Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962), a lieutenant-colonel in the Nazi SS, was responsible for organising the transportation of Jewish people and other victims of Nazism to concentration, labour, and death camps. Eichmann played a key role in the Holocaust and murder of 6 million Jews but escaped capture after the Second World War (1939-45). He later fled to South America.

Living under a new identity in Argentina, Eichmann's past eventually caught up with him when Israeli agents identified and captured him in 1960. Eichmann was removed to Israel where he faced trial for crimes against humanity. Found guilty, Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging. Unrepentant to the end, he was executed on 31 May 1962.

Early Life

Adolf Eichmann was born in Solingen, Germany, on 19 March 1906. When Adolf's mother died in 1910, the family moved to Austria. In Linz, Adolf's father worked as a manager of a power and tram company. Ironically, given later events, at school Adolf was "taunted because of his dark appearance and small stature as 'the little Jew'" (Boatner, 150). Following in his father's career, Adolf enrolled at the Linz Higher Institute for Electro-Technical Studies, but he left after two years. Adolf then worked as a travelling salesman for several power and construction companies, but he was ambitious to represent a power of a very different kind.

An Austrian Nazi

On 1 April 1932, Eichmann joined the Austrian Nazi Party. In this period he transformed himself from the shy and melancholic boy he had once been into a "loud, hard-drinking, swaggering extrovert" (Boatner, 150). In 1933, Eichmann joined the SS (Sturmabteilung), the elite Nazi paramilitary group in September 1934. Jews, loosely identified by the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, were deemed by the Nazis as enemy number one, blamed for the economic problems of the 1920s and '30s and considered racially inferior. Eichmann specialised in Jewish affairs and briefly visited Palestine in 1937. By 1938, Eichmann was head of the SS Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna. Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, had brought about the Anschluss or union with Austria that same year, and plans were now put in place to force as many Jews as possible to leave what Hitler called his Third Reich or Greater Germany.

Eichmann excelled at his job of expelling Jews from the Reich. He became obsessed with targets, regularly inspecting his team so that they met their quotas and everything was as efficient as it could be. Eichmann employed all kinds of ruthless measures which obliged thousands of Jews to emigrate against their wishes, often forgoing their personal property rights. The money gained from wealthier Jews in this programme was used to pay the transport costs of the poorer ones. Eichmann's success in forcing Jewish people out of Vienna was duly noted by Hitler. Accordingly, in August 1938, Eichmann was moved to Berlin where he was made director of the new Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration. In 1939, Eichmann's forced emigration policies and Eichmann himself were seen in Prague, later, he would personally repeat his policies in Hungary. In December 1939, Eichmann joined the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police.

Eichmann was also put in charge of a secret project known as the Madagascar Plan, that is, to deport 4 million Jews to the island of Madagascar (then a French colony). The project included, with typical Nazi flair for efficiency, the emigrants being required to pay their own costs of transport. The Madagascar Plan was ultimately abandoned as impractical and replaced by an entirely more diabolical scheme.

The Final Solution

Eichmann reached the rank of Obersturmbannführer or lieutenant-colonel in the SS. In the autumn of 1941, he was appointed the head of Section IV 4b of the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office or Reichssicherheitshauptamt). The innocuous name of Eichmann's section hid its real function as the Nazi Race and Resettlement Office, which was responsible for carrying out Hitler's Final Solution, that is, the extermination of European Jews. Eichmann was made fully aware of the Final Solution when he attended the Wannsee conference (in a suburb of Berlin), which was chaired by the RSHA's head and Eichmann's immediate superior Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942), on 20 January 1942. Eichmann took the minutes at Wannsee, and he would act as Heydrich's principal lieutenant; together they drew up a new diabolical protocol. Those arrested as Jews were to be deported by train to the eastern side of the Third Reich to former Polish and USSR territories where they would be held in labour camps. Those detained who could not work (the vast majority) would be sent to specially converted death camps such as Auschwitz. The plan, kept highly secret and always indirectly referred to within Nazi circles, was to be called the Final Solution in reference to several previous attempts by the Nazi regime to remove those identified as Jews from Greater Germany.

