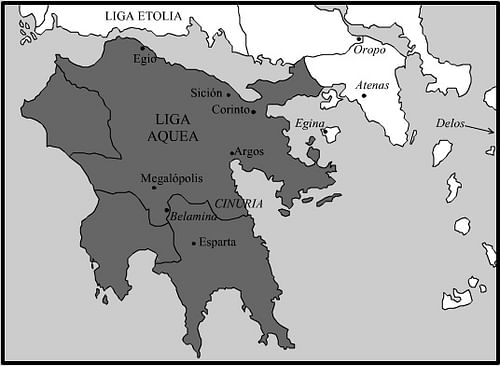

The Achaean League (or Achaian Confederacy) was a federation of Greek city-states in the north and central parts of the Peloponnese in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. With a combined political representation and land army, the successful early years of the League would eventually bring it into conflict with other regional powers Sparta, Macedon, and then later Rome. Defeat by the latter in 146 BCE brought the confederacy to a dramatic end.

Founding & Membership

The League was formed in c. 281 BCE by 12 city-states in the region of Achaea who considered themselves as having a common identity (ethnos). Indeed, several of these states had already been members of a federation (koinon) in the Classical period but this had broken up c. 324 BCE. The principal founding members of the League were, then, Dyme, Patrai, Pharai, and Tritaia, all located in western Achaea in the northern Peloponnese of Greece. More Achaean cities joined in the following decade and the stature of the League grew when Sicyon, a city outside the region, joined in 251 BCE. From then on, membership steadily grew to encompass the whole of the Peloponnese.

Members enjoyed the strength in numbers of the League whilst maintaining their independence. Their primary obligation was to contribute a quota of warriors for the League's collective army. Cities also sent representatives to meetings of the League in proportion to their status - smaller cities sent one, and larger ones could send three. Of these, the original founding and larger members continued to exert more influence and their representatives certainly carried more stature as regional statesmen. The representatives met, perhaps four times each year, on a federal council and there was also a citizen's assembly. Up to c. 189 BCE meetings were held at the sanctuary of Zeus Homarios at Aigion and thereafter at individual city-states, presumably on a rotation basis.

The representatives sent by city-states were led by the strategos (general), a position which was introduced in c. 255 BCE and held for one year. To better ensure one state did not overly dominate, the position could not be held for consecutive years. However, this did not stop some notable figures such as Philopoimen (from Megalopolis) and Aratos (from Sicyon) holding the position several times in their careers. Other important positions included the cavalry commander (hipparch), ten damiourgoi officials, and a League secretary.

The League not only gave its members a better defence against outside aggression but also brought several non-military benefits such as access to a common judicial process and the use of a common currency and system of measurements.

Successes

As the League expanded and became more influential, so too its relations with other regional powers increased in intensity. Local rivalries existed in particular with Sparta to the south and the Aitolian League across the straits of Corinth. Even distant Macedon and Egypt began to take an interest in the League's affairs. These relations became ever more strained as the League became more ambitious. In 243 BCE Corinth was attacked and forcibly made a member of the League. The effect of this acquisition was to weaken the Macedonian presence in the region and so allowed the League to assume more member cities, notably Megalopolis in 235 BCE.

The Macedonian Wars

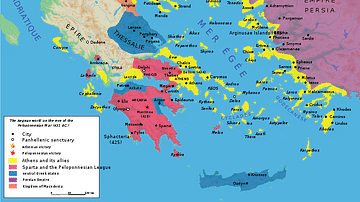

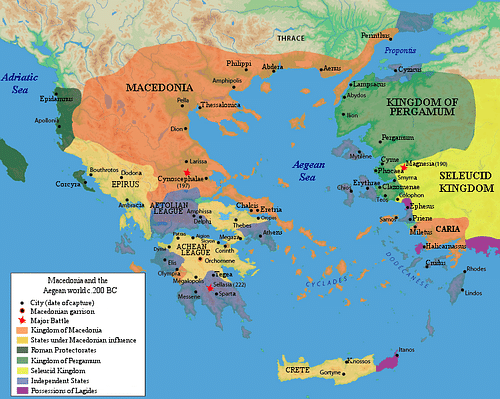

Trouble was brewing, though, as Cleomenes III of Sparta (r. 235-222 BCE) sought to expand his own influence in the region. This forced the League to seek help from Antigonos III of Macedon. Together the two allies defeated Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BCE. As payment for their support, the acropolis of Corinth, the Acrocorinth, was given back to the Macedonians.

Then a new heavyweight power entered the scene of Greek inter-state politics: Rome. The League remained loyal to Macedon in the First Macedonian War (212-205 BCE) between the two powers. This was an unwise move as Philip V's Macedonian army was defeated. The Achaeans then pragmatically switched sides in the Second Macedonian War (200-196 BCE) and supported Rome. This time finding itself on the winning side, the League had to carefully balance its ambitions with the new wider political situation. Around 196 BCE Rome and the League signed a treaty of alliance, quite a distinction at the time.

Conflict with Rome & Collapse

Sparta, Elis, and Messene were made members of the League while Rome was distracted by another war, this time against Antiochos III, the Seleucid king. Again the Romans were unstoppable and their defeat of Antiochos at Thermopylae in 191 BCE and Magnesia in Asia Minor in 190 BCE left Greece ever more vulnerable to Roman dominance. A Third Macedonian War (171-167 BCE) brought another Roman victory and Greece was well on the road to become nothing more than a Roman province.

Already not best pleased by the League's acquisition of Sparta, Rome became suspicious of its ambiguous political stance. As a consequence, Rome took 1,000 prominent Achaean hostages back to the Eternal City and in 146 BCE there was open war between the two powers in what is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War. Predictably, the Roman war machine prevailed again; Corinth was sacked and the League in its current form disbanded. The confederacy was, though, later permitted to function in a more limited way and on a more local basis. It survived as such into the 3rd century CE and perhaps beyond, occasionally forming alliances with other such groups within the Greek region of the Roman Empire.