Aethelred II, also known as Aethelred the Unready, was king of the English from 978-1013 and 1014-1016. His long reign was initially stable, but Viking attacks on England escalated from the 990s onward. Viking incursions eventually grew so serious that England struggled to mount effective resistance, and Aethelred was briefly overthrown by the Danish king Swein Forkbeard in 1013.

Aethelred reclaimed his kingdom following Swein’s death in early 1014, and the “second reign” of Aethelred saw more effective military campaigns against the Vikings but also high levels of disunity and suspicion at Aethelred’s court. The king died in 1016 and passed along the Viking struggle to his son Edmund II. Aethelred reigned for nearly 38 years – longer than any other king of England before the Norman Conquest.

Aethelred’s infamous nickname, the Unready, does not actually refer to him being unprepared. It is an Old English pun that mocks Aethelred’s given name, which meant “Noble Counsel.” The Old English word unraed meant “bad counsel” and was a way to note the irony that a king named “Noble Counsel” struggled to maintain the loyalty of the English nobility. As the English language evolved, unraed was corrupted into unready, even though Aethelred the Ill-Advised would be a more accurate translation.

Path to the Throne & Early Reign

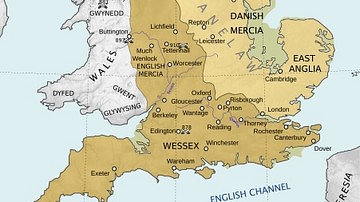

Aethelred was born sometime between 966 and 968 in a recently united England. He was the son of King Edgar (r. 959-975) and Queen Aelfthryth. Edgar was arguably the first king to see England remain one stable, coherent kingdom for an extended length of time, as his three predecessors had seen England fragment back into smaller kingdoms at one time or another. However, when Edgar died in 975, England once more found itself bitterly divided and possibly on the brink of splintering again. Edgar had died with three surviving children, each from a different mother. The English nobles managed to preserve the unity of their kingdom by eventually agreeing that the eldest child, the teenage Edward, should be the next king. Evidently not everyone was pleased with this arrangement, and Edward was assassinated in 978, just three years into his reign.

After Edward’s murder, Aethelred was the only surviving son of Edgar, ascending to the throne at somewhere between ten and twelve years old. Aethelred’s mother Aelfthryth and his influential tutor, Bishop Aethelwold, were among the most prominent figures at the young king’s court. When Bishop Aethelwold died in 984, King Aethelred began to exert more influence. Aethelred expelled his mother from court and began surrounding himself with new appointees rather than relying on the old guard. He married Aelfgifu of York around this time as well, and they soon had several children, including the future King Edmund II.

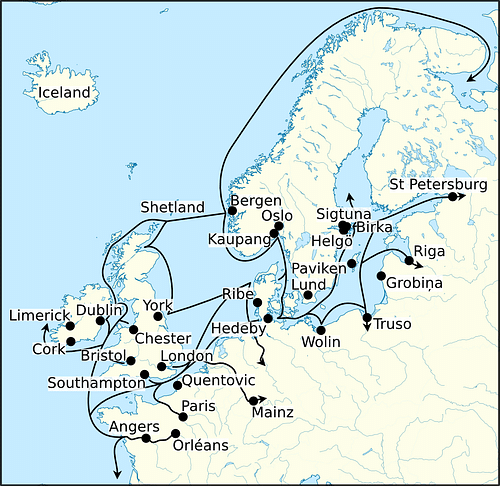

A few small Viking raids were launched against England in the 980s, and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that these fleets often amounted to no more than a handful of ships. Local English forces sometimes took care of them on their own, such as when a group of Vikings was defeated in Devon, according to The Life of St. Oswald. Sometimes the Vikings disappeared for years at a time, such as from 983 to 987, when no attacks were recorded at all. In spite of isolated raids, Aethelred ruled over a stable and wealthy kingdom in the 980s, free to focus on assembling his own core of advisors and asserting his newfound authority.

Paying the Danegeld? The Viking Problem Escalates

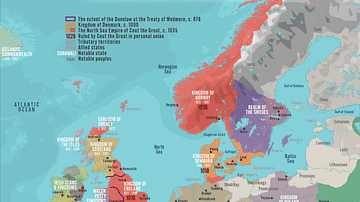

In the 990s, England saw the first large Viking invasions of Aethelred’s reign, led by Olaf Tryggvason, a warlord from Norway, and Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark. The English response is characterized by The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as a series of near-misses and narrow defeats: the English resisted fiercely at the Battle of Maldon in 991 but were defeated; Aethelred assembled a fleet to defend his shores in 992, but it failed to stop the Vikings; an army confronted the Vikings in 993 but fell apart when three of its leaders fled.

