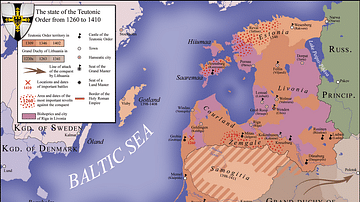

The Albigensian Crusade (aka Cathars' Crusade, 1209-1229 CE), was the first crusade to specifically target heretic Christians - the Cathars of southern France. Not successful in repressing the heresy, the on-off campaigns over two decades, led by Simon IV de Montfort, did achieve their real purpose: the political annexation of the Languedoc region, eventually bringing it under the control of the French Crown. The Crusade set a precedent for attacking fellow Christians which would be repeated in Germany, Bosnia and the Baltic regions.

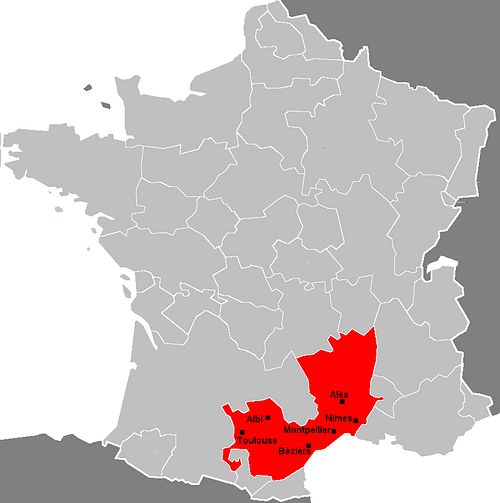

Languedoc & the Cathars

Medieval Languedoc was a region of southern France with its unofficial capital at Toulouse. The literary language there was Occitan, which gave its name to the wider cultural region of southern France, Occitania, of which Languedoc was a part. The Albigensian Crusade directed against this region in the first quarter of the 13th century CE takes its name from Albi, the cathedral city 65 kilometres north-east of Toulouse. Albigensian means 'from Albi' but the heretics are more accurately known as the Cathars of Languedoc, even if their first important centre was established at Albi.

The region of Languedoc was a stronghold of the Cathars, a group of heretics who sought to promote their own ideas regarding the age-old problem of how the Christian God, a Good God, could create a material world which contained evil. Their name derives from katharos, the Greek word for 'clean' or 'pure' and they probably derived from the more moderate Bogomil heretics of Byzantine Bulgaria. The Cathars, who were also present in Lombardy, the Rhineland and Champagne regions, believed that there were two principles of Good and Evil, a dualist position that was not new and had been promoted by such groups as the 7th century CE Paulicians. The Cathars believed that an evil force (either a fallen angel - Satan - or an eternal evil god) had created the material world while God was responsible for the spiritual world. Humanity must, as a consequence of this evil, find a way to escape their material bodies and join the pure Good of the spiritual world. As the two worlds were entirely separate, the Cathars did not believe that God had appeared on earth as Jesus Christ and had been crucified.

The Cathars, wary of materialism, lived in isolated communities with the minimum of comforts, although there were two degrees of active participation with one being stricter and its adherents confined to monasteries. The Cathars were by no means the only religious group in the Languedoc region and the Catholic Church was an ever-present fixture of society too, but by the early 13th century CE, it was the Cathars, with their own churches, bishops and followers of all social classes, who posed the most dangerous threat to the authority of the Catholic Church in France. Accordingly, it was this specific group that the Papacy sent an army to deal with between 1178 and 1181 CE. The meagre result of this campaign was a few conversions and promises for reform but, by the first decade of the 1200s CE, it was clear that many of the Languedoc lords were still supporting the Cathars as a less expensive alternative to the tax-loving Catholic authorities. Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE), after an unsuccessful preaching campaign by his legates, decided it was time to eradicate the heretics by force. The final straw had been the murder of a Papal legate near Arles in 1208 CE, the deed done by a servant of the most powerful Languedoc lord, Count Raymond VI of Toulouse (r. 1194-1222 CE).

Popes & Kings

Pope Innocent III awarded the campaign against heretics Crusade status, which meant that Church funds could be directed towards its fulfilment and those who fought in it were guaranteed a redemption of their sins like the crusaders in the Holy Land. It was the first crusade to specifically target Christians and not Muslims, even though the Fourth Crusade (1202-04 CE), also called by Innocent III, had ended up sacking Christian Constantinople which had not been the initial aim of the Crusade. It was also the first time that the Church called on an international force of warriors to battle heretics; previously such attacks had been conducted only on a local level. The idea of attacking fellow Christians gained ground thanks to such figures as Saint Mary of Oignies who claimed to have had a vision in which Jesus Christ expressed his concern at the heresy in southern France, and Saint Mary even travelled herself to the region. What was needed next was political support to match the ecclesiastical arguments for attacking southern France.

