Aethelstan was the first King of England, ruling from 927 to 939. The son of Edward the Elder (reign 899-924) and grandson of Alfred the Great (reign 871-899), he inherited the southern-based Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons in 924 before capturing Viking York in 927 and establishing rule over northern England. He would do much to unite the various peoples of his kingdom, including the Mercians, West Saxons, Danes, and Northumbrians, under his rule by holding national councils, reforming laws, and encouraging unity through a common Christian faith.

His influence extended beyond England as he subdued the kings of Wales, Scotland, and Strathclyde and forged alliances with the rulers of France, Germany, and Norway. His greatest test came in 937 when an alliance of Scots, Celts, and Vikings attempted to conquer northern England. However, the defeat of the invaders at the Battle of Brunanburh marked a pivotal moment, the first great victory of the united English kingdom.

Much of what we know about Aethelstan comes from a contemporary set of annals, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which provides key but limited details, expanded upon by the 12th-century historian William of Malmesbury, who claimed to be working from a now lost ancient book on the king. As Aethelstan was a great patron of William's Malmesbury Abbey, William understandably admired the king, who, he believed, was "extremely beloved by his subjects from admiration of his fortitude and humility, [and] he was terrible to those who rebelled against him, through his invincible courage." He also tells us the king was "of becoming stature, thin in person, his hair flaxen," which – according to William's own investigation into Aethelstan's coffin – was "beautifully wreathed with golden threads" (Sharpe, 134).

Youth

Aethelstan was born in 894 to Edward and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Edward, still a young man, was the heir to the southern Kingdom of Wessex, ruled by his father, Alfred the Great, who stoutly led the resistance against the Viking invaders, defeating them at the Battle of Edington in 878 after they had conquered northern and eastern England.

Alfred was particularly fond of his grandson. When Aethelstan was about five years old, Alfred held a public ceremony for the young prince, gifting him a scarlet cloak, a diamond-studded belt, and a sword with a golden scabbard, displaying the boy as a 'throne-worthy' prince. Aethelstan was then sent to the West Midlands to be fostered under the care of Alfred's daughter, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians (reign 911-918), and her husband, Aethelred, Lord of the Mercians (reign 881-911), a loyal vassal of Wessex.

Later praised as the "best-educated ruler they [the English] had ever had," Aethelstan was taught to read and write in both English and Latin (Foot, 29). He also likely studied classical works of theology and philosophy, including Augustine of Hippo's Soliloquies and Boethius' The Consolation of Philosophy. Equally importantly, he was trained in riding, hunting, hawking, and Anglo-Saxon warfare.

When Edward became King of Wessex upon his father's death in 899, his first major decision was to set aside Aethelstan's mother, Ecgwynn, who was of minor political standing, in favour of a more prestigious consort, Aelfflaed of Wiltshire. His new bride was the daughter of Ealdorman Aethelhelm of Wiltshire (d. 897), a powerful lord who had been one of Alfred's leading military commanders. While the union enhanced Edward's position, it undermined Aethelstan's, as the son of Edward's second marriage, Aelfweard, would now boast a superior maternal lineage to his older half-brother. Aelfweard also grew up in Wessex beside his father, forming ties with the kingdom's power brokers, while Aethelstan was far away in Mercia.

Yet Aethelstan embarked on a perfect royal apprenticeship. Now led by Aethelflaed, following her husband's death in 911, the Mercians waged war on the Vikings of the East Midlands. As one of his aunt's chief lieutenants, Aethelstan led troops and built fortresses on her behalf, earning him renown and respect among the Mercians. When Aethelflaed died in 918, and Mercia passed to her brother, Edward, Aethelstan continued in this role and perhaps even acted as his father's deputy in Mercia, gaining experience in both politics and warfare.

