policies, Burr was more interested in the game of politics itself. Ever the opportunist, he primarily saw politics as a tool to win money and influence for himself and his friends, once describing politics as nothing more than "fun and honor and profit" (quoted in Wood, 280). This meant that Burr held his true opinions close to his chest and gave off an impression that he was a political chameleon, willing to switch to whichever side would most benefit him. This approach to politics earned Burr the disdain of idealistic men like Hamilton, who once said of him "in civil life, he has never projected nor aided in producing a single measure of important public utility" (quoted in Chernow, 193).

Burr entered politics for the first time in 1784 when he was elected to the New York State Assembly. During his brief tenure, he proposed a bill that would free all slaves born after a certain date – this despite the fact that Burr himself owned five household slaves and had no intention of freeing them. The bill did not pass. In 1789, Burr was appointed New York state attorney general, an office that won him the attention of the influential Livingston and Clinton political dynasties. With their backing, Burr was elected to the US Senate in 1791, defeating the incumbent Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law.

He served in the Senate for the next six years, during which time he aligned himself with the Democratic-Republican Party (also known as Jeffersonian Democrats). There had been a growing rift in US politics between the nationalist Federalist Party – which supported a strong national government, industrialization, and pro-British policies – and the Democratic-Republicans, who believed in more autonomy for the states, an agrarian economy, and supported the French Revolution. By backing the Democratic-Republicans, Burr was allying himself with men like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and was opposing Hamilton, the leading Federalist.

As early as 1795, Burr was sounding out a potential presidential run, visiting influential Democratic-Republicans across the country. He even spent a day at Jefferson's home of Monticello, although it is not known what they discussed. In September 1796, President Washington formally announced that he would not seek a third term of office, kicking off the US presidential election of 1796. Although it was considered uncouth for a candidate to campaign for himself, Burr did exactly that, travelling through the northern states to drum up support. It was not enough; he came in fourth place with 30 electoral votes. John Adams, the Federalist candidate, won the presidency, with Jefferson becoming vice president.

Burr was already dismayed by his loss, but insult was added to injury when he learned that he had lost his Senate seat to Philip Schuyler. Frustrated, Burr returned to state politics, winning re-election to the New York State Assembly in 1798. In September 1799, he founded a bank called the Manhattan Company, thereby destroying the Federalists' monopoly on banking in New York. Burr managed to avoid any Federalist opposition by claiming that the purpose of the Manhattan Company was to provide water for New York City; it was only at the last minute that he amended the company's charter, revealing that it was, indeed, a bank. Hamilton and the Federalists were outraged, accusing Burr of having acted dishonorably by deceiving them in such a way.

Vice President

In the months preceding the US presidential election of 1800, Burr once again decided to run, this time campaigning to be Jefferson's vice president. Using his political connections, he was able to flip New York for the Democratic-Republicans, helping to win the national victory for his party. But when the votes were counted, an issue arose: Jefferson and Burr had tied with 73 electoral votes each. At the time, presidential and vice-presidential candidates did not run on a shared ticket. Instead, whichever candidate got the most votes became president, while the runner-up became vice president. Many Democratic-Republicans expected Burr to concede the election to Jefferson, the party's intended candidate. When he stayed silent, the decision was left to the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives.

This must have left Burr feeling confident in victory; Hamilton and Jefferson were known to be bitter rivals, leaving him to hope that Hamilton would use his influence in the Federalist Party to defeat Jefferson. He was mistaken. Hamilton may have disagreed with Jefferson, but he at least viewed him as a man of principle. By contrast, Hamilton believed Burr to be a selfish man who held nothing dear. He told correspondents that Burr was "daring enough to attempt anything – wicked enough to scruple nothing" (quoted in Wood, 284). In short, while Hamilton held Jefferson in contempt, he still preferred him over Burr and urged his followers to support Jefferson as president for the 'public good' of the nation. Thus, with Hamilton's intervention, the House of Representatives handed the presidency to Jefferson, with Burr becoming vice president.

Because of Burr's behavior during the deadlock, Jefferson did not trust his new vice president. He did not ask Burr's opinion when appointing members of the cabinet and barely invited Burr to attend cabinet meetings at all. It did not take Burr long to realize that he was being squeezed out of Jefferson's inner circle. He began supporting Federalist policies out of spite and, in 1802, attended a Federalist celebration of Washington's birthday, which scandalized Democratic-Republican leaders. The breaking point came in November 1804, when Burr presided over the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase in the US Senate.

Hoping to rid the judiciary of Federalist influence, Jefferson had moved to impeach Chase, an associate justice on the US Supreme Court and an ardent Federalist. Chase was accused of conducting unfair trials under the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), and his impeachment was duly confirmed in the House of Representatives, before being handed off to the Senate. Although Burr was under tremendous pressure to convict, he was determined to remain impartial; he was praised for this conduct, with one newspaper writing that he "conducted [the hearings] with the dignity and impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil" (battlefields.org). In the end, Chase was acquitted, but Burr's impartiality cost him his position, as an enraged Jefferson made it clear that he would be picking a new running mate in the next election.

