Alexander III of Scotland reigned from 1249 to 1286 CE. Succeeding his father Alexander II of Scotland (r. 1214-1249 CE) at the age of eight, the young king's early reign was blighted by rivalries between his nobles, a situation made more complex by the interference of Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE) whose daughter Alexander had married. When the king took full control of his birthright in 1259 CE, things started to improve dramatically. There was a sustained period of peace and relative prosperity for Scotland. The king even managed to grab back the Western Isles and Man from Norwegian control. The kingdom was now at its greatest extent in the medieval period so far and so Alexander's reign was looked back on as a Golden Age for Scotland. Falling to his death in an accident in 1286 CE, Alexander left no male heir, and Scotland tumbled into a protracted period of dynastic turmoil.

Early Life

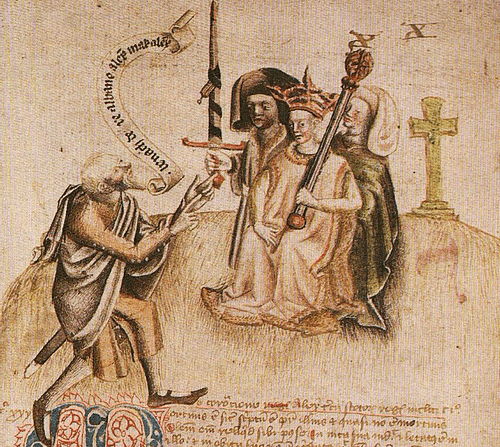

Alexander II had married Joan, the sister of Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE), but she died in 1238 CE, and the king had no heir. Alexander II married again, this time to Marie de Coucy, a French noblewoman, in May 1239 CE. The couple's only child was born on 4 September 1241 CE and named after his father. Prince Alexander was betrothed to Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England. When his father died in July 1249 CE while campaigning to wrest the Western Isles from the Norwegian Crown, Alexander became king. He was crowned on 13 July 1249 CE at Scone Abbey. The ceremony is captured in a 15th-century CE illustration in a manuscript now in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, England. The scene shows Alexander being crowned on the sacred 'Moot Hill' of Scone while a Gaelic seanchaidh (storyteller/historian) kneels before him proclaiming the long genealogy of the new king.

In 1250 CE Henry III wrote to the Pope requesting him not to accept Alexander III's coronation since he regarded the King of Scotland as his vassal because he was lord of certain estates in England. Alexander refused to bow to Henry's assertions and would only swear fealty for the English lands he held, not Scotland itself which, he said, was given to him to rule by God. The limited homage was paid when Alexander attended the wedding of Henry's son Edward in Westminster in October 1278 CE. This issue of vassal versus king was the first act in a play of tragedy that would create a long and bloody war between England and Scotland in the 14th century CE.

Government

As he was still a minor, the boy-king Alexander was served by nobles eager to promote their own position and interests. The most intense rivalry was between the Comyns and the Durwards. The two family leaders, Walter Comyn and Alan Durward, squabbled over who should have knighted the king at his coronation, an action which implied the person carrying the sword was the king's guardian and so he could serve as his regent. The Comyns eventually got the upper hand over their rivals because of the support of Henry III in 1251 CE, the English king insisting, too, that two of his own men act as the king's guardians: Sir Robert de Ros and John Balliol. However, around 1252 CE Henry got word (from Alan Durward) that de Ros was abusing his power and so the king intervened. As a consequence of this reshuffle, the balance of power shifted over to the Durwards. The Comyns did not go away, though, and returned to the fore as the decade wore on; Walter Comyn even briefly took over Edinburgh Castle in 1255 CE.

Walter Comyn again exceeded his authority in October 1257 CE when he confined the king and queen at Kinross and took charge of the royal seal. Alexander was by now 16 years of age, and he began to act more independently. The young king escaped the clutches of Walter Comywn and set up his own parliament at Stirling in April 1258 CE. In November Walter died falling from his horse and this cleared the way for a more ordered and inclusive government. However, it was not until 1259 CE that Alexander took full control of his own government. Even then, Henry III remained a constant shadow over Scottish politics throughout the first half of Alexander's reign, but at least he became preoccupied with his own problems and the rebellion in England led by Simon de Montfort.

