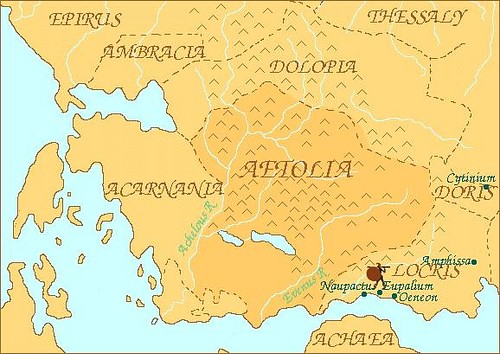

The Aetolian League was an ancient Greek alliance of the tribes that lived west of Athens and north of the Peloponnese. The league was probably first established in the early 4th century BCE, reached its peak during the Hellenistic Period, and survived until the region was annexed by Rome at the end of the Fourth Macedonian War.

Sources & Origin

One of the earlier mentions of Aetolia is alongside Leda, who resided in these lands. She was the daughter of the mythological Aetolian king Thestius and the mother of Helen of Troy. Homer's Book 9 of the Iliad introduces Aetolia as the lands that were terrorized by the Calydonian Boar. The creature was sent by Artemis who was offended by the negligence of king Oeneus to pay his respects according to the tradition. Ultimately, the king sent his son, the Argonaut Meleager, son of Ares, accompanied by the Argonauts' leader Jason, the Dioskouroi, Theseus, and Atalanta. Later on, Diomedes traveled to Aetolia to return the throne to his grandfather Oeneus by imposing justice on his cousins who overthrew the king.

Besides Homer, a figure that acclaimed a significant portion of the ancient sources was Polybius (c. 208-125 BCE), an Achaean-born hipparchus (cavalry general) who was held captive by the Romans. Eventually, he integrated into Roman society and wrote The Histories. Diodorus (1st century BCE), a Greek historian from Sicily, also contributed to our knowledge of the Aetolian League.

The daily life of an Aetolian must have been mainly affiliated with animal husbandry due to the scarcity of arable lands. The rough land resulted in the locals' continuous movement in the search of more prosperous territories. Thucydides (c. 460/455 - 399/398 BCE) reports that the locals who had a sanctuary dedicated to Apollo at Thermos were organized in various tribal groups such as the Apodotoi, Ophioneis, Eurytanes, Agraioi, and the Aperantoi. The foundation of the temple is estimated before the first millennium BCE. The historian accused the Eurytanes of consuming raw meat, an idea that must have emerged due to the substandard agricultural conditions the non-urban tribes were living in. The interactions with the stronger forces of the period certainly stigmatized the area, as the Aetolians were a contender to be reckoned with.

Thucydides reported that, in 426 BCE, the citizens of Naupactus called the Athenian general Demosthenes to launch an attack on the Aetolian hillmen. In 367/366 BCE, there is a reference in an Athenian decree for the koinon (league) of the Aetolians. The date can indicate that the early 4th century BCE probably represents the period when the League was first established. The joint Aetolian tribes that proved enough to withstand the Athenian invasion of 426 BCE, could possibly resemble the early stages of the koinon. After Demosthenes' failed attack, Aetolian envoys were sent to Sparta and Corinth, seeking a broader union. These events led to a coalition of Aetolian and Spartan forces attempting to capture the city-state of Naupactus in the same year, although it eventually failed. The Aetolian antagonism for Naupactus continued until 369 BCE, but in due course, the Achaeans laid claim to the weakened city. Thus, the city continued to be guarded by the Achaeans until at least 338 BCE.

Growth

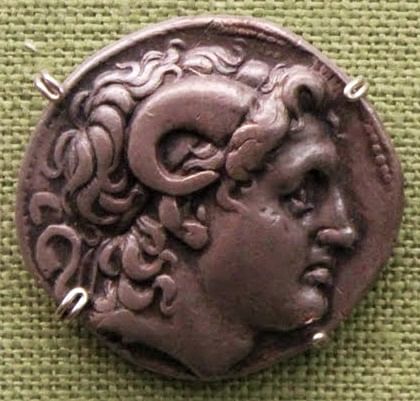

In 344 BCE, Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) reorganized the government of Thessaly, and one year later he placed his brother-in-law on the Molossian throne of Epirus. In 338 BCE, Philip delivered the city of Naupactus to the Aetolians, a strategy probably shaped by the outcome of the Battle of Chaeronea. However, Philip soon joined forces with the Achaeans to recapture Naupactus. Until Philip's death in 336 BCE and, according to Arrian (86 - c. 160 CE), the submission to Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), the League seems to have been subdued by the dominant powers. Plutarch (c. 45/50-120/125 CE) reveals that approximately in 330 BCE, the Aetolians captured the Akarnanian city of Oiniadai, without any known response by Macedon's temporary ruler Antipater (c. 399-319 BCE). Modern historians estimate that during this period Naupactus was reclaimed.

