Alexander II of Scotland reigned from 1214 to 1249 CE. Succeeding his father William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214 CE), Alexander supported the northern barons in England against the unpopular King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE) and so contributed to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 CE. The Scottish king ruthlessly tightened his grip on Scotland's border regions and restored peaceful relations with his southern neighbour when he married the sister of Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE). Alexander died in 1249 CE while campaigning to wrest the Western Isles from the Norwegian Crown, and he was succeeded by his son Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286 CE).

Early Life

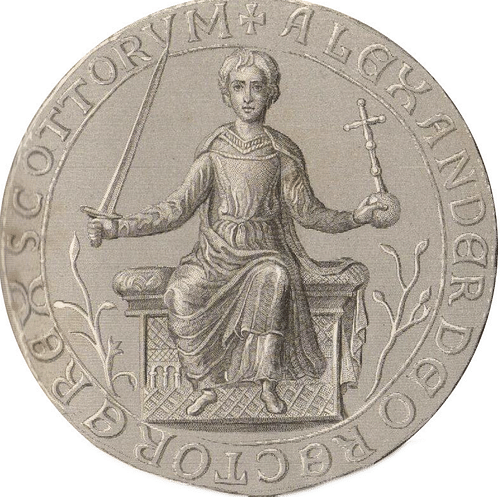

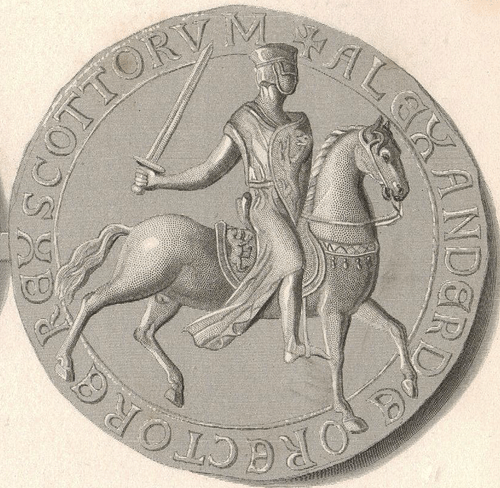

Alexander was born on 24 August 1198 CE at Haddington in East Lothian. His father was William I of Scotland and his mother was Ermengarde de Beaumont (d. 1234 CE), an illegitimate descendant of Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE). Aged just 11 and already being groomed for his future role, the young prince participated in a campaign against rebels in Ross. In addition, he was sent south to Westminster in England in 1212 CE where he was knighted by King John. William I died on 4 December 1214 CE at Stirling Castle and so he was succeeded by his son, then aged just 16, who became Alexander II of Scotland. Alexander was inaugurated as king at Scone Abbey one day later on 5 December.

Controlling Scotland

Alexander's father had done much to consolidate his control over Scotland, subduing rebellions in the regions of Galloway, Ross, and others. Some of these areas remained volatile, and Alexander was obliged to quash several minor and two sizeable rebellions in Galloway (1234-5 and 1247 CE). The young king was even more ruthless than his father had been, and when one of his bishops was murdered in the north, he rounded up 80 people who had witnessed the murder. All 80 had their hands and feet cut off. Rebel leaders were captured and beheaded, their heads then paraded in public to warn others. Those captured rebels whose lives were spared had one hand and one foot amputated. Edinburgh witnessed graphic public executions where rebels were tied to horses and their bodies ripped apart. In 1228 CE Alexander finally put an end to the line of rebellious mac Williams who had caused so much trouble in the north of Scotland, a policy of extermination that included publicly executing the last of the line, a mere child.

King John & Magna Carta

One area where Alexander's father William I had struggled to maintain Scotland's independent status was his relationship with English kings who had obliged him to sign treaties acknowledging his vassal status to Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE) and then King John of England. William had invaded northern England several times, but King John raised a large army and obliged the Scottish king to accept John as his feudal overlord in September 1209 CE. Under the Treaty of Norham, William was obliged to pay John 15,000 marks and provide two of his daughters (Margaret and Isabel) as hostages to ensure compliance with his return to vassal status.

