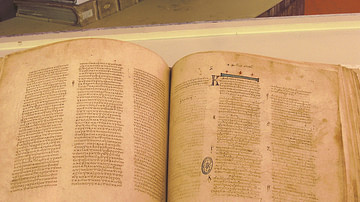

The Acts of the Apostles is the story of how the movement that became Christianity began in Jerusalem and spread throughout the Eastern Mediterranean cities of the Roman Empire. It was written by the same author as the third gospel, assigned to Luke, sometime between c. 95 and 120 CE. The combined work, known as Luke-Acts to scholars, is the longest text in the New Testament.

Purpose

The Jewish prophets had predicted that the God of Israel would intervene in human history one final time and institute his kingdom on earth. God would raise up a messiah figure to lead the people and restore the nation of Israel according to God's original plan in the Garden of Eden. The kingdom would include some Gentiles (the nations, pagans) who repented and worshipped God.

According to the gospels, Jesus Christ declared that the kingdom was imminent. But decades had passed, and there were no indications of the kingdom. The purpose of Acts was to demonstrate that everything the prophets had predicted was, in fact, being manifest in the contemporary actions of the first Christian missionaries, the disciples and Paul. As a sequel, the events in Acts also 'fulfilled' the predictions of Jesus in Luke's gospel.

The sources for Acts are the Jewish scriptures, the books of the prophets, and travelogues of the journeys of Paul the Apostle. Luke included specific details found in the letters of Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles, but there are also contradictions. When in doubt, we take Paul's letters as the more credible source. Paul's letters contain no internal dates. Scholars use Acts to establish a chronology of Paul's travels and letters.

Acts (praxeis apostolon in Greek) is characterized as ancient historiography, the method of writing a history of a people and events. Historiographers were expected to create speeches for famous characters that matched their known characteristics. Acts contains 24 major speeches, with the consensus that Luke was the author.

The Structure of Acts

Both the Gospel of Luke and Acts open with a dedication of a believer named Theophilus. Then Acts continues with Jesus teaching the disciples for 40 days before ascending to Heaven. The disciples ask him if he would then restore the kingdom of Israel, and he says:

"It is not for you to know the times or dates the father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the holy spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth." After he said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight.

(Acts 1:7-9)

The opening is essentially the table of contents for Acts. Acts relates stories of Peter and John witnessing in Jerusalem and Judea, the mission in Samaria, ending with Paul in Rome, "the ends of the earth." This is the basis for the theory that Acts was written in Rome, but it remains debatable. As in his gospel, Luke's 'proof' was aligning each event with historical figures. As he had Paul say, these events were "not done in a corner" (Acts 26:26), but were being actualized on the stage of history. Acts names historical Jewish kings and Roman magistrates.

Pentecost (Acts 2)

Pentecost was an ancient Jewish religious festival known as Shavuot (Hebrew for "weeks"); one of three pilgrimage festivals commanded in the Jewish Scriptures. In Luke's story of John the Baptist, he had John predict that the messiah would baptize people with the holy spirit and fire (Luke 3:16).

When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability. Now there were devout Jews from every people under heaven living in Jerusalem. And at this sound the crowd gathered and was bewildered, because each one heard them speaking in the native language of each. Amazed and astonished, they asked, "Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language?"

(Acts 2:1-8)

The phenomenon of "the tongues" became the concept of "glossolalia" (practiced by modern Pentecostal denominations). When a person was possessed (taken over) by a god or spirit, they went into a trance and uttered things in an unknown language. The key to the miracle of tongues is in relation to the other nations. "Tongues" in the Greek here refers to "languages." The disciples were "Galileans," who spoke Aramaic. The Jews from other lands heard them in their own languages.

This possession of the spirit became combined with one of the first Christian rituals, that of baptism. The way in which the spirit was manifest in the early communities was by experiencing a literal, physical miracle in the ability to "speak in tongues," prophesize, heal, and raise people from the dead, all evident in Paul's letters.

Peter & John

The disciples Peter and John continued to pray at the Temple every day. Peter cured a cripple and many of the crowd became believers. The high priest and the Sadducees ordered them to stop. But when they continued, they were arrested and put in jail. Through the night, an angel of the Lord miraculously released them. This established the prototype for the persecution of early believers by Jews through the rest of Acts, always followed by divine deliverance.

