Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) was a Franco-British impressionist painter. Known for his landscapes, which often present nature in a subdued light, he participated in the impressionist exhibitions in Paris in the 1870s but struggled to make a living from his art. Only after his death did the critical and public attitude change, sending the prices of Sisley's canvases skyrocketing.

Early Life

Alfred Sisley was born in Paris on 30 October 1839. Both of his parents were English, with his father William having that same year established his successful luxury goods import-export business in the French capital. Despite living all his life in France, Alfred kept his British citizenship. He was a quiet and retiring young man, and his character did not change as he got older. As one art critic once wrote: "Sisley lived the life of a selfless, reflective landscape painter, with a deep love of nature, who distanced himself from social life" (Bouruet Aubertot, 328).

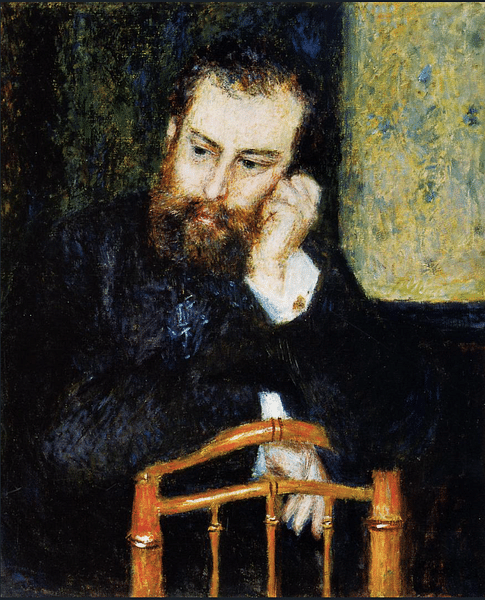

Sisley's father sent his son to London in 1857 in the hope he would acquire the necessary skills to assist in the family business, but Alfred was not interested in such matters. For Alfred, his future lay in the world of art. As a consequence, Sisley returned to Paris in 1860, and, a year or so later, he began to study fine art in the studio of Charles Gleyre (1808-1874), where he met fellow students Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870). Sisley's art education was paid for by his father, and his allowance meant he could live and dress well. The young artists went on painting trips together to such picturesque villages as Chailly and Marlotte, as well as the forest of Fontainebleau, all just outside Paris. The group also spent time painting outdoors in the brisk air of Normandy.

In the late 1860s, Sisley lived with his long-term partner Marie-Eugénie Lescouezec and their son Pierre (b. 1867) in Montmartre. Alfred and Marie-Eugénie would not get married until 1897. Marie-Eugénie was older than Albert by some years and a mere part-time model and florist, which probably cost the artist his regular allowance from his disapproving father (who, in any case, suffered badly from the economic slump and general turmoil of the early 1870s).

Argenteuil, Louveciennes, & Marly

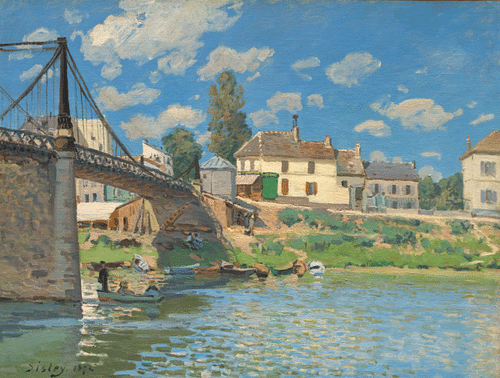

Sisley worked at Argenteuil in 1871-2, visiting Monet, who lived there, and he worked alongside Renoir, who also dropped in for painting spells outdoors, capturing bourgeoise Parisians enjoying their weekends, boating and frolicking on the Seine. Together, they developed the style that would become known as impressionism (see below).