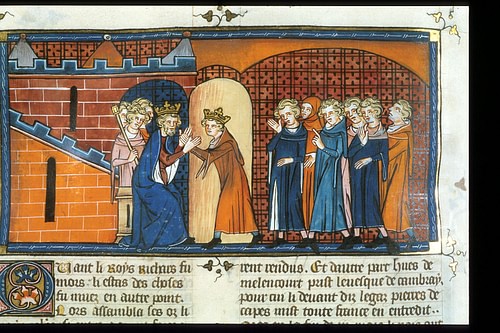

As King John's reign became ever more unpopular, Alexander now saw an opportunity not only to release Scotland from its vassal status but also to acquire lucrative land south of the border. The rebellious barons in England, tired of taxes and unsuccessful wars with France, were glad to find an ally and gave Alexander substantial estates in the north of the kingdom. King John was obliged to sign the Magna Carta in 1215 CE. The charter limited English royal power and emphasised the primacy of the law over all, including the monarchy. The Magna Carta also contained a clause that reinstated Scotland's independence from England, revoking the Treaty of Norham. King John almost immediately backed out of his promises, though, and he sent a large army not only to northern England but also to raid southern Scotland. Berwick was burnt to the ground in January 1216 CE. Alexander struck back by torching Carlisle and raiding Cumberland the following summer.

The English barons, meanwhile, now wanted to replace John with Prince Louis, son of Philip (and future Louis VIII of France, r. 1223-1226 CE). Louis invaded southeast England and took over the Tower of London and Rochester Castle. Alexander audaciously marched south to meet the French prince at Canterbury in the late summer of 1216 CE. Swearing his loyalty to Louis and probably gaining a promise that he would gain Northumberland if the Frenchman became king of England, Alexander returned to Scotland. On the way back, he had a second stab at taking Barnard Castle but failed again. With all this activity at both ends of his kingdom, King John went on the run, but he died of fever or dysentery in October 1216 CE at Newark Castle. John's successor was the much more popular Henry III of England who, with the help of such figures as Sir William Marshal, defeated Louis at Lincoln in 1217 CE. Unity was thus restored to England. Alexander, meanwhile, was excommunicated by the Pope for trying to topple a fellow monarch.

Closer Ties with England

Peaceful relations were restored between Scotland and England after Alexander paid homage to Henry III at Northampton at Christmas in 1217 CE. Ties were made stronger when Alexander married Joan (1210-1238 CE), sister of Henry, in York on 19 June 1221 CE. As part of the arrangement, Alexander also abandoned Scotland's claim to Northumberland. At the same time, Alexander's sister Margaret married Hubert de Burgh who had once served as Henry's regent and was the earl of Kent and justiciar of England.

On 25 September 1237 CE Henry III signed a treaty at York, which gave Alexander some estates in northern England, although he was forbidden to build castles there. The agreement also recognised - but without explicitly stating - that the monarchs of Scotland and England were of equal rank. This treaty, known as the Peace of York, fixed the English-Scottish border to more or less what it is today.

Unfortunately, Queen Joan died of illness on 4 March 1238 CE without the royal couple having had any children. Alexander married again, this time to Marie de Coucy, a French noblewoman, on 15 May 1239 CE. Marie was the mother of the king's heir, born on 4 September 1241 CE and named Alexander after his father. In another friendly tie with Henry III, the infant Alexander was betrothed to the English king's daughter Margaret, also then a minor.

Government

Alexander continued the policies of his predecessors in extending royal control into every corner of his kingdom. More sheriffdoms were created, feudal laws were widely applied, and royal burghs founded to promote trade, notably at Dumbarton in 1222 CE. Consequently, the 13th century CE saw a comparatively more unified Scotland but also a changing one as some of the old Gaelic families disappeared from power and Anglo-Norman ones took their place. Intermarriage between these two groups played its part in leaving many estates in the hands of nobles who had loyalties to both the Scottish and English monarch, a complication which would have repercussions in the next century when the spectre of war once more overshadowed the British Isles. For the moment, though, the main effect was to create a more homogeneous nation, no longer defined by ancestry but simply by a single name: the Scots.

Death & Successor

In 1244 CE Alexander attempted to win back control of the Western Isles which were then under Norwegian control (and had been since the 11th century CE). The Scottish king sent a diplomatic embassy to King Haakon IV of Norway (r. 1217-1263 CE) offering to pay in silver for the return of the Isles. Haakon refused and so Alexander turned to force. However, it was while on campaign that Alexander died of fever on 6 or 8 July 1249 CE on the Isle of Kerrara. The king was buried in Melrose Abbey and succeeded by his young son Alexander, who became Alexander III of Scotland. Alexander III did indeed marry Margaret, Henry III's daughter, in 1251 CE and so continued peaceful relations with England. Tragically, the king died falling off a cliff in 1286 CE, and, heirless, Alexander was the last monarch of the House of Canmore which had been founded by Malcolm III of Scotland (r. 1058-1093 CE). The next monarchs would tussle for control of Scotland, a battle won by one of the country's greatest heroes, Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329 CE), who founded his own dynasty of kings.