Abu Bakr (l. 573-634 CE, r. 632-634 CE) was an early convert of Islam; he was a close friend and confidant of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and became the first caliph of the Islamic empire – a successor to Muhammad's temporal position but not a prophet himself, as according to Islamic sources, that had ended with Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE). He helped his friend Muhammad through thick and thin in his mission and stayed by his side until the end of his days. After the death of the Prophet, he became the first of the four caliphs of the Rashidun Caliphate – as it is called by Sunni Muslims. In his brief reign of two years, he reunited the Arabian Peninsula and started conquests in Syria and Iraq, which were later carried on successfully by his successors until 656 CE when the first Islamic civil war, the First Fitna (656-661 CE) erupted and expansion was temporarily halted. It was also during Abu Bakr's reign that the revelations dictated by Muhammad were compiled in the form of the Islamic holy scripture: the Quran.

Early Life

Abu Bakr Abdullah ibn Uthman was the son of Uthman Abu Quhafa (l. 538-635 CE) of the Banu Taym clan of the Quraysh tribe; he was born in Mecca in 573 CE. His real name was Abdullah, meaning servant of Allah (God); Abu Bakr was a nickname given to him due to his love for camels, it means “father of a camel's calf”, but the latter name caught on and he is mostly referred to by it. He belonged to a rich merchant family, and was well educated; he had a sharp memory and a fondness for poetry, which was one of the quintessential traits of Arabian gentlemen.

Conversion to Islam & Companionship of the Prophet

When Muhammad started preaching Islam in 610 CE, Abu Bakr, who was a close friend of his, became the first male convert (the earliest convert was Khadija, the Prophet's wife), although some historians suggest that he was not the first one but one of the earliest ones. Nevertheless, he was one of the most supportive allies of Muhammad, not only did he help the Prophet financially but he also persuaded many of his friends and colleagues (his family as well) to accept the new faith. Abu Bakr's utmost and sincere support for the Prophet earned him the nickname of Siddique (trustworthy).

However, even Abu Bakr's wealth and reputation could not save Muhammad and his small group of followers from Meccan atrocities, and Abu Bakr himself was not immune to them either. Nevertheless, he did not inch back from the new faith, in fact, he is said to have paid for the freedom of several slaves who had accepted Islam, such as an Ethiopian named Bilal. The death of the Prophet's influential uncle Abu Talib in 619 CE left the tiny band of Muslims more vulnerable than ever. At this pivotal moment (622 CE), invitations came from Yathrib (future Medina) for the Prophet and his companions to come over; the Prophet was offered kingship of the city. The Muslims were only too happy to oblige, they migrated in batches to the city, but Abu Bakr stayed behind with his friend (whom the Meccans had now resolved to kill), and the duo left Mecca together with the Meccans in hot pursuit. They took refuge in a cave of a mountain named Jabal Thaur (Mount Bull), where they were able to evade the Meccans, who then gave up and retreated.

Once in Medina, Abu Bakr continued to support Muhammad and became one of his advisors in matters of the state. He also participated in major battles with the Meccans such as Badr (624 CE) and Uhud (625 CE). Abu Bakr also tied his daughter Aisha (l. c. 613-678 CE) to the Prophet in wedlock to cement his affiliation with him, as was the norm back then, and hence became his father-in-law. He also led the congregational prayers in the Masjid an-Nabwi (Mosque of the Prophet) during the last days of the Prophet, when the latter was ill.

After the Death of the Prophet

When Prophet Muhammad died in 632 CE, the Muslim community was in a state of shock. Some even refused to believe that he was gone. Had it not been for his careful warnings, people might have venerated him as a divine figure, but he had made it quite clear that he too was a human and bound by laws of nature. Still, people had a hard time coping with the fact that they will not be guided by divine revelation (as Muhammad had claimed that he received them from God, and no one else could). Abu Bakr rallied the community, he is said to have addressed them, according to Syed Ameer Ali in A Short History of the Saracens, by saying:

Mussulmans (Muslims), if you adored Muhammad, know that Muhammad is dead; if it is God that you adore, know that He liveth, He never dies. Forget not this verse of the Koran (Quran), 'Muhammad is only a man charged with a mission; before him there have been men who received the heavenly mission and died;' – nor this verse. 'Thou too, Muhammad, shalt die as others have died before thee.' (20)