Succession & the North

Following a reign of success in war and the expansion of his kingdom, Edward died in the summer of 924. However, his succession plans were unclear. The Mercians and the West Saxons each summoned their own witan (council of lords and bishops) to discuss the succession, with the West Saxons naming Aelfweard their new king. Aethelstan, they reasoned, had been away from home for too long and was now more Mercian than West Saxon. Even more scandalously, rumours began to spread that Aethelstan's mother was actually Edward's concubine rather than his lawful wife, conveniently weakening Aethelstan's claim to the throne. Yet, as preparations for Aelfweard's coronation were being made, only two weeks after Edward's death, he too died. It was now the Mercians' turn to act, declaring Aethelstan king, and the West Saxons, preserving the union between the two realms, agreed to receive him as their ruler.

His coronation took place the following year at Kingston-upon-Thames, a royal estate near London, on the border between Mercia and Wessex. Here, he swore to rule equally over both peoples, under the title used by his father and grandfather, "King of the Anglo-Saxons". Yet, in addition to promoting unity and continuity, Aethelstan's coronation also expressed his lofty ambitions. An Anglo-Saxon king was traditionally invested with a ring, a sword, a sceptre, a rod, and a ceremonial war helmet at his coronation. But when Aethelstan kneeled before Archbishop Aethelhelm of Canterbury, instead of a helmet, a crown was placed atop his head. The new king was making clear his aspirations for imperium over Britannia, the lands ruled by the emperors of Rome, who had once adorned crowns on their coins, and styling himself after Charlemagne (reign 768-814), the Frankish king who was crowned as a restored Roman emperor in 800.

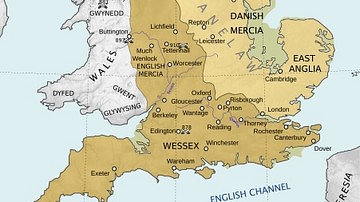

Aethelstan's inheritance encompassed present-day southern England (Wessex), the Midlands (Mercia), and East Anglia (conquered from the Vikings by Edward). To his west, guarded by Offa's Dyke, were the various Welsh kingdoms, and to his north was the Viking Kingdom of York. Aethelstan had initially negotiated a peace with King Sihtric of York (reign 921-927) in 926. Yet when Sihtric died the following year, and his brother, Guthrith of Dublin (reign 921-934), sailed east to take up his throne, Aethelstan marched north, taking York first and naming himself master of the city.

Though the northerners generally regarded southern kings with suspicion, many Christians remained in the region. Thus, making common cause, Aethelstan made the northern church a partner in his governance of Northumbria, granting vast tracts of land to the Archbishopric of York to ensure its loyalty and support. He also visited the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral, bestowing gifts upon the saint, who was admired more than any other in the north.

Upon securing York, Aethelstan summoned several northern rulers from Scotland, Strathclyde (a northwest Celtic kingdom), and Bamburgh (English lands north of Yorkshire) to a meeting at Eamont Bridge in Cumbria, on the northwest frontier of his kingdom. Here, they all swore loyalty to Aethelstan and, as Christian kings, promised never to ally with the pagan Vikings. Certainly, Aethelstan had one eye on Sihtric's ambitious relatives at Dublin, who still claimed York.

After establishing his northern imperium, he then returned south to Hereford, near the Welsh border, where the Welsh kings likewise submitted to his authority, collectively giving an annual tribute of "twenty pounds of gold and three hundred pounds of silver, and to hand over by the count 25,0000 oxen, besides as many as he might wish of [hunting] hounds…and birds of prey" (Sharpe, 134).

Such was Aethelstan's reputation and the vastness of his kingdom that his rivals had been subdued simply by the threat of violence or, as William of Malmesbury tells us, "by the single terror of his name" (Sharpe, 132). But how would this "King of all Britain," as Aethelstan now called himself, govern and hold together his new empire?

Governance, Law, & Royal Councils

An Anglo-Saxon king traditionally exercised authority via small royal councils comprised of his leading followers. Yet, as the ruler of a newly formed and enlarged kingdom, Aethelstan's councils appeared more like national assemblies, some of which included over 100 lords and clergymen hailing from across England. Described by Michael Wood, these councils "enabled the king to talk to leaders from the regions, confer over crime and punishment, make law, receive ambassadors from abroad and determine policy. Face to face, he could persuade, reward and if necessary threaten" (21).