Following an appeal from Innocent III and the excommunication of Raymond VI of Toulouse, the proposed campaign was supported by the French king Philip II (r. 1180-1223 CE) and his son, (the future) Louis VIII (r. 1223-1226 CE) as a means to increase the control of the crown over southern France - at that time a region more in sympathy with the kingdoms of eastern Spain. Indeed, the Cathars were only present in a small area of southern France so that a religious justification for the campaigns was perhaps only really an excuse in the process of forming the kingdom of France and giving its king direct access to the Mediterranean. Accordingly, with the backing of the Church and Crown, and the promise that the lands of defeated barons would be confiscated, taxes were raised in northern and central France and an army assembled in 1209 CE. Although the French king was too preoccupied with his rivalry with King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE), he did supply a royal contingent and there were such noted leaders as Simon IV de Montfort and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria (r. 1198-1230 CE).

War: Simon de Montfort

As the Crusader army left Lyons and moved down the Rhône River in July 1209 CE the first snag was encountered. Raymond of Toulouse, the figurehead of the enemy at least in propaganda terms, had opened up negotiations with the Pope and, after a suitable penance and giving up a spot of land, he joined the Crusader army as an ally. Accordingly, the first target of the crusaders was to attack not Toulouse but the area around Albi controlled by Raymond Roger Trencavel in 1209 CE. Trencavel was not a heretic but his lands contained a good many of them. The Crusaders were led by Simon IV de Montfort, a man of experience who had already campaigned with success in the region two years previously against the armies of Raymond of Toulouse. Now Simon had the Church's backing for his ambitious conquest. Besides the armies of nobles and knights on both sides, there were, too, local militias, the White Confraternity against the heretics and the Black Confraternity supporting the local barons.

Ultimately, the weak political unity of the southern lords and their own tradition of fierce independence meant that the Crusader army won victory after victory, even if the latter had its own problems in keeping men in the field for what seemed little gain for themselves except a spiritual one. Indeed, the Pope had to insist that only a minimum 40-day military service would ensure a full remission of sins by participants. The campaign was, thus, sporadic and brutal. It became a long-drawn-out affair characterised by lengthy sieges not helped by a chronic lack of money on the part of De Montfort, and the slipping away of crusaders every 40 days.

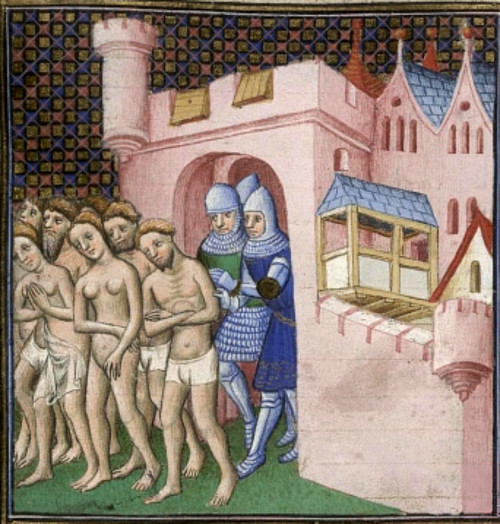

The first major action was when Raymond Roger Trencavel abandoned Béziers on 21 July 1209 CE. The city was besieged by the crusaders anyway and, after the offer of a truce if any heretics were handed over was rejected, the city was ruthlessly sacked. The city's inhabitants, around 10,000 people, were slaughtered in cold blood. The city had probably only had some 700 heretics and it was now clear to all that this was a campaign of conquest, not conversion. Such was the shock of the massacre that the city of Narbonne surrendered immediately and locals fled any castles and towns likely to be the next target of a crusader attack. The mighty castle of Carcassonne fell on 14 August 1209 CE and Trencavel was put in a prison from which he would not escape alive. Simon de Montfort took over Trencavel's lands.