Dr Robert Kempner, during his research conducted while he was a prosecutor in the post-WWII Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals, discovered a file of documents related to the Wannsee conference. On the back of the file was the single note: "Final Solution of the Jewish Question". The discovery of the file came too late for use in the main Nuremberg trials, but this first vital documentary evidence as to when Hitler gave the order for the Holocaust to begin was used in subsequent trials for war crimes.

At Wannsee, Heydrich boasted he would see that 11 million Jews were eliminated. Heydrich was assassinated in Prague by the Czech Resistance in May 1942, but this did not impede the awful progression of the Final Solution. Eichmann was instrumental in this process, as here recounted by Dr Wilhelm Höttle, an SS official in the RSHA:

I should like to describe Eichmann, so to speak, as a transporter of death, as a man with, basically, a small brain and an incredible organisational talent. He succeeded first of all in getting out the Jews who wanted to emigrate – two-thirds of the Austrian Jews were saved by this. And in exactly the same way he succeeded, later, once the extermination order was in force, to get the Jews into the extermination camps…Eichmann did everything he was ordered to. He was possessed by carrying out his duty: he had a certain inferiority complex; he had not achieved much in his life before he was in the SS and wanted to show how clever and hard working he was. And that was the bad thing about him…

(Holmes, 318-9)

Those the Nazis identified as Jews, and other so-called enemies of the state such as Romani people, Jehovah's Witnesses, freemasons, and homosexuals were put on trains and removed from the cities and towns. In order to minimise resistance, assurances were given that the trains were taking people away from the terrible ghettos to a new and better life. Eichmann himself gave these assurances, for example, he promised to a group of Hungarian Jews:

Jews: You have nothing to worry about. We want only the best for you. You'll leave here shortly and be sent to very fine places indeed. You will work there, your wives will stay at home, and your children will go to school. You will have wonderful lives.

(Bascomb, 6)

The real destination was labour camps or death camps in Germany and Poland, but many thousands died on the trains from suffocation or dehydration, such were the terrible conditions in which they were transported. Part of Eichmann's later defence against the charge of crimes against humanity was that he had not personally killed anyone or had anything to do with the death camps, only the transportation of people to those camps. However, the brutal conditions of the transport trains resulted in thousands of deaths. Zeev Sapir, an eyewitness, reported that everyone, men, women, and children were first stripped of their clothes, any valuables were removed, and their documents were shredded. Anyone who resisted was badly beaten. Sapir and 102 other Jewish people were then crammed into a cattle car meant to hold just eight cows. Those inside were given a single bucket for use as a toilet and a single bucket of water to drink. The journey lasted four days, and no food and no more water was given. Sapir arrived at Auschwitz, but some of the people in his car died on the journey.

Camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau were deliberately engineered for mass extermination. People were forced into gas chambers, which could hold up to 2,000, and then murdered using poisonous gas. People were often told they were going to be disinfected for lice in showers inside the death chambers. Other prisoners emptied the chambers of corpses to make them ready for the next group. Malnutrition and disease also claimed countless lives in the terrible living conditions of the camps. The horrors that happened in these camps are well documented by surviving prisoners, by those who worked in them, and by those Allied soldiers who liberated them at the end of the war. The experience is perhaps not possible to comprehend by outsiders. Even those who witnessed and survived it, in many cases, could not live with what they had seen. Thousands of prisoners had thrown themselves against electrified fencing, and a significant number of those liberated later committed suicide to escape the recurring horror.

Eichmann pressed on regardless with his terrible mission. He saw that Jews and other "enemies" were eliminated in newly captured territories when the German military made significant advances. This was done by mobile killing squads known as Einsatzgruppen, which rounded up people for transportation or simply executed en masse entire villages. Eichmann himself estimated that the Einsatzgruppen were responsible for 2 million deaths. Eichmann had no qualms about the killing of children either since he considered their deaths necessary in order to avoid a new generation that might look for vengeance against those who had murdered their parents. Eichmann certainly approached his job with gusto, a fact frequently noted by his SS colleagues. He once stated, "I will leap laughing to my grave because the feeling that I have five million people on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction" (Boatner, 150). As the killing went on and the figures rose, Eichmann again told a subordinate, "I'll die happily with the certainty of having killed almost six million Jews" (ibid).

