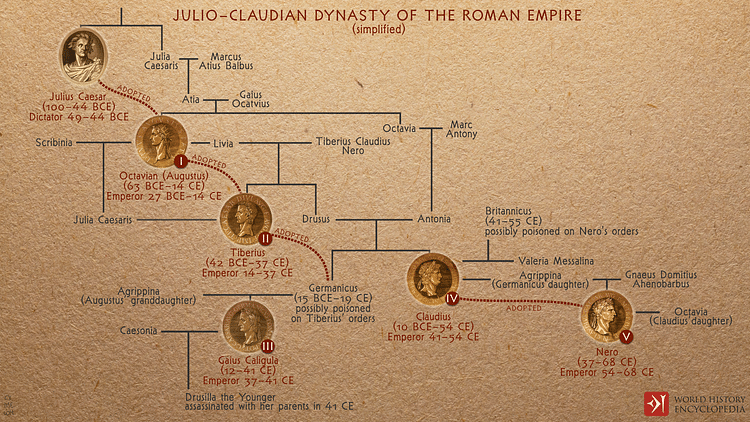

Julia Agrippina or Agrippina the Younger (6 November 15 - 19/23 March 59 CE) was a prominent woman during the early Roman Empire, niece to Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) and Claudius (41-54 CE), whom she married, sister of Caligula (r. 37-41 CE) and mother of Nero (54-68 CE). She attempted to manipulate her young, inexperienced son; however, Nero soon became suspicious of her mother's growing influence, and after removing her from the imperial palace, he had her killed in an unclear way.

Early Life

Agrippina was born on 6 November 15 CE, at Oppidia Ubiorum (later renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium at Agrippina's own request) in modern-day Germany. Her parents were Germanicus, the nephew of the ruling Roman emperor Tiberius, and Agrippina the Elder, daughter of Marcus Agrippa and Augustus' daughter, Julia. She had eight siblings, but only five of them survived infancy: among them was the future emperor Caligula.

She spent her early life in Rome while her parents were in the provinces; Germanicus died in Antioch in 19 CE. He may have died due to illness, but many people suspected that the reclusive emperor Tiberius was behind his death. Agrippina the Elder started advocating the rights of her own family and, while, at first, she may have been just a nuisance to Tiberius, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Sejanus recognized Agrippina was a danger to his own influence and turned the emperor against her. Agrippina the Elder and her two oldest male children were also exiled and imprisoned; they were all dead by 33 CE. Meanwhile, the young Agrippina, a girl who was no threat to the emperor, was allowed to marry Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus in Rome in 28 CE. The groom came from a prestigious family of consular rank, linked to Augustus through Domitius' mother, Antonia the Elder, the first daughter of Octavia, Augustus' sister. Octavia's other daughter, Antonia the Younger, was Agrippina's grandmother, making the two newlyweds related.

Caligula's Reign

In his last years, after Sejanus' execution on account of treachery, Tiberius adopted the youngest son of Germanicus, named Gaius and nicknamed Caligula. Tiberius died in 37 CE, and it was in that year that Agrippina the Younger gave birth to her only son, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, the future Nero. The new emperor, Caligula, bestowed various honours on his three sisters, Drusilla, Livilla, and Agrippina, for example, their names were included in oaths and they could sit with the emperor himself at games. The close relationship Caligula had with his three sisters is attested by some of his early coinage, which would show the three women of the reverse. Suetonius claims that ''he lived in habitual incest with all his sisters, and at a large banquet he placed each of them in turn below him, while his wife reclined above'' (Life of Caligula, 24.1); this, however, is likely just a fabrication.

Drusilla died in 38 CE, possibly due to a fever, and consequently, her husband Lepidus, who was looked upon as Caligula's successor, lost his prestige and started plotting with the two surviving sisters against the emperor. Caligula's erratic, provocative, and arrogant behaviour had alienated the Senate, and the sisters saw Lepidus as their potential protector. Details are unclear; the plot, however, failed. Lepidus was promptly executed, while Livilla and Agrippina were accused of adultery and forced into exile. Agrippina was still in exile when her husband died two years later; their son, young Lucius, stayed in Rome with his aunt, Domitia Lepida.

Marriage to Claudius

Caligula was assassinated in early 41 CE. His successor and uncle, Claudius, recalled Agrippina and Livilla back from the exile. While the latter was executed by the emperor a few years later, maybe due to the scheming of Claudius' wife Messalina, Agrippina started looking for a new husband. She made advances to the future emperor Galba (r. 68-69 CE), who was married and refused her - it is reported Agrippina was also slapped by Galba's mother-in-law for her behaviour. In the end, she married the newly divorced uncle of Lucius, Passienus Crispus, who was also a descendant of the historian Sallust. He was a wealthy orator and ensured Agrippina enough protection while young Lucius was growing. In 47 CE, however, Crispus died, and Agrippina inherited his immense wealth - Suetonius suggests Agrippina herself poisoned him but, as usual, this cannot be proven.

