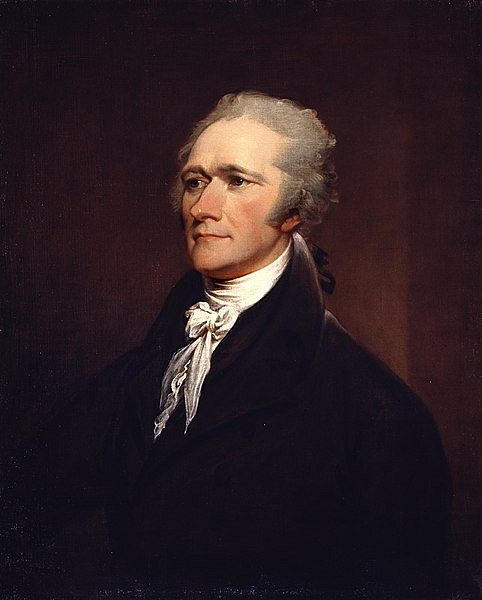

Alexander Hamilton (1755/57-1804) was a lawyer and politician, often recognized as a Founding Father of the United States. He served as George Washington's aide-de-camp during the American Revolution, before going on to become the first US secretary of the treasury and a leader of the Federalist Party. He was mortally wounded in a duel with Aaron Burr in July 1804.

Early Life

Alexander Hamilton was born on the small island of Nevis in the British West Indies on 11 January 1755 or 1757; most modern scholars favor 1755 as his birth year, based on the discovery of a 1768 probate paper that listed his age as 13. He and his older brother, James, Jr., were born out of wedlock to James Hamilton, the wayward younger son of a Scottish laird, and Rachel Faucette Lavien, a married woman who had abandoned her husband after years of unhappy marriage. The couple lived together for several years until 1765, when James Hamilton abruptly deserted his family, either because he had run out of money or because he knew his continued presence would leave the still-married Rachel vulnerable to charges of bigamy. In any case, Rachel was left destitute. To provide for her sons, she opened a modest shop on St. Croix, purchasing her merchandise from her landlord. In early 1768, both Rachel and Alexander contracted yellow fever; while the boy soon recovered, the mother succumbed to the disease on 19 February.

The orphaned Hamilton brothers were sent to live with a cousin, Peter Lytton, but this situation would end after only a year when Lytton committed suicide. The brothers were then split up; James, Jr., was apprenticed to a carpenter, while Alexander found work clerking for the merchant house of Beekman and Cruger. Still only a teenager, Hamilton excelled at his various tasks, which included tracking cargo, helping to chart courses for ships, and calculating prices in multiple currencies. In 1771, he was even left in charge of the firm for five months while the owner was away. Hamilton was a voracious reader who aspired to write works of his own and penned several poems in the early 1770s. In the autumn of 1772, he wrote a letter to his father in which he detailed a hurricane that had recently devastated St. Croix. The letter found its way into publication in a local paper, the Royal Danish-American Gazette, leaving readers dazzled with its vivid and bombastic descriptions:

It seemed as if a total dissolution of nature was taking place. The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about it in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed, were sufficient to strike astonishment into the angels.

(quoted in Chernow, 37)

This essay would prove to be one of the most consequential of Hamilton's life; upon learning that its author was only 17, local community leaders pooled their funds to send the promising young man to college in North America. He landed in Boston in October 1772, before going on to New York City, where he would enroll in King's College (present-day Columbia University) the following year. Hamilton was insatiably ambitious and dove into his studies, which included a classical curriculum of Greek and Latin as well as rhetoric, history, mathematics, and science. His academic career would soon be interrupted, however, by the rising tensions between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies over the question of American liberties, particularly that of taxation without representation. Hamilton became swept up in the Whig (or Patriot) movement, writing a series of anonymous pamphlets in which he defended the Boston Tea Party, supported the actions of the First Continental Congress, and condemned Parliament's Intolerable Acts. He opposed the mob violence often displayed by fellow Patriots; on 10 May 1775, he saved the college's Loyalist president, Myles Cooper, from an angry mob by speaking to the crowd long enough to allow Cooper to escape.