Sisley stayed with his family in Louveciennes in the chaotic and violent aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. The war had a serious effect on the Sisley family's finances, and the artist's studio was ransacked by Prussian soldiers during the conflict, destroying much of his early impressionist work. In 1874, he took a trip to England, visiting Hampton Court. This trip was funded by the famous baritone singer and art collector Jean-Baptiste Faure on the condition that Sisley gave him six new paintings. The artist produced 16 canvases of river scenes, notably boatsmen rowing and the annual regatta. Faure acquired his six paintings for his impressionist collection, which, in the end, contained nearly 60 works by Sisley.

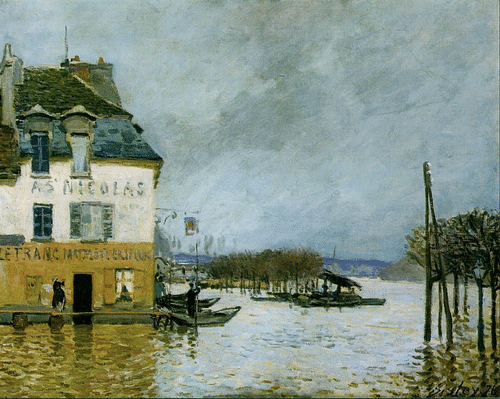

In 1875, Sisley moved to Marly-le-Roi, the village next to Louveciennes which was once the summer retreat of King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). The next spring, Sisley produced a series of six canvases capturing the catastrophic flooding of the Seine at Port-Marly. He shows moody skies pressing down upon the floodwaters while people walk across planks and skiffs act as temporary ferries. Still struggling to make money, Sisley was obliged to move to nearby Sèvres in 1879 where the rents were cheaper.

Impressionism

Impressionism involved the attempt to capture in paint the temporary effects of light and colour, using quick and bold brushstrokes while working outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist artists used a much more colourful palette than had been previously used in fine art and they took nature and everyday life as their main subject rather than the more traditional mythological and religious scenes. For example, in the oil on canvas The Regatta at Molesey (1874), Sisley captures the impression of flags caught in a breeze. The artist wrote, "These effects of light which have an almost material expression in nature must be rendered in material fashion on the canvas" (Howard, 87).

This new approach was contrary to the ultra-conservative art establishment and made it very difficult for impressionists like Sisley to have their work shown in the one place that could make one's reputation and bring lucrative commissions: the Paris Salon. Sisley had a Salon submission accepted in 1865, but his work was rejected for the Salon of 1867. The next year his work was chosen for public view by the fickle Salon jurists. This in-out relationship with the Salon would continue for some years. Eventually, Sisley and the other impressionists realised the best way forward was to put on their own shows where they could decide what paintings to include and how to display them to the best effect. Meeting and discussing art regularly in the capital's cafés, the impressionists formed a cooperative and organised the Paris Impressionist Exhibitions, 1874-86.

Sisley participated in the First Impressionist Exhibition of April 1874, exhibiting five landscapes. The show did not even cover its costs, although Sisley, with 1,000 francs from sales, made more than any other artist from it. The next year, Sisley had 20 paintings in the disastrous auction the impressionists organised in the Hôtel Drouot in Paris. The critics and public were relentless, as the art dealer and organiser Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922) later described:

The insults they hurled at us…The public howled, treated us as imbeciles, as people with no sense of decency. Works were sold for as little as 50 francs…and that was only because of their frames…Afterward it seemed that I was about to be taken to a lunatic assylum…

(Howard, 80)

Clearly, it was going to take some time for people to warm to this new art style, but the impressionists were undeterred.

Alfred Sisley: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

Sisley participated in the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876 and the third in 1877 but pulled out of the next three in 1879, 1880, and 1881 after disagreeing with the inclusion of several mediocre artists (Renoir and Monet were of the same opinion and were also absent). Sisley also wanted to continue to submit to the Salon, which some members of the impressionist group, notably Edgar Degas (1834-1917), insisted precluded them from participating in the independent shows. As it turned out, Sisley's submissions to the Salon were not accepted, and his financial situation sank so low he was forced to ask for a bale-out from friends.