After repeated attempts to defend England by military means, Aethelred offered tribute payments to the Vikings twice during this era: once after the Battle of Maldon in 991 and again in 994. The use of tribute – the act of paying off an enemy to avert destruction – is one of the most controversial and misunderstood aspects of Aethelred’s reign. Writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries frequently accused him of trying to solve England’s problems with money, which allegedly only encouraged his Viking enemies to come back in search of more. However, Aethelred’s Victorian-era critics failed to recognize the context of Aethelred’s time, when such tactics were common and acceptable. Aethelred only paid tribute after trying military resistance first, and tribute was also offered by rulers like William the Conqueror (c. 1027-1087) and Alfred the Great (r. 871-899).

Aethelred’s use of tribute put a stop to the massive invasions of the 990s. He also began to embrace a form of “penitential kingship,” seeking to restore England’s favor with God by amending his own ways. The king restored properties that he had seized unjustly in his youth. He also removed unscrupulous favorites and brought back his mother, Queen Aelfthryth, who had been absent from court for nearly a decade.

The New Millennium

As the year 1000 approached, there were some reasons for optimism in England. The severe invasions of the early 990s had given way to smaller Viking fleets, and Aethelred did not need to offer any tribute payments between 994 and 1002. Anglo-Saxon literature was also flourishing. Some of the most prolific writers of Old English were active during Aethelred’s reign, including Aelfric of Eynsham and Wulfstan II of York. The surviving manuscript of Beowulf – probably the most famous work of the entire Anglo-Saxon period – is generally thought to have been copied down sometime during Aethelred’s long reign. Another of the great Old English poems, The Battle of Maldon, also originates from this time, commemorating the tragically heroic defeat of 991.

Aethelred himself was on the move at the turn of the millennium, attacking Norse-influenced regions. He had the Isle of Man raided in 1000 and personally led an English army to Strathclyde the same year, plundering and ravaging the entire area, according to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. An English fleet was sent to raid in Normandy around the same time, which may have been a catalyst for Aethelred’s marriage to Emma, the sister of the Norman duke, in 1002.

But that same year, Aethelred got wind of a Viking-led plot to kill him and overthrow his administration. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that in response, the king ordered that “all Danish men who were in England” should be killed on November 13, 1002. It became known as the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, named for the feast day on which it fell, and is perhaps the king’s most infamous act. While historians of the 20th century regarded St. Brice’s Day as attempted genocide, recent reassessments and archaeological finds have shifted this perception. It is now thought that the massacre was smaller in scale and targeted at Scandinavian warriors in England, especially those who were serving Aethelred as mercenaries. However, Aethelred himself admits in a charter from 1004 that St. Brice’s Day had resulted in the deaths of people seeking sanctuary in a church in Oxford, and the king sounds proud of his actions, calling it “a most just extermination.”

Swein & Thorkell’s Invasions

In the mid and late 1000s, England was again plagued by serious invasions from Scandinavia led by the Danish king Swein and a powerful Danish warlord named Thorkell the Tall. Their marauding armies were able to stay in England for years at a time. Aethelred and his nobles sometimes managed to catch the Viking armies, though. An English leader named Ulfcytel fought a fierce battle against Swein’s army in 1004. The Vikings “said that they never met worse fighting in England than Ulfcytel dealt them,” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recalls. King Aethelred, leading his army in person, intercepted Thorkell’s forces in 1009, but neither side attacked the other. Historian Tom License has suggested that containment itself may have been one of Aethelred’s goals.

Aethelred constructed a new English fleet in 1009 and orchestrated a massive armor-building campaign. The efforts amounted to about 200 ships and thousands of helmets and mail coats, but a lack of unity at court undermined these efforts. As the English fleet amassed at Sandwich, a feud between two nobles led to 100 ships being destroyed, and Aethelred decided that the remaining ships should retreat to the Thames.

The king ordered out army after army with diminishing returns, and by 1012, English resistance to Thorkell’s army had collapsed. An especially large tribute payment was rendered that year, which stopped the raiding but did not prevent drunken Vikings from murdering the Archbishop of Canterbury – one of the lowest points of the entire war. Finally, Aethelred convinced Thorkell to switch sides after the tribute payment of 1012, turning his opponent into an ally. Thorkell, now rich from his tribute payments, became Aethelred’s defender.

The next year, Swein returned with a large army. England had endured years of warfare and high taxation, and Swein received submission from each shire he marched through. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives the impression that no leaders were willing to fight back except for Thorkell and Aethelred, who successfully defended London. When Swein returned later in 1013, however, the Londoners recognized that they could not hold out forever. London abandoned Aethelred, who sent Queen Emma and their young children to Normandy for their safety. Aethelred stayed behind at first, but soon escaped to the Isle of Wight. By the end of the year, he too was in exile with his family in Normandy.