They would also break down regional separatism. The West Saxons, who had once favoured Aethelstan's brother, and the Mercians, who grew up with Aethelstan, would now sit together at a common council. They were joined by their former rivals, the subjugated Viking warlords from the east and north of England. Meanwhile, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York were united for the first time by a shared political project and could rejoice that their new protector was a genuine man of piety and learning.

The laws decreed by Aethelstan at these councils show an energetic ruler eager to enforce stability. The minting of coins and general trade outside of burhs (walled towns) were outlawed, pushing commercial activity into towns where buying and selling could be regulated by royal agents. These agents ensured that trading disputes were swiftly resolved and that new coins met the required weight and standard of silver. Amongst his sterner laws were the death penalty for thievery - a persistent problem during his reign - although upon further reflection, he later raised the death penalty age from 12 to 15 because it seemed "too cruel to him that a man should be killed so young" (Whitelock, 428). He also provided the first English laws to aid the poor, proclaiming:

It is my wish that you [landowners] shall always provide a destitute Englishman with food, if you have such an one [on your land], or if you find one [elsewhere].

(Laws of Aethelstan)

Aiding the poor and vulnerable, to Aethelstan, was part of his duties as a Christian ruler, responsible for the souls of his subjects. These responsibilities included protecting the church and ensuring pastoral care was offered throughout his kingdom. He also founded new churches at Milton Abbas and Muchelney in southwest England, and several churches and monasteries, including Malmesbury Abbey, benefited from his donations of land, books, and relics. Such generosity attracted scholars and monks from the continent, ensuring these religious houses were well-staffed and continued the educational programmes begun by Alfred.

Family & Foreign Policy

Aethelstan was unusual for a medieval king in not marrying. While he was portrayed as homosexual in the movie Seven Kings Must Die (2023), there is no contemporary evidence for this. Regardless, there were political reasons for him to remain a bachelor. Aethelstan had two very young brothers: Edmund (b. 921) and Eadred (b. 923) – via his father's third marriage to Eadgifu of Kent – whom he effectively adopted and groomed for rule. Marrying and having sons of his own would have inevitably led to a clash between his sons and brothers, and having been involved in the succession crisis of 924, Aethelstan was eager to avoid creating another.

Nor did Aethelstan need to marry to form foreign alliances. He was already well connected with the continent and arranged matches for his sisters to deepen these ties. These links with Europe included a cousin, Count Arnulf (r. 918-965), who ruled nearby Flanders, and a nephew, Prince Louis (r. 936-954), heir to the French throne, although he grew up in England after his family, the Carolingians, were deposed in 922.

As the Carolingian dynasty (former rulers of France and Germany) retreated across Europe, new ruling families emerged and were eager to marry into the more established, prestigious, and successful House of Wessex. In 926, the king's sister, Eadhild, married Hugh, Duke of the Franks, who honoured Aethelstan by gifting him the sword of Constantine the Great and the spear of Charlemagne. A second sister, Ealdyth, married Prince Otto (future King of Germany, reign 936-973) in 930, and another, Aelfgifu, married a Burgundian prince in the same year. These connections helped Aethelstan reinstate his nephew, Louis, to the French throne when he came of age, with his accession in 936 supported by Hugh of France and Arnulf of Flanders.

In addition to Louis, Aethelstan fostered several young foreign princes at his court, including Haakon of Norway (reign 934-961) and Alan II of Brittany (reign 938-952), both of whom were eventually supported with a fleet and soldiers to establish themselves as rulers of their homelands during the 930s. These marriages and interventions made Aethelstan the first English king to be a significant figure in Europe. Indeed, by the late 930s, almost every Christian ruler on Europe's western seaboard was an ally of his.

