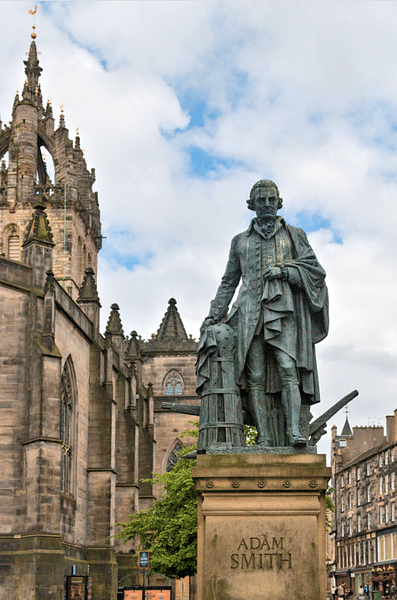

Adam Smith (1723-1790) was a Scottish philosopher, economist, and leading Enlightenment figure. In The Wealth of Nations, he advocates free trade and limited interference in markets by governments, for which he is seen as the founder of liberal economics. Regarded incorrectly as a champion of laissez-faire economics, Smith supported state intervention in important areas like the education of workers.

Early Life

Adam Smith was born into a landowning family living in Kirkcaldy, located to the north of Edinburgh across the Firth of Forth in Scotland, c. 5 June 1723. Smith's father, also called Adam, worked as a customs official while his mother, Margaret Douglas, did not need to work thanks to a significant land inheritance. Smith studied literature at both the University of Glasgow and, thanks to winning a scholarship, at Balliol College, Oxford, from 1740. He left Oxford in 1746, and from 1748, he gave public lectures in Edinburgh with great success. In 1751, Smith was appointed the Professor of Logic at the University of Glasgow, and the next year, he became the Professor of Moral Philosophy, a position he held until 1764. Smith cultivated friendships with other Scottish philosophers, most notably David Hume (1711-1776), and men of business like the merchant Andrew Cochrane (1693-1777).

Moral Philosophy

Smith's first major work was The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759. Here, Smith presents his views on moral philosophy, which emphasise:

Stoic virtues, and in particular that of self command. Smith's man of perfect virtue "joins to the most perfect command of his own original and selfish feelings, the most exquisite sensibility both to the original and sympathetic feelings of others."

(Blackburn, 446)

This positive view of an individual's use of reason, restraint, and sympathy and empathy for others was encouraged by what Smith called an "inner person" or "impartial spectator" (what we might alternatively call the voice of one's conscience). This view greatly influenced how Smith saw the best political system working for the greater good of the state's economy. The work eventually attracted wider attention, and Smith was employed as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch. The position was well paid but meant Smith had to move to France in 1764, first to Toulouse and then to Paris. In between, he stayed in Geneva and met the French author and philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778). Smith was involved in more practical affairs, for a time acting as advisor to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1766. It seems probable that Smith was, therefore, partly responsible for the tax policies applied to the Thirteen Colonies in North America, policies which ultimately led to the American Revolutionary War after the colonists considered that they should not pay taxes without political representation.

Buccleuch's financial support of Smith – he gave him a pension equal to his salary as tutor – permitted him to leave his university post and dedicate himself entirely to political philosophy. For his greatest work, Smith returned home to Kirkcaldy in 1767, where he lived with his mother. In 1773, he moved to London.

The Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith's political philosophy is presented in his book Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (often simply called The Wealth of Nations), which was first published in 1776. As the full title suggests, Smith's intention was to systematically and objectively investigate the best political system that could provide a nation with the greatest economic success, much like contemporary scientists were trying to do in the fields of physics, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics during the Scientific Revolution. Smith is realistic, unsentimental, and optimistic in his determination to improve the human condition. He believes in progress and that humanity is currently in a fourth stage of existence, what he calls the age of commerce (the previous three, in order, were the age of hunters, shepherds, and agriculture). These stages were based on Smith's extensive studies in history and contemporary trade. Commerce, for Smith, is the inevitable concluding stage since humans are social and trade is a social activity. Further, a thriving economy is based on a complex web of interdependence between people of all kinds.