Comeback & Second Reign

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers to Swein as “full king” of England by late 1013, even while Aethelred was still resisting from London. Aethelred’s flight to Normandy only confirmed the obvious: Swein had conquered England. Swein was planning for his dynasty to continue in England and had his son, Cnut, marry a prominent English noblewoman named Aelfgifu of Northampton. But Swein suddenly died on February 3, 1014. It had only been a handful of weeks since Aethelred left for Normandy.

Cnut asserted his right as his father’s heir and was proclaimed king by the Viking fleet. But some of the English nobles saw an opportunity to reverse the Danish Conquest. They asked Aethelred to return to England and reign again. They had conditions, though: in order to be accepted back as king, Aethelred had to agree to “govern them more justly,” in the words of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The nobles also asked him to forgive anything that had been done against him. Aethelred agreed, and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says he then “came home to his own people and he was gladly received by them all.”

With an army at full strength, Aethelred marched to Lindsey (modern day Lincolnshire), where Cnut and his Vikings were encamped. Aethelred and his army killed everyone they could find, inflicting a serious defeat on Cnut and his allies. Cnut managed to escape the slaughter, and the Encomium Emmae Reginae includes the detail that Cnut returned to Denmark with noticeably fewer ships. Aethelred had expelled a Viking army by force, the first time in generations that an English king had done so.

Despite an impression of unity given by The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, not everyone would have been happy to see Aethelred return, especially considering that some noble families had offered hostages to Swein and Cnut. Scandinavian sources say that Aethelred did meet some resistance and fought in at least two more battles after his return to England: with the help of Viking mercenary Olaf Haraldsson, Aethelred retook London, and he and Olaf won a battle against Ulfcytel, the same leader who had stoutly resisted Swein in 1004.

With England re-conquered, Aethelred felt confident enough by 1015 to return to his old ways. Two nobles who had likely supported Cnut were assassinated on the orders of Eadric Streona, the powerful ealdorman of Mercia who sometimes acted as the king’s enforcer. Aethelred then seized their lands. In spite of his promise to rule “more justly” in his restoration agreement of 1014, the king was returning to his practice of purging his nobles in violent ways, which he had previously done in 993 and 1006. The king’s eldest surviving son, Edmund, had apparently been close to the assassinated nobles and decided to rebel. The king normally reacted to acts of disobedience, real or imagined, with swift punishment, but he was unable to move against Edmund in 1015 because he suddenly fell ill.

While Edmund was in rebellion and the king was incapacitated, Cnut returned with a fresh fleet. Cnut soon had the support of the powerful Eadric Streona, who changed sides after Aethelred fell ill. With Eadric’s help, Cnut campaigned up and down England in 1015 and 1016. Edmund rode out with his own armies but failed to oppose them.

Death & Legacy

Edmund realized that he needed his father’s help to defeat Cnut and asked the king to lead out the army from London. Aethelred agreed and marched on the final campaign of his life. However, upon joining up with Edmund’s troops, Aethelred received intelligence that he was about to be betrayed. Sick and fearing for his safety, Aethelred went back to London, where he died on April 23, 1016. He was about 50 years old.

The English resistance passed to Edmund – now King Edmund II – who confronted Cnut in a rapid series of battles and skirmishes throughout 1016. Edmund, nicknamed “Ironside” for his military abilities, seemed to be gaining the upper hand. However, Cnut dealt him a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Assandun on October 18. Edmund died a few weeks later, cementing Cnut as England’s next king. The Danish Conquest of England was complete, and Cnut and his sons would rule England for a generation. Aethelred’s son Edward the Confessor eventually restored his dynasty to power in 1042 and ruled until just before the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

Medieval writers remembered Aethelred in vastly different ways. Some English sources, like The Life of St. Oswald and John of Worcester, summarize Aethelred positively, as a graceful and handsome ruler. Other English writers, like William of Malmesbury, recorded dubious tales of the king’s debauched and lazy lifestyle, portraying him as addicted to wine and women. William’s depiction contributed to a downturn in Aethelred’s reputation in England that he never fully recovered from. In Scandinavia, Aethelred’s reputation went the opposite way, with sagas depicting him as an effective and warlike ruler, little different than his Viking opponents: Aethelred is “a good prince” that armies “feared as a God” in the Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent’s Tongue. Aethelred appears as “a true friend of warriors” in a saga in honor of Olaf Haraldsson, the mercenary who had campaigned with him in 1014.

Likewise, modern historians have interpreted Aethelred’s long and complex reign in many different ways, and they are still divided over whether Aethelred was a failed king, an underrated survivor, or something in between. Perhaps the most succinct assessment of Aethelred is also the oldest one: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, just a few years after Aethelred’s death, eulogizes him with some sympathy as a king who “had held his kingdom with great toil and many difficulties.”