The Battle of Brunanburh

Aethelstan's conquests and treaties with the northern rulers brought six years of peace across Britain, during which "there was peace everywhere, and abundance of all things," noted one nostalgic chronicler (Campbell, 54). Unfortunately, the peace ended in 933 when King Constantine II of Scotland (reign 900-943), seeking freedom from Aethelstan's overlordship, withdrew his allegiance to the English. In response, Aethelstan led a campaign north, plundering Scotland and suppressing the revolt. Constantine was then dragged south to Buckingham, where he swore loyalty to Aethelstan once more.

However, he had not abandoned his plans. Back home, Constantine began plotting once again – this time with allies including Owain of Strathclyde (fl. 930s), who longed to cast off English overlordship, and Olaf of Dublin (reign 934-939), son of Guthrith, who had lost York to Aethelstan in 927. Having inherited Dublin in 934, Olaf was now feared across the Irish Sea, commanding the loyalty of several Viking sea kings and widely regarded as York's rightful heir. And if York could be reclaimed, the northern kings would gain a buffer state and powerful ally against the English.

The allies sailed and marched into northern England in the summer of 937, meeting at Brunanburh - likely the present-day Wirral town of Bromborough on the Irish Sea. Aethelstan marched slowly from the south, followed by the warriors of Mercia and Wessex along the way, arriving on the Wirral around October 937.

Brunanburh was one of the largest battles of the Anglo-Saxon period, as both sides numbered between 5,000 and 10,000 warriors. Aethelstan personally commanded the left flank of the English army against the Vikings, while Prince Edmund, now 16 years old, led the right against the Scots and Strathclyde Britons. The clash at Brunanburh was a demonstration of great brutality and became known by its survivors simply as "The Great Battle" (Campbell, 54). A horrified contemporary poet, recording the deaths of several of the invasion's leaders, commented, "'Never was there more slaughter on this island" (Livingston, 43). As the battle wore on, late in the day, the English forces broke their foes' shield wall, and chaos spread across their battlelines as the invaders were butchered or fled.

Aethelstan stood victorious, but the cost was high. He lost a large portion of his army, preventing him from re-establishing hegemony over Scotland and Strathclyde. Yet, the battle was a pivotal turning point for the English, remembered as the first great victory in defence of their homeland.

Death & Legacy

On 27 October 939, while holding court at Gloucester, Aethelstan died at the age of 45. The cause of death remains unknown. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle merely states, "This year King Aethelstan died in Gloucester" (Giles, 65). His body was taken to and buried at Malmesbury Abbey. This broke with tradition, as the West Saxon kings were usually buried at Winchester, the seat of Wessex's leading bishop. Yet, the city's preference for Aelfweard in 924 had led to frosty relations with the king. Malmesbury, meanwhile, was a favoured religious house of Aethelstan's and lay on the border between Mercia and Wessex, demonstrating that even in death, he felt equally tied to his West Saxon heritage and his Mercian upbringing.

Unlike his father, Aethelstan had settled his succession, and upon his death, the throne passed to his brother Edmund (r. 939-946), the young veteran of Brunanburh, with the full support of the English lords. However, those Viking settlers in the north and east of the kingdom, whom Aethelstan and his aunt Aethelfaed had conquered, immediately withdrew their homage to the English and summoned Olaf of Dublin to lead them. They might have feared Aethelstan, but Edmund did not (yet) strike terror into the hearts of his enemies like his brother had. He would, however, fight for control of northern England, a battle that would last a generation, ending with a third brother, King Eadred (r. 946-955), who established West Saxon control over Northumbria for the final time in 954.

While his empire crumbled upon his death, during his lifetime, Aethelstan remained unconquered and undefeated in battle. Certainly, contemporaries recognised him as a remarkable ruler. A poet at his court proclaimed that Aethelstan was "renowned through the whole world" (Foot, 94). While an Irish monk praised him as "the pillar of the dignity of the western world," and as far north as Iceland, he was remembered as "Aethelstan the Victorious" (Foot, 106 & 179). Though he achieved a decades-long rule over the whole of Britain, fashioning himself as a later-day Roman emperor, he would ultimately be remembered as the first King of England.