Alexander Severus served as the Roman emperor from 222 CE until his untimely death in 235 CE. At the urging of his mother, aunt, and grandmother, Emperor Elagabalus named his cousin Alexianus (the future Alexander Severus) as his heir in the summer of 221 CE. After realizing the possible consequences of his actions, he planned for the young Caesar's execution. Unfortunately for Elagabalus, the tide would quickly turn against him when instead of killing young Alexianus, he and his mother would meet their deaths at the hands of the Praetorian Guard. On March 11 (some say 13), 222 CE, the Roman Senate welcomed the 13-year-old as the empire's new imperial ruler.

Early Life

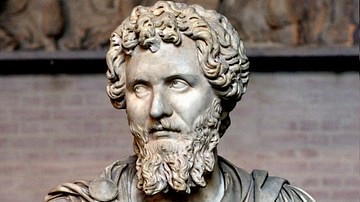

Marcus Julius Gessius Alexianus (Alexander Severus) was born in the Phoenician city of Caesarea in 208 CE (no exact date is known) to Gessius Marcianus and Julia Avita Mamaea, niece of Julia Domna - second wife of Emperor Septimius Severus. Historian Herodian wrote that Alexianus was actually named after the Macedonian king Alexander the Great. Like his cousin Elagabalus, Alexianus was also a priest of the sun god Elagabal at the Syrian town of Emesa - something his mother would keep very quiet.

In the summer of 221 CE Alexianus' mother and grandmother, Julia Maesa, as well as his aunt, Julia Soaemias, convinced Emperor Elagabalus to name his young cousin as his heir and grant him the title of Caesar telling him the appointment would give him more time to pray and dance at the altar of Elagabal. In reality, they were worried that his attempt to replace the traditional religion of Rome with that of Elagabal as well as his unorthodox lifestyle would bring about his (and their) ruin. Elagabalus' plan to assassinate his cousin failed - possible bribery of the Praetorian Guard was suspected. In order to have him accepted by the Guard, Alexianus' mother employed the same ruse that had been used for Elagabalus, namely, that Alexianus was the illegitimate son of Emperor Caracalla.

A Young Emperor

With the death of Elagabalus, Alexianus, who had assumed the name Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander, was confirmed by the Roman Senate as emperor making him the second youngest to ever sit on the throne (second only to Elagabalus). However, the young emperor would never be granted any real authority as the government would be placed firmly in the hands of his mother and grandmother - the latter would die in 224 CE. Historian Cassius Dio wrote:

He immediately proclaimed his mother Augusta and she took over the direction of affairs and gathered wise men about her son, in order that his habits might be correctly formed by them; she also chose the best men in the senate as advisors, informing them of all that had to be done.

To ease the transition and erase the memory of Elagabalus, as well as regain the trust of the citizens of Rome, the Cult of Elagabal was banished and the old gods restored. Alexander's mother wanted to portray the young emperor as a typical Roman boy with no ties to the 'Syrian god.' The large black stone that sat on Palatine Hill, symbol of the Elagabal cult, was returned to Emesa. The Elagaballum, a temple built to honor Elagabal, was renamed the Temple of Jupiter Ultor. Lastly, to appease many of the members of the old aristocracy, who were far more capable and experienced than the 'Syrian henchmen' appointed under Elagabalus, were restored to their previous positions. These changes enabled the government to return to a more conservative mentality.

Although Alexander's authority was limited, there was one individual he fought to protect (in strong opposition to his mother and the Senate): the historian and senator Cassius Dio who had been named consul for the second time. In his Roman History, Cassius Dio wrote about his relationship with Alexander:

Alexander, however, paid no heed to them, but, on the contrary, honoured me in various ways, especially by appointing me to the consul for the second time … he became afraid that they might kill me if they saw me in the insignia of my office, and so he bade me spend the period of my consulship in Italy, somewhere outside Rome.