Stephen

Acts contains our earliest evidence of hierarchy in the communities of early Christianity, with the election of deacons to take care of practical matters in the distribution of food and clothing to the poor. One of them, Stephen, was then arrested for allegedly speaking against the Temple. Stephen's speech highlighted the many times that the Jews had disobeyed God. Convicted by the Sanhedrin, he was stoned to death (the punishment for blasphemy). Right before dying, he had a vision: "Look, ... I see the heavens opened and the son of man standing at the right hand of God!" (Acts 7:56). In the ancient world, deathbed speeches were often taken as revelations from the gods. The narrative function of Stephen's story was to verify that Jesus was now in heaven.

Paul

Luke wrote that Paul was present at the stoning of Stephen: "That day a severe persecution began against the church in Jerusalem, and all except the apostles were scattered throughout the countryside of Judea and Samaria" (Acts 8:1). Paul persecuted the early believers by having them arrested and voting for the death penalty. He went to the high priest and obtained arrest warrants for the believers in Damascus.

One of the most familiar stories from Acts is that of Paul on the road to Damascus:

... as he was ... approaching Damascus, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?" He asked, "Who are you, Lord?" The reply came, "I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do."

(Acts 9:3-6)

Blinded, Paul was cured by a believer in Damascus (for both his physical and spiritual blindness) and baptized.

There are historical difficulties with Luke's story of Paul:

- In his letters, Paul admitted that he initially persecuted the church of Christ, but never said why or how.

- Why would the apostles be permitted to stay in Jerusalem, while other believers were scattered?

- Luke never provided a rationalization for why the early believers should receive the death penalty. Claiming that someone was the messiah did not violate the Law of Moses.

- It is improbable that the high priest had any authority to issue an arrest warrant in another city (a function only for Roman magistrates).

The narrative function of this story is to explain the movement beyond Jerusalem.

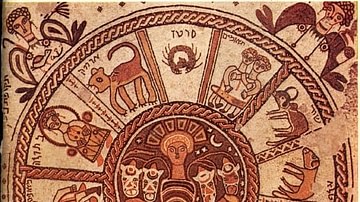

God-fearers & Peter

"God-fearers" (Gentiles who respected and venerated the God of Israel), were an important group for Luke. With his descriptive adjectives ("devout," "pious"), these people have taken that first step; they have turned to the God of Israel. Synagogues in the cities of the Roman Empire were not sacred spaces; there was no bar for Gentiles attending synagogue services or activities. Many Gentiles admired Jewish teachings. It is among the God-fearers in the synagogues that Gentiles most likely first heard the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

The historical evidence for God-fearers was discovered in the archaeological ruins of a synagogue in Aphrodisias (Turkey). An inscribed pillar listed the names of donors to the building. Many of them were Greeks, described as God-fearers, who also left their names on public libraries and other buildings.

God-fearers first appear in an elaborate story of Peter and Cornelius, a God-fearer, who was a centurion of an Italian cohort. Peter and Cornelius had simultaneous visions and Peter then baptized all of Cornelius' household. In Peter's summation in Acts 15.9, "in cleansing (or purifying) their hearts by faith he has made no distinction between them and us."

The Apostolic Council

Between Acts 10 and Acts 15, we see the geographical progress of the mission, but now with some unexpected interest in Antioch, as the missionaries prior to this time spoke only to the Jews: "... some men of Cyprus and Cyrene ... spoke to the Hellenists also [pagans], proclaiming the Lord Jesus ... a great number became believers and turned to the Lord" (Acts 11.20-21).

In Acts 15:1, "certain individuals came down from Judea and were teaching the brothers, 'Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.'" Luke provided no rationale for why some of the believing Pharisees required full conversion through circumcision. The prophets did not require full conversion of Gentile believers. A meeting was called for participants in Jerusalem. This became the first Apostolic Council, followed by many more councils over the next few centuries.

James, the brother of Jesus, made the decision:

Therefore I have reached the decision that we should not trouble those gentiles who are turning to God, but we should write to them to abstain only from things polluted by idols and from sexual immorality and from whatever has been strangled and from blood. For in every city, for generations past, Moses has had those who proclaim him, for he has been read aloud every Sabbath in the synagogues.

(Acts 15:19-21)

Food "polluted by idols" in the 1st century CE recognized the problem that meat in the public markets came from the leftover sacrifices in the temples. During religious festivals in the cities, the leftovers were distributed to the community. "Things polluted by idols" was a Jewish disdain for this meat. Jewish communities often had their own butchers because of this taint of idolatry. Jews also had a law that the blood of animals had to be drained before sale and use.

"Sexual immorality" (pornea) has several connotations in the scriptures: Jewish incest codes, but also unchastity, adultery, and prostitution. Illicit sexual unions became incorporated into Jewish vice lists against the nations, often repeated in Paul's letters. Drawn from the purity/impurity rituals and concepts of Leviticus, which were only viable at the Temple in Jerusalem, Acts was written after the destruction of the Temple. But the dictates of Acts 15 could be accomplished by the Gentile believers in everyday life.