Sisley returned for the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition in 1882 after the number of artists involved was dramatically reduced to what we might today call the 'real' impressionists (Monet and Renoir also returned). The show was much more homogeneous as a consequence, and the critics were beginning to come around to this new art style. Still, sales were not great, and Sisley decided to abstain from the eighth and final show in 1886.

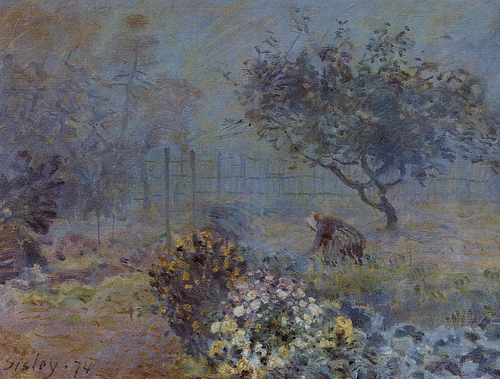

The Sisley Style

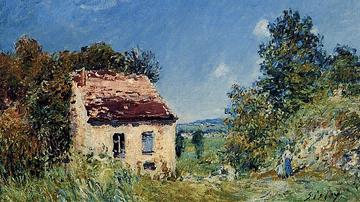

Sisley was principally a landscape painter, and his work, at least in the first part of his career, was quite traditional and realistic. He was most influenced by – or at least his work most resembles – the landscapes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) in that he produced canvases of harmonious composition with subtle tonal variations. As he employed more and more impressionist techniques, Sisley's work became less conservative, although he remains one of the less experimental painters of the impressionist group, certainly in the latter part of his career. Sisley's palette is comparatively subdued as he liked to paint scenes in early morning light or at the end of the day. His brushstrokes are often lively, but they are almost always controlled. He liked to paint road scenes in small towns, typically devoid of human activity but with an occasional figure added for an effect, such as a dark silhouette walking down a snow-covered lane. Bridges, snow scenes, and avenues of trees were his favourite subjects.

Growing Reputation

In the 1880s, Sisley's financial situation finally improved as he benefitted from solo shows organised by the art collector Georges Charpentier (1846-1905) and Durand-Ruel who now gave him a regular income for his paintings. Sisley also established a good working relationship with Durand-Ruel's rival dealer Georges Petit (1856-1920), and in 1882, Sisley participated in the Universal Exposition in Paris. In 1883, Sisley was represented in an impressionist exhibition in Boston, in 1885 in Brussels, and in 1886 in New York. The reaction to these international shows, even if it did not necessarily materialise into sales, was often more favourable than it had been in France.

Around 1882 and in search of even cheaper rents, Sisley moved to Moret-sur-Loing where he spent the rest of his life in relative isolation from his fellow artists with the exception of Monet. Sisley painted a series of 14 or more views of the old church at Moret in various light conditions between 1893 and 1894. Indeed, it was the light effects that the artist was really interested in capturing, not the church itself.

Death & Legacy

Sisley did not enjoy good health in his later years, and he suffered from acute rheumatism and several episodes of depression. Both terminally ill, Sisley finally married his partner in 1897 during a stay in South Wales. The artist died of throat cancer in his home in Moret on 29 January 1899. Almost immediately after Sisley's death, the prices of his paintings began to rise. In 1900, Sisley's work was selected to represent French art in the Universal Exhibition. Perhaps recognition and money had not really been of that much concern to Sisley, who essentially lived only for his art. As he himself once said, "To give life to the work of art is certainly one of the most necessary tasks of the true artist" (Howard, 86). At least he had been recognized by his peers. Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) lamented after Sisley's death: "He is a great and beautiful artist, in my opinion he is a master equal to the greatest" (Howard, 87).