Julia Mamaea, known as Mother of the Emperor and the Camp and the Senate and the Country, established a 16-man committee of senators to advise the young emperor which was a blatant attempt to mend the rift between the imperial throne and Senate. On a personal note, she also employed a private counselor named Domitius Ulpianus, or Ulpian, the commander of the Praetorian Guard and a former lawyer. She saw him as someone who could use his legal expertise to help with government affairs. While he assisted in helping introduce several reforms (a reduction of taxes, new aqueducts, and building projects), his old-fashioned ideas about discipline angered many within the Guard. In 224 CE this alienation between the Guard and their commander brought about three days of riots between the people of Rome and the Guard. The riots led to the death of two commanders - Julius Flavianus and Gerinius Chrestus - both killed on the orders of Ulpian. The Praetorian Guard reacted, pursuing and killing Ulpian in the imperial palace. His assassin, Marcus Aurelius Epagothus was 'rewarded' (Alexander and his mother were 'persuaded' to make the appointment) with the governorship of Egypt, but he, too, would later be assassinated.

Remembering the excesses of his predecessor and hoping to avoid controversy, in 227 CE Julia Mamaea felt the need to marry the young emperor into a respectable patrician family. She chose the family of Seius Sallustius Macrinus whose daughter Gnaea Seia Herennia Sullustia Barbia Orbiana was the intended bride. Unhappily for both Alexander and Gnaea, the emperor's mother became jealous of the young bride (she did not want another woman to have the title of Augusta) and threw her out of the palace. Her father, who some believe had received the title of Caesar, found safety for both of them in the camp of the Praetorian Guard, but this was viewed as an act of rebellion; consequently, she was exiled to northern Africa, and he was executed. Alexander would never remarry.

Unrest in the Empire

While the empire had remained in relative peace during the reign of Emperor Elagabalus, it was not the case with Alexander. Despite unrest in the army and without military experience, Alexander and, of course, his mother moved eastward to address growing tension within the provinces, arriving in Antioch in 231 CE. In 226 CE the Persian king Ardashir (Artaxerxes) had overthrown the Parthian king Artabanus and assumed complete power as the Parthian ruler, moving quickly into Mesopotamia which was an obvious threat to the eastern provinces of Rome. Despite a failed uprising in Egypt and without the full support of his army, the emperor decided to launch an assault on Ardashir. The Roman commanders chose a three-pronged offensive: one portion of the army pushed into northern Iran, a second migrated down the Euphrates to the Persian Gulf, and the last moved towards the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. Unfortunately, the extreme caution of Alexander and the lack of a coordinated attack resulted in heavy losses and what could only be called a fiasco. Although considered a 'qualified success' since the Persian forces did not advance, Alexander returned to Rome in 233 CE with morale within the army seriously damaged, and the emperor labeled a coward. In contrast, Ardashir would establish the Sassanid Dynasty that would rule Persia for over 400 years.

While still suffering from a lack of military support, Alexander and his mother decided to cross the Rhine and battle the Germans who had been attacking and plundering Roman fortifications in eastern Gaul. Again, he entered the fight without a definite plan (the only plan was to pay off the Germans) and without the full respect of the army. Combined with Julia's reductions in military expenditures as well as cuts in pay and bonuses, the army realized the inadequacies of Alexander and sought a new emperor, and the man they chose was Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus or Maximinus Thrax, a barbarian from Thrace. He would become the first of what historians call the 'Barracks Emperors.' The historian Herodian said:

…the soldiers bitterly resented this ridiculous waste of time. In their opinion Alexander showed no honorable intention to pursue the war and preferred chariot-racing and a life of ease, when he should have marched out to punish the Germans for their insolence.

An Untimely Death

In the spring of 235 CE, Maximinus was awarded the purple (a symbol of imperial authority) by his troops. They quickly moved towards Alexander's camp.

When Alexander was told what had happened, he was panic-stricken and utterly dumbfounded by the extraordinary news. He came rushing out of the imperial tent like a man possessed, weeping and trembling and raving against Maximinus for being unfaithful and ungrateful …. (Herodian).

Alexander and his mother were murdered at Vicius Britannicus, and according to some sources, their bodies were returned to Rome. The Historia Augusta stated, “… it is generally agreed that those who killed him were soldiers, for they hurled many insults [at] him, speaking of him as a child and of his mother as greedy and covetous.” The authors added, “Alexander did everything in accordance with his mother's advice, and she was killed with him.”

The new emperor would, though, never set foot in Rome. Unfortunately, the imperial throne could not be easily awarded and following the death of Alexander there occurred what is called “The Year of the Six Emperors.” It would be some time before Gordian III would sit, without opposition, upon the imperial throne.