Revolutionary War

Shortly after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775, Hamilton joined with other King's College students to form a Patriot militia company; initially called 'the Corsicans' in reference to the Corsican Republic, the company eventually settled on the name 'Hearts of Oak'. When, in August 1775, the British warship HMS Asia appeared off the coast of Manhattan, Hamilton and other 'Hearts of Oak' seized ten British cannons from the Battery at the southern tip of the island and returned fire. The following year, the 'Hearts of Oak' were incorporated into a new artillery company of the Continental Army, with Hamilton elected as their captain. The company saw action at the battles of Harlem Heights and White Plains and acted as a rearguard during the army's subsequent retreat through Manhattan and New Jersey. In one instance, Hamilton's artillery unleashed a 'smart cannonade' that delayed the pursuing British troops from following the Continental Army across the Raritan River. During the Battle of Princeton, his cannons bombarded a group of British soldiers who had taken shelter in Nassau Hall, forcing their surrender.

Hamilton's conduct earned him the attention of the army's commander-in-chief, General George Washington, who invited the young officer to join his staff as aide-de-camp on 20 January 1777. Hamilton accepted the appointment, which came with a promotion to lieutenant colonel. For the next four years, he devoted his tireless energy to writing letters to generals and politicians, conveying Washington's orders to the troops, and acting as a liaison between American and French officers. He was with the army during the bitter winter at Valley Forge and remained fiercely loyal to Washington during the Conway Cabal. During this time, Hamilton developed close friendships with two other young officers, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette and John Laurens. Hamilton and Laurens formed an especially intimate bond, with some scholars detecting homoerotic undertones in their correspondence; Hamilton's own son would one day write that a "tenderness of feminine attachment" existed between the two men (Chernow, 95). Certainly, Hamilton was deeply affected by Laurens' death in a minor skirmish in 1782 and never again formed a friendship so intimate.

Whatever the nature of his relationship with Laurens, Hamilton was certainly fond of women; biographer Ron Chernow writes that he often "tended to grow flirtatious, almost giddy, with women" (93). He courted Catherine Livingston, daughter of the former New Jersey governor, before meeting the pretty and charming Elizabeth Schuyler while stationed at Morristown in late 1779. He was instantly smitten with the young woman; the fact that she was the daughter of General Philip Schuyler, one of the most influential men in New York, would have made her more attractive to the ambitious Hamilton. They were married on 14 December 1780 and would ultimately have eight children. By then, Hamilton had become one of Washington's most trusted advisors but was growing restless with desk work and longed for the glory of a field command. He would get his chance on 14 October 1781, during the final days of the Siege of Yorktown, when he led 400 men in a daring assault on the British troops in Redoubt No. 10. He took the redoubt with minimal casualties, contributing to the surrender of the British army five days later.

Early Politics & Federalist Papers

After the victory at Yorktown, the war was all but won, with the United States securing its independence two years later in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Hamilton resigned his army commission and went to Albany, New York, to study law, and he was admitted to the bar in July 1782. That November, he was sent to the Confederation Congress as a representative from New York, serving until July 1783. During his tenure in Congress, Hamilton became embittered with the Articles of Confederation, which deliberately kept the federal government weak to preserve the sovereignty of the states. Hamilton strongly believed that the Union would unravel unless the federal government were strengthened. In September 1786, at the Annapolis Convention, Hamilton drafted a resolution urging that the Articles be amended, if not replaced. This led to the Constitutional Convention, which met in Philadelphia in May 1787.

Hamilton attended the convention as one of the three delegates from New York. He ended up having little impact on the convention, with his major contribution being a long speech on 18 June in which he spoke in favor of elective monarchy. The convention resulted in the United States Constitution which did indeed strengthen the national government, although it did not go as far as Hamilton would have liked. Nevertheless, he signed the Constitution on 17 September 1787. The road to ratification would not be easy, as many Americans were still skeptical of giving too much power to a central authority. To help win them over, Hamilton began writing a series of pro-ratification essays under the pseudonym 'Publius'. He recruited two collaborators, James Madison and John Jay, and together they wrote 85 essays between October 1787 and May 1788. Hamilton wrote 51 of these essays, known as the Federalist Papers, himself. These essays were widely read at the time and have become regarded as some of the most important writings in US political history.