A year later Messalina was executed, and Claudius declared he did not intend to marry again. However, Pallas, one of Claudius' influential freedmen, convinced the emperor to marry his own niece Agrippina. Since they were closely related, the Roman Senate passed a special law to allow Claudius to marry Agrippina. The motivations behind the marriage are unclear, but the ageing emperor ended up adopting Agrippina's son, who was given a new name, Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, and became commonly known as Nero. The tie between Claudius and Agrippina was further strengthened by the marriage of Nero and Octavia, Claudius' daughter with Messalina. Tacitus suggests that it was Agrippina who manipulated Claudius into making Nero his heir, however, the choice may have seemed sensible to Claudius since his biological son, Tiberius Britannicus, was younger than Nero and suffered from epilepsy.

Agrippina became more and more prominent during Claudius' reign. She was granted the title of Augusta - the last living woman to have received the title was Augustus' wife, Livia Drusilla, and even she had to wait for her husband's death. Agrippina was one of her husband's most trusted advisors. Pliny the Elder notes that she sat next to Claudius during the games intended to celebrate the drainage of the Fucine Lake, '"attired in a military scarf made entirely of woven gold without any other material" (Natural History, XXXIII.19); she was also there when Claudius received the defeated British chieftain Caractacus in Rome. Tacitus, however, also notes her tyrannical behaviour, which led to the death of many figures closely related to Nero, such as Domitia Lepida, who had looked after him during Agrippina's exile. As fierce she may have been, she convinced Claudius to recall Seneca (4 BCE - 65 CE) from his exile - the emperor had exiled him earlier in his reign - and put Nero under his watch, along with the newly nominated praetorian prefect Afranius Burrus.

Nero & Death

Aged 63, Claudius died in 54 CE. Tacitus, Cassius Dio, and Suetonius are convinced Agrippina poisoned him because the emperor had started to have second thoughts about Britannicus and Nero's positions, but that cannot be proven. What we know for certain is that Agrippina had Narcissus, one of Claudius' most influential freedmen and one of her enemies, imprisoned and executed soon after Claudius' death. Nero succeeded Claudius with no opposition; the late emperor was extremely hated by the Senate and so the accession of young Nero was considered the start of a new, golden age. Agrippina, as the mother of the new emperor, became more and more prominent; she even started appearing on the obverse of some coins along with the emperor himself. The power and influence Agrippina had reached were unprecedented for a woman; however, that was to change very soon.

For a start, Nero did not like Octavia and preferred the freedwoman Claudia Acte over her; this was unacceptable to Agrippina, who saw the marriage as an act of legitimacy. Seneca and Burrus did not help either; they started undermining Agrippina's influence for their own profit. Pallas, Agrippina's main supporter, was also removed from the court. Despite all this, Agrippina tried to hold onto power, and according to Tacitus she even ''presented herself on several occasions to her half-tipsy son, coquettishly dressed and prepared for incest'' (Annals, XIV.2). Whatever the case, Agrippina's image keeps showing up on coins until at least 57 CE. However, a power struggle between Agrippina and Nero's tutors for the influence over the young emperor does not sound too far-fetched. Apparently, Agrippina, seeing how her influence was fading away, started to associate herself with Britannicus; the boy, however, died in 55 CE, maybe poisoned by Nero or maybe due to an epileptic attack. Not long afterwards, Agrippina was removed from the court.

Even though Agrippina was no longer at court, she retained her influence due to her family connections and her illustrious father Germanicus. Nero had good reasons to fear her, especially because she could have married one of Nero's rivals, Rubellius Plautus, starting a civil war. The emperor decided to eliminate the potential threat by matricide. Tacitus suggests that Nero wanted to get rid of Agrippina because she did not approve of his marriage to Poppaea Sabina. This, however, seems unlikely, since Nero only married Poppaea in 62 CE, well after Agrippina's death.

Details of Agrippina's murder are recorded by Tacitus and Cassius Dio: according to them, in 59 CE, Nero told his mother that he wanted to reconcile with her during the Quinquatriae festival. While Agrippina was returning to her villa, her boat sunk in a premeditated accident. Agrippina managed to save herself, but Nero sent his Praefectus classis (fleet commander) to finish her off. Allegedly, Agrippina told her executioner to strike her womb that had produced her own murderer. This version is likely a fabrication, and while the exact details of Agrippina's final demise are unclear, it is possible that Nero caught her plotting against him and she committed suicide.