Another problem, a more practical one, was that Muhammad had made no clear indication as to who should succeed him nor did he even hint what type of government should prevail after his death. Of the many followers of Abu Bakr, one notable man from the Banu Adi clan was Umar ibn al-Khattab (l. 584-644 CE). Umar too was an early convert and perhaps one of the most daring people in the whole community, he had a reputation for being strict and steadfast. With Umar's support, Abu Bakr became the successor to Muhammad's realm; he adopted the title Khalifa'tul Rasul (the vicegerent of the Prophet) – shortened to Khalifa (Caliph), hence the basis of Islamic Caliphates was laid down by him. His claim was not uncontested; although different versions of events are quoted by various historians, the gist is the same: many held the view that only Ali ibn abi-Talib (l. 601-661 CE), a son-in-law of the Prophet, and also a blood relative, held the right to inherit his realm. Ali's own involvement in pushing forward this claim is highly debated, though; but what is clear that his supporters, who came to be known as Shia Muslims or Shia't Ali (party of Ali) saw Abu Bakr as a usurper, and regardless of his achievements, they deny the authenticity of his claim as a caliph.

First Caliph of Islam

Abu Bakr's first action as caliph was to dispatch an expeditionary force into Syria to avenge the defeat of the Battle of Mu'tah (629 CE), as had been planned by the Prophet (this force was not very successful though, later forays achieved much more). This meant to show not only that the Muslims had not forgotten their fallen comrades but also to declare that the Caliphate would continue what Muhammad had started.

But another issue arose in the deserts to the east of Medina: the Bedouin tribes that had accepted Islam less due to spiritual motivation and more for political reasons now renounced their support for the new faith. They claimed that their covenant ended with the death of Muhammad, they even refused to offer zakat (alms to be paid in Islam) to Medina. To make matters worse, many imposter prophets appeared in various tribes; the most notable one, Musaylimah (d. Dec 632 CE, referred to as the Arch Liar by Muslims), had started his activities in the last years of Muhammad, and as Muhammad predicted many would follow his example. Abu Bakr could not let the Arabs fragment away from his master's realm, let alone allow them to mold and twist his faith into different versions.

Just as at the time of Muhammad, Medina stood as the bastion of Islam (supported by Mecca this time though) against the hordes of rebellious Arabs. Had Abu Bakr lacked leadership skills, he might not have stood up for the enormous undertaking, but as he was about to show, he was more than competent for his position. After he secured Medina from incursions from these apostates, he declared jihad (holy war – contextually) against the traitors.

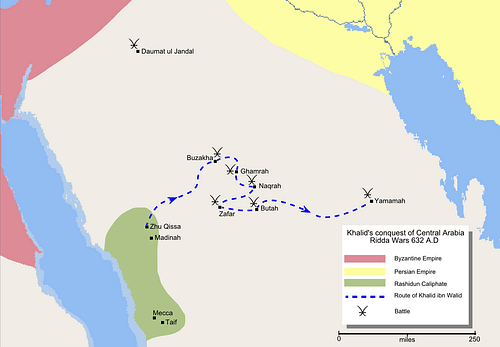

Ridda Wars

He summoned all able-bodied men of the faith under the banner of Islam. He used the momentary disunity amongst the various rebellious tribes to subjugate them one by one. These wars were later stylized as the Ridda Wars or the Wars of Apostasy (632-633 CE). By the end of the first year of his reign, Abu Bakr had reunited the whole of the Arabian Peninsula and, though the use of the sword was not spared on the battlefield, he made no attempt to punish his enemies after they had surrendered.

Musaylimah was killed in the Battle of Yamama (Dec 632 CE) by an army led by Khalid ibn al-Walid (l. 585-642 CE), who despite many controversies against him was the ablest and most loyal general that Abu Bakr had, which provided him full immunity from the Caliph against many who wished to see him dead (most notably Umar). Though outnumbered vastly on the eve of the aforementioned decisive battle, Khalid showed his worth as a commander, he had not lost a single battle before and had no intention of losing that day. He was all too familiar with the fickle-minded nature of desert fighters and how much importance they laid on people rather than their cause, so when Musaylimah fell fighting, his supporters were immediately routed.