Treasury Secretary

The US Constitution was ratified by the necessary nine states and went into effect in March 1789, with Washington unanimously elected as the first president. On 11 September 1789, Hamilton was appointed as secretary of the treasury and came to the office with grand visions for the future of the country. He saw himself as a sort of prime minister to Washington and envisaged the United States as a powerful, modernized nation driven by a strong central government designed for "the accomplishment of great purposes" (Wood, 91). To achieve this lofty goal, Hamilton first turned to the national debt. On 14 January 1790, he submitted a 40,000-word report to Congress entitled Report on Public Credit, in which he proposed that the national government assume the debts of all 13 states, to be paid off by a 'sinking fund' that would retire 5% of the debt annually. This would not only strengthen the credit of the national government but also increase its legitimacy by tying the interests of wealthy and influential men to it rather than to the state governments.

Hamilton's financial plan proved controversial. Some states like Virginia and North Carolina had already paid most of their debts and saw no reason to shoulder the financial burdens of the other states. In the cabinet, Hamilton was mainly opposed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, a Virginian, who was reluctant to agree to any measure that would strengthen the national government. In the end, Hamilton and Jefferson reached a compromise; in return for Jefferson's support of the financial plan, Hamilton would support the construction of the new national capital city in the South, along the Potomac River. This agreement – known as the Compromise of 1790 – did not end the struggle between the two men. In December 1790, Hamilton proposed the establishment of a national bank, to be modeled after the Bank of England, which he hoped would foster a closer partnership between the federal government and the business classes. Jefferson and his allies again opposed this plan, believing that it would only serve the interests of wealthy Northern industrialists at the expense of the South, which was largely agrarian. Despite Jeffersonian opposition, the so-called Bank Bill was overwhelmingly approved by Congress in February 1791. By 1792, his rivalry with Jefferson had reached such a point that they could barely be in the same room.

During his time as secretary, Hamilton established the United States Mint, convinced Congress to enact a naval police force called 'revenue cutters' to crack down on smugglers, and introduced plans to stimulate industrial growth through tariffs and subsidies. In 1791, to help fund his ambitious financial program, he introduced an excise tax on distilled spirits. This proved wildly unpopular, especially along the Western frontier, where farmers relied on the distillation of whiskey to supplement their incomes and often used liquor as an informal currency. After increasingly violent protests culminated in an attack on the home of a federal tax collector, President Washington marshaled a 12,000-man federalized militia to crush the so-called Whiskey Rebellion in October 1794. Hamilton accompanied the militia as it marched through western Pennsylvania, all resistance melting before it. Although the insurrection was quelled without bloodshed, it was a demonstration of the power of the federal government, which could now command obedience even in remote regions.

Party Leader

Hamilton did not set out to establish a political party. Like most of his colleagues, he detested the idea of factionalism and was hesitant to associate himself with a party. However, his efforts at creating a modern, centralized state were bound to alienate those in the agrarian South, with the rift only widening as the Washington Administration neared its end. Hamilton and his allies formed the Federalist Party, a nationalist faction concerned with centralization, industrialization, and forging a bigger military. In foreign policy, they favored closer relations with Great Britain, which they viewed as the United States' natural ally. The Federalists were opposed by the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson and James Madison. The Democratic-Republicans accused the Federalists of being too aristocratic and believed in fostering republicanism, greater state autonomy, and agrarianism. They reviled the British and supported the concurrent French Revolution (1789-1799), which Federalists condemned as too anarchic and violent.

While in the cabinet, Hamilton schemed to align the US closer to Britain, often going behind Secretary of State Jefferson's back to confer directly with British officials. Despite the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, Hamilton persuaded Washington to keep the United States out of the French Revolutionary Wars and, in 1794, gave Chief Justice John Jay instructions for his upcoming negotiations in London. The resultant Jay Treaty, which strengthened political and commercial ties between Britain and the US, was very unpopular; Hamilton was pelted with stones while giving a speech in defense of the treaty in New York City. Yet the treaty served Hamilton's purposes, fostering closer ties with Britain while alienating the dangerous French Republic.