The death of Alexander in 323 BCE brought upheaval across the Macedonian Empire, and the Aetolians exploited the turn of events to ally with the anti-Macedonian Athenians. In 321 BCE, Antipater invaded Aetolia with a large force of 32,000 men. Once again the lightly-armed Aetolians, who, according to Diodorus, gathered a total force of 10,000 men, managed to withstand the invasion by fortifying the mountainous areas of their homeland. The Macedonian death toll was disastrous. Thus, a council of Macedonian strategoi decided to abandon Aetolia and face Perdiccas instead (d. 321 BCE). Until the end of the 4th century BCE, during the early phase of the Wars of Diadochi, the Aetolians managed to hold their position. While a series of unsuccessful attempts were made, like the storming of Thessalian territories in 321 BCE as Diodorus has claimed, they did not expand further.

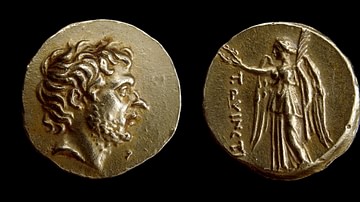

In 301 BCE, they allied with the Boeotians. By 293 BCE, Demetrius I had already captured Athens, sieged Thebes, and seized Phocis. The Aetolians did not support the assault on the Boeotian city. However, Demetrius' advance reveals a probable occupation or at least the protection of Delphi by the Aetolians, as Plutarch testifies to their blockade on the passes of Parnassus and Daulis in Phocis, which pointed to the sanctuary of Apollo. In 290 BCE, the Aetolians were accused by some of the Macedonian sympathizers in Athens of raiding Demetrius' supply lines. Furthermore, hostile actions against Macedonians would have continued until 289 BCE when Epirotian forces under the king Pyrrhus (c. 319-272 BCE), helped by Aetolian infantry, cut down the attacking forces in the northern soils of Aetolia. The Aetolians and Pyrrhus understood that to repel the Macedonian ruler, they had to join forces. Demetrius died in 287 BCE, with the Kingdom of Epirus dominating in the north, alongside Lysimachus (c. 361-281 BCE), one of Alexander's Diadochi (successors).

Strabo (c. 64 BCE to c. 24 CE) reveals the positive stance that the Macedonians, under the new ruler, had for the Aetolians, as later they named their cities Lysimachia and Arsinoe after Lysimachus and his queen. This favorable stance toward the Aetolians had to be grounded on the common interest and hate against Demetrius' son, Antigonus II Gonatas (c. 320-239 BCE). He received from his father resources and garrisons that threatened the eastern territories of Aetolia. Despite his wealth, Gonatas was unable to follow in the steps of his ancestors. With the domination of Pyrrhus in the west and Lysimachus to the north, the Aetolians were able to acquire new territories, and between 290 and 280 BCE, they managed to seize the bigger part of the shore of the Corinthian Gulf, the western section of Locris, as well as Herakleia in Trachis, a city north of Thermopylae. By 270 BCE the rest of Locris was incorporated into the league. Thus, in the early 3rd century BCE, the Aetolian League managed to expand to the Aegean Sea by establishing their presence in the Malian Gulf on the coasts of Phthiotis. Additionally, it dominated in the northern Corinthian Gulf while seeking infiltration into the Ambracian Gulf. The gulf was a broader territory that later contained the Roman colony Actium, where, in 31 BCE, the Battle of Actium between Octavian and Mark Antony took place.

The dominion of the already mentioned powers that surrounded Aetolia slowly started to shrink, as Phryrrus sailed to Italy in 280 BCE, Lysimachus died and lost his territories to Seleucus I Nicator (c. 358-281 BCE) in 281 BCE, and Antigonus I's forces diminished to a few cities and ships. The decline of power drew a series of Celtic invasions into the country. With Brennus as their leader, they raided Macedonia in 280 and 279 BCE. The Macedonians were forced to fortify their cities, thus, the northern invaders, having the paths freed of any significant opposition, moved southward to Thessaly. Subsequently, a Greek coalition was formed by several city-states, with the Aetolians and Boeotians representing the leading forces. The outcome of the two cultures' clash in Thermopylae revealed the Greeks as the victors. Later on, Brennus tried to divide the rival forces by raiding with a small force the Aetolian city of Kallion. However, their return was not as successful as their southward march, as Aetolian forces caught the Celts and, according to Pausanias (2nd century BCE), deprived them of half of their forces. Brennus' second attempt proved more efficient in the separation of the enemy forces as he aimed to raid the sanctuary of Delphi. The historian testifies that a small force of Phocians, Amphissans, and Aetolians kept the 'barbarians' busy until a bigger Aetolian force of more than a thousand troops defeated Brennus' Celts.

The Chremonidean War of 267-261 BCE, which was fought between Antigonid Macedonia and a coalition of Greek city-states and the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt, diminished even further the leading Greek city-states' forces. It concluded in a Macedonian triumph, cementing Antigonid hegemony over the Greek city-states. Aetolia managed not to participate in the clash and exploited the other's weaknesses to incorporate Malis. Thus, Aetolia shared its border with Boeotia in the east, Thessaly in the north, and Akarnania in the west, and the leaders of the League probably managed to uphold a relatively peaceful existence in their territories until 239 BCE.