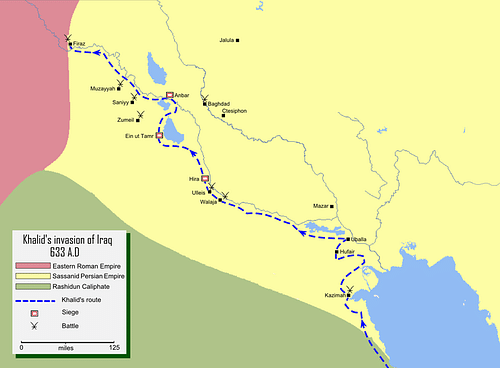

Invasion of Iraq & Syria

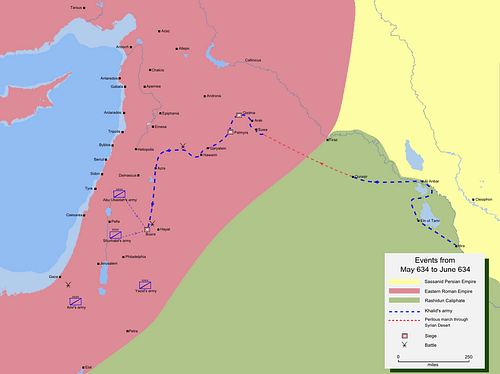

Abu Bakr, following in the footsteps of Muhammad, decided to direct the nascent energies of Arabian warriors to the neighboring lands of Syria (under the Byzantines) and Iraq (under the Sassanian Empire). The two superpowers had not only exhausted their resources with their constant warfare but resentment amongst the populace had also reached unprecedented levels, and so when the Muslim armies appeared on their frontiers, the loyalists of empires scurried for their lives while the Monophysites and Nestorians of the Byzantine Empire and the non-Zoroastrian Arabs in Iraq willingly accepted their new lords. Khalid was sent to Iraq (633 CE), where he was joined by a powerful Arab lord who helped him take the Iraqi city of Hira.

Though successful and well-disciplined on the battlefield, Khalid disobeyed his caliph's clear orders by rather brutally executing Sassanian prisoners of war. In the meanwhile, in Syria, the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE), a warrior-spirited sovereign, prepared for an effective counterattack. Since he could not lead his army himself owing to his ailment, he put his brother Theodore in charge. Sensing correctly an impending counter-offensive and being familiar with Byzantine warfare, Abu Bakr took no risk and ordered Khalid to leave Iraq and move to Syria – for only his military skills could match that of his foes.

Khalid moved across the trackless and waterless desert to Syria with all but a few handpicked men and some camels to use as water reservoirs; a devastating example of coordinated Arab mobility. After raiding Syrian territories, he rallied the Muslim armies in the area and faced the Byzantines in the Battle of Ajnadayn (634 CE), which was a decisive Rashidun victory and further strengthened their position in the region. However, in the absence of Khalid, the Sassanians had dealt a severe blow to the Arab troops in Iraq, knocking them off their gains.

Abu Bakr's greatest strength was perhaps his cool-minded and resolute nature, instead of being driven by emotion, as most Arabs were, he preferred to adopt a more rational approach to matters, as evidenced by his support for Khalid. Although the general was not a paragon of virtue, Abu Bakr realized before most others that he was an irreplaceable asset.

Compilation of the Quran

Abu Bakr also safeguarded the revelations dictated by Prophet Muhammad in the form of the Quran; an undertaking he was reluctant to commit to since the Prophet had not done so himself. Umar, however, pointed out the number of companions of the Prophet who had died at Yamama, and foreseeing a time when none remained to remember the Quran by heart, he warned Abu Bakr of the possibility that the revelations (which had been written in isolated forms) be subjected to change – which Abu Bakr could never let happen. Hence he was forced to comply with Umar's request and ultimately preserved the revelations dictated by Muhammad for over two billion of his followers to read today.

Abu Bakr ordered that all of the written revelations be gathered alongside those companions of the Prophet who had remembered the Quran by heart. Then he gave the duty to a trusted scribe of the Prophet, a man named Zaid ibn Thabit (l. c. 610-660 CE) to compile it in the same sequence as had been instructed by the Prophet; since the revelations were not revealed in order but Muhammad had informed his followers of the exact sequence. Extreme care was taken that not even a single word of the Holy Scripture was changed (even if the gist remained the same), as in the eyes of the Muslims that would have been a great sin. After his death, the copy was given to Hafsa (l. c. 605-665 CE), a daughter of Umar and a widow of the Prophet, for safekeeping.

Death & Legacy

Abu Bakr did not live long enough to hear the tidings of the success at Ajnadayn and the minor setback in Iraq, for he died of natural causes in 634 CE. Before departing this world, he nominated Umar ibn al-Khattab, his strongest and most able supporter as his successor, who would reinforce Muslim troops in Iraq and order further expansion in Syria. Umar would carry on the same parameters of leadership, which would allow him to further expand the dominions of Islam.

Whether Abu Bakr was a usurper or whether his claim was legitimate, he did achieve a great deal. Not only did he prevent the fragmentation of Muhammad's empire, which would have meant the extinction of Islam altogether, he ordered successful campaigns to Iraq and Syria, committed the Quran to writing, and he was also the first of the many to come to be called the Caliphs of Islam.