Luke's Apologia to Rome

The literary device of an apologia, apology, was an explanation. In consolidating Roman power in his wars in the East, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) utilized Jewish mercenaries in the Roman army. Returning to Rome, Caesar enacted legislation in the Roman Senate that rewarded Jews with the privilege of continuing to practice their ancestral customs, exempt from the state cults of Rome. Inherent in his legislation was that Jews were to follow Roman law and not to recruit beyond the synagogues nor interfere with the customs of Rome. To do so was construed as treason.

Between 66-73 CE, the Jews led a revolt against the Roman Empire. We know about this period because the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE) wrote about what led to the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE in his Antiquities of the Jews. The decades of the 40s, 50s, and 60s experienced civil disturbances between Jews and Greeks in various cities. In Luke's description of Paul's travels, he never included any of these details. The kingdom of God in Acts is always in reference to the eschatological, proleptic kingdom, predicted by the prophets, and never as a political challenge to Rome. In the gospels and Acts, the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth was blamed on oppositional Jews.

Luke did not include the negative elements of idolatry from the prophets. In his letters, Paul did preach against traditional idolatry: "Therefore, my beloved, flee from idolatry" (1 Corinthians 10:14). But no speech by Paul in Acts reviled the gods. What the speeches in Acts emphasized was that "these worthless things" (such as ignorant sacrifices to the gods in Lystra in Acts 14:15) would not result in Luke's concept of salvation, the forgiveness of sins.

Rejection & Innocence in Acts

Luke applied the typology of rejection from the traditions of the prophets. Initially, the prophets of God were well-received and honored until they began the message of impending doom and destruction for the sins of the people. By the 1st century CE, there were legends that the prophets of Israel had all died as martyrs. Luke's stories of Paul in the various cities portrayed him as a traditional prophet with his many ordeals and sufferings.

Luke created a repeated pattern of Paul's reception/rejection in the synagogues and cities. In each city, Paul went to a synagogue first to proclaim the good news, which was initially received well. When he returned the next day, reaction began, followed by tension, persecution, and ultimately expulsion from the synagogue. Any civil disturbances that overflowed were initiated by Jewish disbelievers. Paul then declared that he would "go to the Gentiles," from now on. Next city, same pattern of synagogue first, then expulsion.

In every city, it was the 'jealously of the Jews' behind civil disturbances that led to the arrests of Paul, and not any preaching against idolatry: "when the Jews saw the crowds, they were filled with jealousy" (Acts 13:45). What were the Jews jealous of? The Greek zilia meant resentment toward someone deemed superior, but with the mention of "the crowds," jealousy became the idea that Christians were attracting more pagan converts than Jews. But Judaism was not a missionary religion.

Each time Paul was arrested and imprisoned, the local governor or city magistrate always found him innocent of any civil disturbance. Acts 18 describes a trial before Gallio, the proconsul in Corinth; the Jews of the city had charged him with "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law" (18:13). In this case, the laws of Rome. Here, and in front of all other magistrates, Paul is declared innocent in relation to the Julian legislation. Rather, all problems with the new movement were 'in-house' differences among Jews.

Luke claimed that Paul was a Roman citizen (although not mentioned by Paul in his letters). The privilege of Roman citizenship was due process, the right of appeal, all the way up to the emperor. This was the vehicle for getting Paul to Rome ("the ends of the earth"). When Paul arrived in Italy he was put under house arrest, awaiting his appeal. Nevertheless, Paul was free to continue his mission:

He lived there two whole years at his own expense and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance.

(Acts 28: 30-31).

In other words, even at the heart of the Empire, Paul was not charged with teaching against the traditions of Rome.

Given the prominence of Peter, James, and Paul, Luke did not report their deaths in Acts. It is only in the later stories in the 2nd century CE that described the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul during the reign of Nero (r. 54-68 CE). This remains a conundrum, but it is significant that there is no mention of persecution or execution by Rome in Acts.

The Legacy of the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles remains vitally important as the first Christian history. Acts provides a wealth of information on the variety of Jewish, Gentile, and pagan beliefs and practices in the 1st century CE. Unfortunately, Luke's polemic in the stories of the persecution of believers by the Jews was enhanced in the 2nd century CE. After the separation of Christianity from Judaism, Church Fathers used this for their creation of Adversos Literature, Jews as "adversaries," the enemy of Christians. Acts became the proof-text for the claim that just as they did in the 1st century CE, Jews were continuing to persecute Christians in the Roman Empire.