Eichmann Escapes

As WWII came to a close, Eichmann fled into the Austrian Alps with a motley group of SS subordinates, ordinary soldiers, and some members of the Hitler Youth. His initial orders were to establish a resistance group there, but he then received his last order, which was not to fire on Allied troops. The war was over. Germany had surrendered. Eichmann visited his wife and three children outside Altaussee, and knowing he would be hunted down as a war criminal, he gave a last goodbye and told them he would contact them once he had safely established himself out of harm's way. Already, the Allies had formed special units whose purpose was to round up suspected war criminals. As martial law was declared and checkpoints set up everywhere, Eichmann could not escape for long.

Eichmann was arrested by Allied forces while heading to Salzburg. He gave a false name and claimed he was a member of the German Air Force. He was detained in a US-run internment camp, but this was only a rudimentary affair with a single enclosure wire. Eichmann escaped from the camp and continued to Salzburg. He was caught again and detained in a camp at Ober-Dachstetten in southern Germany, but, still not recognised for who he was, he again escaped, this time with the help of fellow SS inmates. One night, climbing over the barbed wire fence and dashing into the forest, Eichmann disappeared without trace. We know now that the fugitive worked for several years in Germany, first as a lumberjack and then as a chicken farmer, ironically selling his eggs on the black market to mostly Jewish customers.

The rest of the world was not quite sure what exactly had happened to Eichmann. At the Nuremberg trials, fellow Nazi Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946) had told his interrogators that Eichmann had been killed and even described in detail the circumstances of his death, a common ploy to avoid fellow Nazis being hunted down. In another twist, a Jewish revenge group claimed to have apprehended Eichmann in the Austrian Alps and shot him dead. There were also rumours Eichmann had been killed in Czechoslovakia.

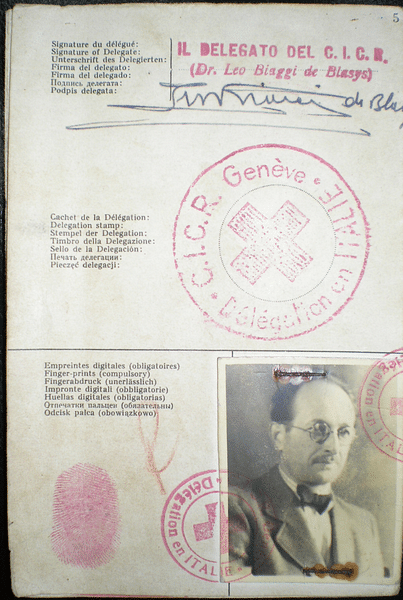

In reality, Eichmann was surviving under a false identity in Germany, but by 1950, he had decided it was too dangerous to remain in Europe. Assisted by Nazi sympathisers, Eichmann, like so many other Nazi criminals, travelled along a well-established network of safe houses from Germany to Austria to Italy and then his final destination, Argentina. He was given a new passport, and he sailed third class from Genoa to Buenos Aires in July 1950, carrying in his pocket a souvenir of German soil. Once again, as it had for other notorious Nazis like Josef Mengele (1911-1979), a secret network that involved senior figures of the Argentine government and the European Catholic Church had succeeded in removing a war criminal from the justice they deserved. Thanks to the Nazi network in his new homeland, Eichmann gained a job in a Volkswagen factory and then a hydroelectric company. In July 1952, Eichmann's wife and children joined him, but he told the children, lest they talk carelessly to strangers, that he was their uncle.

The Hunt for Eichmann

Eichmann may have escaped for now, and the secrecy of the Holocaust in Nazi circles and his deliberate policy of not having himself photographed obscured the trail of the SS lieutenant-colonel, but one man, in particular, was determined to bring Eichmann and other Nazi war criminals to justice.