Later Politics & Death

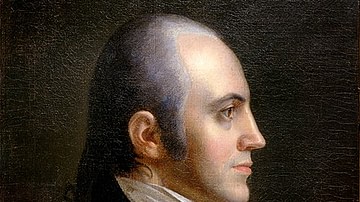

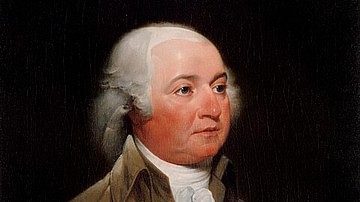

On 31 January 1795, Hamilton resigned from the cabinet. He was facing heaps of criticism for his controversial policies and wanted to step out of the public eye for a time. But his political influence remained as strong as ever. During the US presidential election of 1796, he schemed to undermine his party's nominee, John Adams; believing that Adams was not devoted enough to Hamiltonian ideals, he sought to get Thomas Pinckney elected instead. The scheme failed, and Adams was inaugurated as president in March 1797, although he retained Washington's cabinet, which was full of Hamiltonian loyalists. In 1798, a limited, undeclared naval conflict called the Quasi-War broke out between France and the US. Believing that the French would attempt an invasion of the United States, Hamilton called for a military build-up. At Washington's insistence, Hamilton was given the rank of major general and worked toward strengthening the army. He even planned an invasion of Spanish Louisiana, but hostilities were de-escalated before he could. Hamilton and his supporters denounced Adams for his timid handling of the war, creating a rift within the Federalist Party.

In the US presidential election of 1800, Hamilton worked to prevent Adams from securing a second term. This succeeded, but the two Democratic-Republican nominees, Jefferson and Aaron Burr, received an equal number of electoral votes; it was then left to the Federalist-dominated House of Representatives to break the tie and decide which candidate would become president. Most Federalists wanted to deny the presidency to Jefferson, but they were persuaded against doing so by Hamilton, who believed Burr to be the more dangerous option. Thanks to Hamilton's influence, Jefferson became president; but, by supporting the hated Jefferson, Hamilton lost much of his influence within the Federalist Party. In 1801, he moved to the Grange, a country house he had built in Manhattan. That same year, tragedy struck when his eldest son, 19-year-old Philip Hamilton, was killed in a duel while defending his father's honor; Philip's death devastated the family, especially Hamilton's daughter Angelica, who had been close with her brother and suffered a mental break shortly thereafter. Hamilton himself was said to be "completely overwhelmed with grief" (National Park Service).

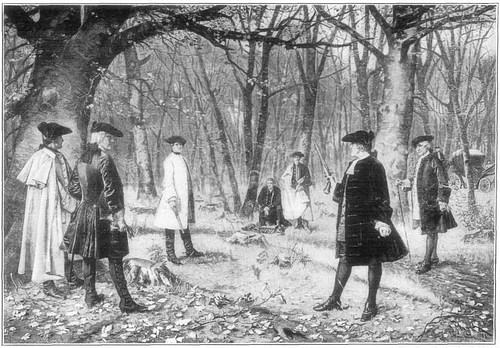

In 1804, Hamilton once again opposed the candidacy of Burr, who was this time running for governor of New York. Although many Federalists supported him, Hamilton warned them against doing so, remarking privately that Burr was "a dangerous man and one who ought not be trusted" (Chernow, 680). Burr lost the election and, when he learned of Hamilton's remarks, blamed him for the defeat. In late June 1804, Burr demanded "a general disavowal of any intention on the part of General Hamilton in his various conversations to convey impressions derogatory to the honor of M. Burr" (Wood, 384). When Hamilton refused to disavow anything, Burr challenged him to a duel. The two parties met at Weehawken, New Jersey, at 7 a.m. on 11 July 1804. To this day, scholars dispute whether Hamilton intentionally wasted his shot or if he simply overshot; in any case, he missed, while Burr's shot hit Hamilton just above his right hip. The wound proved mortal, and Hamilton died the next day, aged either 47 or 49. His death marked an end to the influence of the Federalist Party, which never again reached the heights of power it did under his leadership.