Thera is the ancient name for both the island of Santorini in the Greek Cyclades and the name of the volcano which famously erupted on the island in the middle Bronze Age. The 17th century BCE eruption covered Akrotiri, the most important settlement, in a layer of pumice and volcanic ash, thereby perfectly preserving the Bronze Age town.

Early Settlement

The earliest evidence of settlement on the island at Akrotiri (named after the nearby modern village) dates back to the mid-fifth millennium BCE when a small fishing and farming community established itself on a coastal promontory. By the third millennium BCE the presence of rock-cut burial chambers, pottery and stone vases and figurines suggest a period of significant growth. The marble used for these vessels probably came from the nearby islands of Paros and Naxos and together with finds of Theran pumice stone (used as a polish abrasive) suggest the presence of inter-island trade. Wood and food goods were also probably exchanged at this time, not only throughout the Cyclades but also with the Greek mainland and Crete.

Around 2000 BCE the settlement expanded further, and a disused cemetery was filled and constructed upon - both the fill containing pottery shards from large amphorae and black/brown burnished pottery (Kastri style) finds suggest healthy Aegean trade relations were in existence. Being strategically well-placed on the copper trade route between Cyprus and Minoan Crete, Akrotiri also became an important centre for metal work, as is evidenced by finds of moulds and crucibles.

Urbanisation & Disaster

From 2000 to 1650 BCE Akrotiri became more urbanised with paved streets and extensive drainage systems. Quality pottery was mass produced and decorated with lines, plants and animals. Metallurgy and other crafts (particularly those related to the maritime industries) became more specialised. In this period there is also evidence of repair and rebuilding projects following earthquake destruction.

Akrotiri's prosperity came to a sudden end in the 17th century BCE with the massive and cataclysmic eruption of the island's volcano. Preceded by earthquakes of a magnitude of 7 on the Richter scale which destroyed the town and created 9m high tidal waves, the eruption itself probably occurred a few days later and released an estimated 15 billion tons of magma into the atmosphere, making it the largest volcanic eruption of the last 10,000 years. The entire island was buried in a thick layer of ash, Trianda on Rhodes was destroyed, 7cm of ash covered sites in northern Crete, Anatolia suffered from the ash fall-out and even ice-cores in Greenland demonstrate the far-reaching effects of the eruption. The precise date of the event is much debated amongst scholars with wildly different estimates vigorously defended in order to support various hypotheses for other events such as the destruction of Minoan palaces or Mycenaean imperialistic ambitions in the Aegean. The most agreed upon date ranges somewhere between 1650 and 1550 BCE (with ice-core studies and radiocarbon dates suggesting the earlier date).

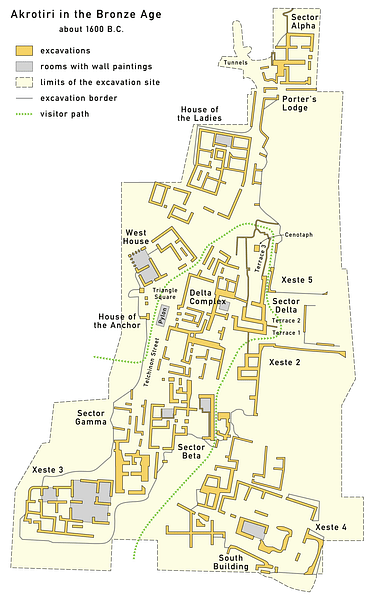

Following the cataclysmic volcanic event, the town of Akrotiri was completely covered in volcanic ash and thereby remained extremely well preserved; for example, through negative casting it has been possible to identify usually perishable items such as wooden furniture, most commonly stools and beds. However, unlike at Pompeii where life seems frozen by the disastrous eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, at Akrotiri there were no human remains of casualties found at the site and there is evidence of some attempt to clear rubble which suggests that there was a short gap between the earthquakes and the eruption and many residents had already abandoned the town before the final cataclysm. The site remained hidden from sight until its systematic excavation from 1967 CE.

The well-planned town has squares and wide streets. Buildings were of two or three stories with flat roofs supported by a central wooden column. Architectural features in common with those in the Minoan civilization include a large hall, lustral basins, ashlar masonry, horns of consecration and the occasional lightwell.

Architecture & Art

Interestingly, almost all of the buildings excavated at Akrotiri have scenes painted on the interior walls in one or more of their rooms, illustrating that it was not only the elite who had such artwork in their homes. Fresco subjects and style were much influenced by the Minoan civilization - religious processions, goddesses, lilies, crocuses etc. and by the later Mycenaean civilization on the Greek mainland - griffins and boars' tusks helmets. More local themes such as girls gathering saffron, seascapes and fishing activities were also popular as were exotic animals such as antelopes and monkeys. Many rooms were completely covered in painted depictions of landscape scenes attesting to a love of nature and creating a powerful visual impact which transports the viewer beyond the confines of the room.

In addition to Fresco subject matter, other finds such as Cretan and Mycenaean pottery, seal impressions using Minoan iconography, Minoan clay loom weights, Canaanite jars, the use of the Minoan Linear A script and items of Egyptian origin (e.g.: ivory and ostrich eggshells) attest to Akrotiri's continued importance as an important trading centre with contacts throughout the Aegean.

Although the date of the event is difficult to fix, the effect of the disaster is clearly evident in physical archaeological remains but also in more intangible terms. It has been suggested that the eruption of Thera may be the origin of the Atlantis myth - the destruction of an island and with it the loss of an advanced civilization. From the point of view of Greeks in the so-called Dark Ages (from c. 1100 BCE) the Minoan/Mycenaean-influenced community on Thera may well have appeared as a golden age, a time when cultural and artistic achievements were greater than in the present time but in just a few days consigned to history by Nature's whim.