Simon Wiesenthal (1908-2005), himself a survivor of Nazi concentration camps, became known as the 'Nazi Hunter', and in his research, he noted the regular appearance of Eichmann's name in the testimony of Holocaust survivors. In 1953, Wiesenthal received confirmation that Eichmann was living near Buenos Aires under the name of Ricardo Klement. Wiesenthal passed on this information to the Israeli authorities, but it was not until 1960 that Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, hatched an audacious plan to kidnap Eichmann and bring him to Israel for trial. Abducting Eichmann contravened Argentine sovereignty, but the Israelis announced they had secured Eichmann on 11 May 1960. The operation had involved over 10 agents and weeks of preparation, but Eichmann was finally abducted as he stepped off a bus in a suburb of Buenos Aires. The time for a reckoning had come.

Eichmann's Trial & Execution

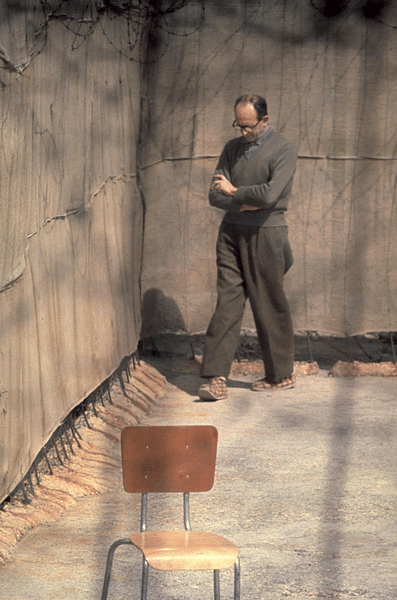

Eichmann was first interrogated extensively, not least to ascertain the whereabouts of other fugitive Nazis. Believing he had a chance of receiving only a prison term, Eichmann was very cooperative with his interrogators. Eichmann's trial for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against the Jewish people lasted from April to August 1961. The court wished to demonstrate not only Eichmann's guilt but, as at the Nuremberg trials, also reveal the full scale of the Holocaust's horrors and so inform a new generation of just what had happened under Nazi rule. Witnesses included those who had personally seen Eichmann in action performing his SS role. The former SS officer was protected in the court by a bulletproof glass screen. Eichmann was unrepentant of his actions and, in any case, excused himself by saying he was merely following the orders of his superiors and was only involved in the transportation of people to the camps, not what happened to them there: "I had orders but I had nothing to do with that business", he said (Cimino, 216). Eichmann rested his defence on his claim that he was a mere bureaucratic cog in a vast Nazi killing machine.

Eichmann was found guilty and sentenced to death. It was the first time an Israeli court had ever passed and then actually imposed such a sentence. The convicted criminal, visibly shaken, gave a bewilderingly inappropriate response upon hearing his sentence: "My guiding principle in life has been the desire to strive for the realisation of ethical values" (Thomas, 124). Eichmann appealed first the judgement and then for clemency, but both appeals were rejected. Eichmann was unrepentant, he remarked to a Protestant missionary who visited him in his cell: "I did nothing wrong. I have no regrets" (Bascomb, 318).

Adolf Eichmann was hanged at midnight on 31 May 1962. His body was cremated, and the ashes were scattered in the neutral waters of the Mediterranean Sea. As with some of the senior Nazi defendants at the Nuremberg trials, Eichmann had impressed the public only with the banality of his personality and his uncomprehending attitude to the enormity of the horrors he had been responsible for. Indeed, a controversial book was published in 1963 on Eichmann by Hannah Arendt with the title Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Eichmann had, in the end, inadvertently helped the enemy he had strived so hard to eliminate. The Nazi's dramatic capture and trial did significantly raise interest in learning about the Holocaust and, 17 years after the war had ended, helped ensure that the atrocities he had been responsible for were once again documented for all to see, helping to ensure they would never be forgotten.