Downfall

Gonatas' death in 239 BCE, which led to Demetrius II's (275-229 BCE) ascension to the throne, signified a new policy toward Aetolia. According to Polybius, shortly after his official succession, he invaded Boeotia, probably through the Macedonian Chalcis in Euboea and the Aetolian territories of Malis and Thermopylae in 236/7 BCE, and allied with the local ruling class. Moreover, through marriage, he allied himself with the kingdom of Epirus. That is why the Aetolian League responded to the external pressures by cooperating with the Achaean League. Demetrius' death in 229 BCE concluded the scarcity of direct assaults between Aetolia and Macedon, as there were no documented attacks between the two rivals.

The new king of Macedonia, Antigonus III Doson (229-222 BCE), followed a different policy toward his southern Aetolian neighbors. In 228/7 BCE, he probably negotiated a peace treaty that divided Thessaly among the two powers. In the next few months friendly relationships must have developed between the Aetolians and the Cephallenians in 224 BCE, when, according to the colonial law from Thermos, an Aetolian colony was established in the island of the Ionian Sea, in the city of Same. This alliance represented a countermeasure against the Illyrian raids on the western coasts. Additionally, this agreement would have added an allied Cephalonian naval force to the unsubstantial Aetolian maritime squads. In 221 BCE, Doson died, and Philip V (221-179 BCE) ascended to the throne. The king continued controlling his predecessor's Symmachy (alliance) between Akarnanian, Epirus, Thessaly, Phocis, Boeotia, and Macedon, which was held from 223/2 BCE. Polybius testified that Aratos of Sicyon (271-213 BCE), the leader of the Achaean League, urged the Macedonians in the Symmachy's assembly at Corinth to declare war against the recently acquired Aetolian territories.

The Aetolian League managed to acquire the support of Sparta and Elis for the upcoming war against the Symmachy. The Macedonian hegemon (leader) with a force of over 20,000 men captured the Aetolian Ambracus, a port in the Ambracian Gulf. The response was an even more rapid Aetolian raid by the strategos Scopas (d. 196 BCE) in southern Macedonia at the ancestral city of Dion. He hoped to distract the Macedonian forces, but, considering that Philip moved deeper into Akarnania with an extra 2,000 Akarnanian troops and attacked the last few cities that maintained ties with the League, Scopas' plan turned out to be unsuccessful. Furthermore, Philip moved further into Kalydon and captured Oiniadai. However, a probable invasion of northern Macedonian borders by the Dardanians drew Philip away. He placed a substantial garrison in Larisa to protect further violent Aetolian claims. After September of 219 BCE, Dorimachus the newly elected strategos raided the territories of Epirus probably as a retaliation for the past events of Ambracus, and according again to the apparently exclusive narrator Polybius, captured the sanctuary of Dodona in Epirus.

The Aetolian general Euripidas, who was partially responsible for the earlier attacks against the Achaean League, continued the advance in Peloponnese until his forced retreat in 218 BCE when Philip intercepted the meager Aetolian forces with his vast Macedonian army. Polybius attested that Philip needed only six days to restrain the Aetolian position in Peloponnese. On the opposite front, Dorimachus was preparing for an invasion of Thessaly. Philip took the Aetolian fightback by Dorimachus as an opportunity to raid the religious center of Aetolia at Thermos. In 217 BCE, the hegemon, after returning to Macedonia to recruit new forces, met the Aetolian in the southern borders of Thessaly and captured the Aetolian base of Phthiotic Thebes, the center of the Thessalian raids. He sold its population and installed a Macedonian colony instead, named Philippi. Finally, after the Macedonians marched and camped across Naupactus, the Aetolians agreed to a peace treaty with Philip. Nevertheless, the following Roman intervention caused four devastating Macedonian Wars in the Greek mainland that included a fatal Aetolian involvement.

Rome's clash with Hannibal, during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) and Philip's probable alliance with Carthage commenced the First Macedonian War (214-205 BCE) and brought Rome into Greece's geopolitical interplay. Furthermore, Thessaly was planned to be evacuated in 197 BCE after Roman general Titus Quinctius Flamininus (c. 228-174 BCE) exploited the Macedonian leader's lack of strength compared to the mighty Roman Republic. His demand was rejected by Philip, and the war was prolonged. In the same year, the two armies collided in Thessaly at the Battle of Cynoscephalae, where the Macedonians were defeated. Moreover, the Aetolians attempted to gain more self-sufficiency out of fear of the Romans' totalitarian intentions and invited Antiochus III the Great (c. 241-187 BCE), ruler of the Seleucid Empire, to assist them. However, during the Roman-Seleucid War (192-188 BCE), the Romans defeated the Seleucids and made the Aetolians pay the price by pillaging the stronghold of Ambracus in 189 BCE. Eventually, the Aetolian mainland was considerably diminished during the Third Macedonian War (172-168 BCE). Aetolia's influence significantly declined following the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BCE) as a result of being incorporated into Rome's newly established province of Macedonia.