More atrocities would follow on both sides. When Lavaur was captured by De Montfort in 1211 CE Aimery, the lord of Lavaur and Montréal, was hanged, his sister was thrown into a well, 80 of his knights were executed and up to 400 Cathars were burned to death. For captured heretics, a trial and death by fire was their usual fate. Significantly, though, many of the crusader targets were not Cathar strongholds. The whole region developed into a perpetual war zone with a consequent collapse in the rule of law and social order. In 1211 CE the crisis deepened when Raymond of Toulouse decided the crusaders were making too many demands on his territory and he made himself enemy number one again by going independent once more.

After defeating a Toulouse-Foix army at Castelnaudary in September 1211 CE, De Montfort captured large areas of the south in 1212 CE. Raymond, meanwhile temporarily fled to England. Although northern France was instigating plans of government in the region, by 1213 CE guerrilla warfare had spread everywhere in the south. The massacres, burnings and mutilations continued whenever a town or castle was captured. As a consequence, the Pope cancelled the Crusade status of the campaign but it would be given again, albeit sporadically over the next 15 years. In 1214 CE the turmoil even brought foreign kings sniffing with interest at the choicest lands as they became available, notably the King of Aragon and King John of England who still had lands in France.

By 1215 CE the conquest of the County of Toulouse and the Pyrenean counties was complete and Crown Prince Louis even did a tour with an army that never did any battle. Then there came a local fightback, the defenders being greatly helped by the return of Raymond to his stronghold at Toulouse in 1217 CE. The Crusade was dealt another blow with the death of De Montfort during the siege of that city in June 1218 CE; he was killed instantly when he was hit by a boulder fired from a mangonel catapult. Louis took over De Montfort's territorial claims and made another brief appearance in the south, capturing Marmande in June 1219 CE.

The war rumbled on at a local level, now primarily conducted by allies of Toulouse and those barons who had gained their lands from De Montfort. Raymond of Toulouse died in 1222 CE and he was succeeded by his son Raymond VII (r. 1222-1249 CE), who reclaimed much of his father's old lands and even Carcassonne in 1224 CE. Louis, now king Louis VIII after his father's death in 1223 CE, was determined to expand his kingdom, though, and with the backing of Pope Honorius III (r. 1216-1227 CE), another crusade was launched with all the Papal trimmings. Avignon was besieged and captured in the summer of 1226 CE. Realising the inevitable, most Languedoc lords swore homage to the king but Raymond VII held out. Then, returning to Paris in November 1226 CE, Louis VIII died of dysentery.

The new king of France, Louis IX (r. 1226-1270 CE), would turn out to be one of the most committed of all medieval Crusader kings and so the Albigensian campaign was an ideal tester for the religious zeal that would eventually earn him sainthood. A series of victories came in the next two years and Raymond VII of Toulouse agreed terms of surrender. The Albigensian Crusade thus came to a final conclusion with the Treaty of Paris in 1229 CE. The Languedoc region was now part of the Kingdom of France.

Aftermath

The campaigns had dramatically reduced the wealth and power of the Languedoc nobility and the re-shaping of the royal political map was nicely completed when Raymond VII's estates passed on to his heir, Alphonse of Poitiers, brother of Louis IX, in 1249 CE. The Cathars, meanwhile, were not wiped out and their churches and institutions continued in the region, albeit on a reduced scale. An Inquisition was launched but its aim was to convert through argument, not violence; one of its effects being the establishment of a university at Toulouse in 1229 CE. This intellectual approach was slower but far more successful than the Crusades and by the first quarter of 14th century CE the Cathars ceased to exist as an organised and distinct body of believers.

Reflecting the ambiguity of the Albigensian Crusade and the uncomfortable truth of Christians fighting Christians, some popular songs of the period criticised the Popes for granting the campaign a Crusade status and its participants a remission of sins. For example, as Guilhem Figueira's 13th century CE sirventes song goes:

Rome, in truth I know, without a doubt, that with the fraud of a false pardon you delivered up the barons of France to torment far from Paradise, and, Rome, you killed the good king of France by luring him far away from Paris with your false preaching. (quoted in Riley-Smith, 111)

There has also developed a certain nostalgia and historical myth-making regarding the Albigensian Crusade with southern French people sometimes using the episode as an example of their cultural independence from an overbearing northern France epitomised by the central government in Paris. The heretics have also appealed to the modern mind with their vegetarianism and improved role for women but these facets of culture are to ignore the fact that there were atrocities and bigotry on both sides during the Crusade which began the process of western Christians fighting each other, a situation that would blight European politics and society for centuries thereafter.