Smith proposed the labour theory of value based on this interconnectedness between humans in the world of trade. That is, he highlighted the difference between the use value and the exchange value of something. For example, an old record player might be very useful to its owner to listen to their vinyl collection, but if few other people want such an item, then it has little value in terms of exchanging it for something else (most obviously cash). The exchange value of an item is related to how many people want to own such a thing, how difficult it is to obtain, how much labour it will save the buyer if they own it, and how much labour and what kind of labour is required to produce it. Smith elaborates on his theory by stating that the value of a person's labour is based on several factors, such as scarcity of skills, difficulty and danger of the work, and the length of education required to do the work, amongst many other factors. The labour theory of value was further developed by other thinkers, notably Karl Marx (1818-1883).

Smith was also determined to show in his book that the Christian dislike of wealth, based on such biblical passages as "it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God" (Matthew 19:24), had no foundation in nature and no place in modern economics. Indeed, Smith argued that helping the rich get rich generally helped everyone in society since those who were not rich would strive to improve themselves in imitation of those whom they saw as successful.

A Free(ish) Market

Smith believed that the state should interfere in economic markets only when it is necessary to prevent a situation of unfair competition. Essentially, then, the state should leave the economy to itself since it would be guided by what he called the 'Invisible Hand' of the market, a system of perfect liberty where the economy is self-adjusting as it adapts to continuous changes in production and consumption based on people's self-interest (much like gravity dictates how planets move in space). This idea later developed into laissez-faire economics (literally "leave things alone"), where any and all barriers and interference that might impede trade and commerce are eliminated. This was something beyond what Smith himself proposed. Smith believed in free international trade and was against such common policies as protecting domestic industries using import duties in the face of cheap imports (mercantilism) since this protection might help that industry but not the economy as a whole. He explains his point of view with the following example:

By means of glasses, hot beds, and hot walls, very good grape can be raised in Scotland, and very good wine too can be made of them at about thirty times the expense for which at least equally good can be bought from foreign countries. Would it be a a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?

(Yolton, 136)

Smith points out two more arguments against protectionist economic policies. He states that such protection would only help an industry in which that nation is less skilled and remove possible funds from other industries where the nation is more skilled. Secondly, protectionist policies create discord between nations, which should be endeavouring to pursue international trade as smoothly as possible. Smith cites the abuses of power perpetrated by the British East India Company (EIC) as an example of what can happen when a state interferes in trade and awards, for example, a monopoly on certain goods or trade areas, as was the case with the EIC.

Despite Smith's modern association with laissez-faire economics, he was not actually in favour of a complete abandonment of the markets by the state. Indeed, he thought a truly free market was a practical impossibility anyway. He regarded the state as having a duty to assist people in times of need (famine, for example) and help victims of instances where the free market failed to provide them with the necessary intellectual tools to work, earn a living, and improve themselves. For example, Smith advocated the state raise taxes to pay for the education of the poor in certain instances, principally because he believed this would improve the range of labour skills they could offer the economy but also to help compensate for the mind-dulling work of those who operated machines all day. Education, too, can help the fight against superstition and the grip of religious institutions on people's minds, something Smith, as an enlightened thinker, wanted to loosen.

Criticisms

Critics of Smith's approach, which allows the rich to prosper without constraint, point out that if wealth is concentrated in the hands of the few then inevitably the political power of the many will diminish. Smith's 'Invisible Hand', as unfeeling as gravity, also ignores factors that might be considered important for people's opportunities to gain wealth, such as the individual's political, ideological, and social background. Other critics lamented the weakening of traditional institutions in such a free market approach and the absence of any moral considerations. Smith might well have argued that these criticisms are valid, but the system is what it is, just like gravity exists whether we like it or not. One can add some checks and balances, but the laws of economics follow the laws of nature. For example, prices will always follow the law of supply and demand. Economics was, for Smith, also a science, and so, too, it must follow laws, as the historian E. Cameron here explains:

Economic activities, like everything else, must be regulated by scientific laws, which could be discovered by rational investigation. As in the case of the law of gravity, understanding these laws would not allow people to do whatever they liked, but it would teach them how to attain the limits of the possible. As a science, economics was morally self-validating; there was no possibility of conflict between the pursuit of individual self-interest and the good of the community. Thanks to the Invisible Hand, the two are synonymous.