Hamilton Duel & Treason Trial

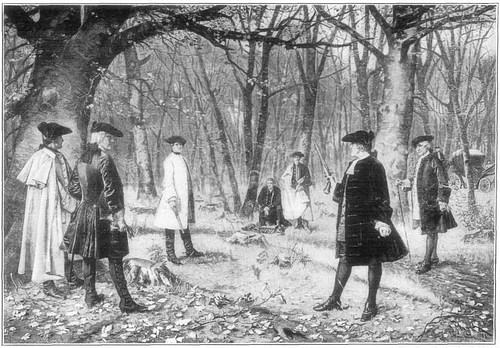

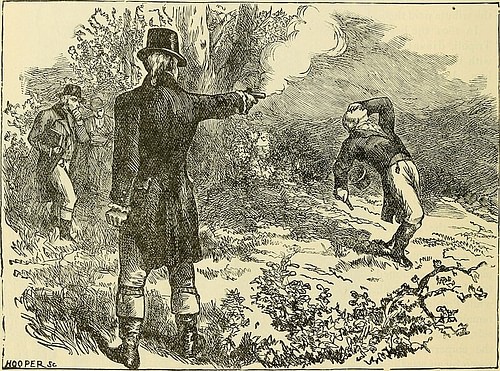

Even before the impeachment trial, Burr had suspected he was going to be replaced as Jefferson's vice president in the 1804 election. He knew he would need to seek another job, and after examining his options, he decided to run for governor of New York. While he still enjoyed much support in New York, especially from the Livingston and Clinton families, Burr found that his ambitions were to be frustrated by an old rival. Once again, Alexander Hamilton vigorously opposed Burr's candidacy, privately remarking to friends that the vice president was "a dangerous man and one who ought not be trusted" (quoted in Chernow, 680). Burr was defeated in the gubernatorial election, leaving him in an angry and vindictive mood. When, on 18 June 1804, he learned of Hamilton's remarks, he blamed him for his loss and demanded "a general disavowal of any intention on the part of General Hamilton in his various conversations to convey impressions derogatory to the honor of M. Burr" (quoted in Wood, 384). When Hamilton refused to disavow anything, Burr challenged him to a duel.

The two parties met at Weehawken, New Jersey, at 7 a.m. on 11 July 1804. The details about what happened next are still murky – there is disagreement about whether Hamilton intentionally wasted his shot or being struck by a bullet caused him to overshoot. In any case, Hamilton missed, while Burr's shot hit Hamilton just above his right hip; the wound was mortal, and Hamilton died the next day. The country mourned for Hamilton, and Burr was villainized in the press; one Maryland newspaper accused him of premeditated murder, while a New York paper called him a "base assassin" (quoted in Chernow, 716). He was charged with murder in New York and New Jersey, where dueling was illegal, although these charges were eventually dropped. The duel effectively ended Burr's career and turned him into a political outcast; he had already burned his bridges with the Democratic-Republicans, and now had killed the Federalists' leader, ending any goodwill he had left with them.

So, when his term as vice president expired in March 1805, Burr went west, moving into the virgin lands of the Louisiana Purchase. He had leased 40,000 acres of land in modern-day Louisiana and began to gather support for a settlement there. His main contact was General James Wilkinson, governor of the Louisiana Territory, with whom he conferred about the Spanish in Mexico; at the time, Spain and the United States were engaged in a border dispute. In the summer of 1806, Burr led 80 men down the Mississippi River in flat-bottom boats toward New Orleans. President Jefferson, meanwhile, received reports of this and quickly became suspicious. It was rumored that Burr planned to lead an invasion of Mexico or Texas, incite a revolution in Mexico against Spanish authority, or, even worse, that he intended to form a new nation in the West and secede from the Union. General Wilkinson, worried about being caught up in a scandal, decided to save himself by betraying Burr, warning Jefferson of a "deep, dark, and widespread conspiracy" (quoted in Wood, 384). Wilkinson gave Jefferson ciphered correspondence supposedly written by Burr detailing his plans.

Jefferson issued a warrant for Burr's arrest. The former vice president surrendered to authorities in January 1807 but, after being paroled, fled into the wilderness. He was recaptured in February and escorted to Richmond, Virginia, where he was accused of treason and tried before the US Fifth Circuit Court, with Chief Justice John Marshall presiding. Jefferson worked hard to secure a conviction, producing all the letters and evidence at his disposal. However, the case against Burr was significantly weakened when it was revealed that the ciphered letter had been heavily doctored by Wilkinson, who had hoped to minimize his own misconduct by using Burr as a scapegoat. Ultimately, Burr was acquitted; under the definition of 'treason' adopted by Marshall for the trial, one needed to commit an act of war to be convicted, which it could not be proven that Burr had done. Immediately after the trial, effigies of Burr and Marshall were hung by angry mobs. Burr went into self-imposed exile and fled to England in 1808.

Later Years & Death

While in exile, Burr continued to look for ways to revive his career. He spent the next several years petitioning European governments to support his plan for an invasion of Mexico but was rebuffed each time. He was eventually kicked out of England and was refused an audience with French Emperor Napoleon I. In 1812, Burr returned to the United States, penniless and deeply in debt. He went to New York City where he quietly practiced law, using his mother's maiden name 'Edwards' to avoid his creditors. The killing of Hamilton always hung over him like a shadow, villainizing him in the eyes of his contemporaries. For most of his life, Burr refused to show any remorse for the duel, aside from one moment when he apparently remarked, "Had I read Sterne more and Voltaire less, I should have known that the world was wide enough for Hamilton and me" (quoted in Chernow, 722).

Burr's wife, Theodosia, had died in 1794. His daughter, Theodosia Burr Alston, was lost at sea in early January 1813, when the ship she was aboard, the Patriot, mysteriously disappeared. Despite these tragedies, Burr was not entirely devoid of family in his old age. He had several illegitimate children, had adopted two sons, and had raised the children from his wife's first marriage as if they were his own. In 1833, Burr married socialite Eliza Jumel, but their marriage was brief; Jumel sought a divorce after Burr wasted her fortune on failed land speculation ventures. In 1834, Burr suffered a serious stroke and died on Staten Island two years later, on 14 September 1836.