Notwithstanding the diplomatic tussle between the English and the Scottish monarch over who was lord over what, Alexander did eventually marry Margaret (b. 1240 CE), Henry III's eldest daughter, in York on 26 December 1251 CE. Consequently, peaceful relations with England were, for the moment, perpetuated. The groom was 10 and the bride 11 years old. Unfortunately, Margaret died young on 27 February 1275 CE, and both the royal princes, Alexander (d. 1281 CE) and David (d. 1284 CE), passed away young, too. Alexander still had a daughter Margaret (b. 1261 CE) but he needed a male heir and so he married again on 1 November 1285 CE at Jedburgh, this time to Yolande of Dreux (d. 1323 CE), daughter of Jean, Count of Dreux.

Alexander III's reign, from when the king took control of his own affairs, was regarded as something of a golden period of peace and prosperity in the following centuries. Part of this is because of the wars which ravaged the country under his successors but the king did play his part by balancing the competing lords at his court and favouring neither one group nor the other. There was, too, a boom in trade, just as there was elsewhere in northern Europe. Berwick, in particular, became a thriving port, and Scottish wool, hides, and timber were traded across the continent. As silver poured into Scotland, tangible evidence of this new wealth was seen in the establishment of new monasteries, cathedrals, and castles across the land.

The Threat from Norway

Alexander's father greatly consolidated the Crown's control over Scotland, subduing rebellions in the outer regions of his kingdom. There was still one thorn in Scotland's side, though, and a much more immediate threat to the kingdom than Henry III. The Outer Hebrides or Western Isles of Scotland had been in Norwegian hands since the 11th century CE. Alexander's father had first tried to buy them back for Scotland and then attempted to take them by force. It was on this campaign that he had died of fever. Alexander III also sent a diplomatic mission to Norway to negotiate some sort of purchase deal for the disputed territory. King Haakon IV of Norway (r. 1217-1263 CE) flatly refused. It seemed a war was inevitable but when and where was the question. Alexander made himself busy strengthening his castles on both coasts, and military levies were prepared to call up troops as quickly as possible whenever and wherever they might be needed.

In August 1263 CE Haakon IV did indeed grow more ambitious, and he launched a fleet destined for Scotland. When the attackers came to northern Scotland, though, they were repulsed by Alexander's army. The Scots were greatly helped by a storm on 30 September which wrecked many of the invader's ships. This was not exactly a lucky break as Alexander had been deliberately avoiding a direct confrontation with the raiders for some time, knowing full well that as the season wore on, so the probability of storms would increase. Then the Scots, led by the nobleman Alexander Stuart, won a battle on the beaches at Largs in Ayrshire on 2 October. This Scottish victory, really a series of skirmishes, was commemorated with a large tower at Largs, which still stands at the site today.

Over the next three years, there was a long, hard military tussle and several well-timed raids against the islands that had supported the Norwegian expedition. Consequently, Haakon's successor, Magnus VI of Norway (r. 1263-1280 CE) was finally persuaded to sell the Western Isles as well as the Isle of Man. The arrangement, the Treaty of Perth, was signed by both parties in July 1266 CE. Only the islands of Orkney and Shetland remained under the control of the Norwegian Crown. Relations between Scotland and Norway were cemented on a friendly basis in September 1281 CE with the marriage of Alexander's daughter Margaret to King Eric II Magnusson of Norway (r. 1280-1299 CE). Alexander's success in expanding his kingdom was one of the most significant positives for Scotland in the 13th century CE.

Death & Successor

Tragically, on 19 March 1286 CE the king died, perhaps falling off a cliff at Kinghorn in Fife. It seems the king had simply ridden too close to the edge on a dark stormy night, and he fell to his death on the beach below or, as the contemporary sources state, he had been drinking rather too much of the Bordeaux wine he was known to be fond of and fell from his horse while riding along the beach and broke his neck. The king was buried at Dunfermline, still heirless. Queen Yolanda may have been pregnant, but when the baby was born after Alexander's death, it was either stillborn or there had been no pregnancy, to begin with. The next in line to the throne was Margaret (b. 1283 CE), aka the 'Maid of Norway', who was the infant granddaughter of the dead king. The 'Maid's' mother was Alexander III's daughter Margaret (who had died in childbirth) and her father was King Eric II.

The new English king, Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307 CE) even arranged for Margaret to marry his son Edward of Caernarfon (future Edward II of England). However, tragedy struck again when Margaret died on the sea voyage to Scotland in September 1290 CE. Consequently, Margaret was never crowned, and Alexander III was the last monarch of the House of Canmore, which had been founded by Malcolm III of Scotland (r. 1058-1093 CE). The empty throne brought an inevitable tussle for power spiced up with the involvement of Edward I of England. The winning candidate was John Balliol (r. 1292-1296 CE).