(277)

Smith pointed out that "the greatest and most important branch of commerce of every nation is that carried on between the inhabitants of the town and those of the country" (Yolton, 137). This position illustrates that Smith's considerations of a nation's economy are being applied to the still largely pre-industrialised Britain of the last quarter of the 18th century. Although he was aware of and very much in favour of technological innovation, Smith was writing before the British Industrial Revolution got into full swing. In this sense, some critics may claim that Smith's views on economies became quickly outdated when those economies became industrialised.

On Self-Interest

Smith's ideas on moral philosophy inform his political philosophy. Smith explains his view that self-interest and the common good are the same thing:

Every individual exerts himself to find out the most advantageous employment of whatever his capital can command. The study of his own advantage necessarily leads him to prefer what is most advantageous to society.

(Cameron, 277)

For Smith, self-interest rules all economic transactions. He states:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

(Chisick, 220).

Further, Smith believed that the rich might well become greedy and rapacious in their pursuit of their self-interests, but because an individual has a physical limit on the things they can consume, the rich are ultimately obliged to dispense their wealth amongst those less rich. In other words, it does not really matter if we actively distribute wealth equally or not since the 'Invisible Hand' will inevitably find its own true distribution of wages, prices, and profits. This self-interest, Smith argues, will even guide the rich to actively help the less well-off. Here, again, is Smith's belief in a reasoned inner self that guides one for the better good of all.

Measuring Wealth

To return to the original objective of The Wealth of Nations, Smith was particular about how the 'wealth' of a nation was to be measured. He did not believe the amount of a nation's gold or silver was an accurate measure of its prosperity since these commodities fluctuate in value over time. It is a fallacy to confuse money with wealth since the former is only the means by which the latter is distributed or redistributed. Some modern economists rather like this idea, which is why investors are not too concerned if a nation has tremendous debt as long as that nation has the potential to increase its wealth. Smith believed that real wealth is measured by examining the "annual produce of the land and labour of society" (Yolton, 549). He stressed that both agriculture and manufacturing needed to be considered, which was in contrast to some contemporary thinkers who believed only agriculture mattered (a position known as physiocracy).

Smith also believed that seemingly unproductive workers had to be considered in this wealth assessment, people like merchants, since they, too, contributed to productivity by creating investment and larger markets for those who did produce things. The only workers Smith considered unproductive were domestic servants.

For Smith, real wealth is the land, labour, skills, and physical goods of a nation. As a consequence of this new criteria for measuring wealth, Smith believed that specialisation of the labour market would greatly increase efficiency and increase the wealth of the nation. He gives the example of a worker skilled in operating a machine that makes pins and how ridiculous (and unprofitable) it would be to ask that worker to first mine the metal and perform all the other tasks necessary to make pins. In addition, money must be invested to increase the nation's wealth and not, for example, be left sitting in bank accounts where money becomes worthless; the rich must be encouraged to invest their surplus into the economy (and so make themselves more money in the process). Certainly, Smith believed that most business owners and merchants were rapacious and their instincts to make money at the expense of others did need to be curbed by a strong government, preferably a monarchy. These latter points are often conveniently ignored by some modern commentators who wish to present Smith as an advocate of a free-for-all economy, that is, an unregulated financial jungle where the strongest (or richest) survive.

Death & Legacy

Smith only wrote two major works, and from 1778, he worked as a customs commissioner in Edinburgh. His aged mother came to live with him since he had never married, although she did have to share the house with her son's library of 3,000 books. Adam Smith died in Edinburgh on 17 July 1790. He was buried in the churchyard in the Canongate area of the Scottish capital close to where he had lived.

Smith was one of the leading figures of the Enlightenment, and he has become one of the most quoted thinkers by economists ever since. The historian A. Gottlieb goes so far as to describe The Wealth of Nations as "the founding text of modern economics" (198). The book took a while to establish a wider audience, and it really only came into its own during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century when it became almost a bible of economics, a position it still holds today for those who advocate 'less is more' when it comes to regulating trade and economies. It is also true that Smith's 'bible', just like the Christian Bible, is very often only selectively plundered and quoted to support specific preconceived ideas. In the case of The Wealth of Nations, quoting only the arguments for a minimisation of state intervention does not give a true vision of what Smith himself believed in. As the historian H. Chisick notes, "It is a matter of regret that most economists in the West seem indifferent to something that Smith and his contemporaries knew full well, namely, that economics cannot properly be separated from social and political policy" (221).