Ali ibn Abi Talib, or simply Ali, (l. 601-661 CE) was among the first Muslims, a cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE), and later reigned as the fourth Caliph of Islam from 656 CE to 661 CE, when he was murdered. Much of his tenure was spent bringing the empire to order during the first civil war of the Islamic Empire or the First Fitna (656-661 CE). A faction of the Islamic community, known as the Shia Muslims, consider him as the sole legitimate heir of Muhammad's temporal position, and the first in a long series of their spiritual leaders or imams. Sunni Muslims, another faction within the community, hold him with special reverence but also consider his three predecessors, Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE), Umar (r. 634-644 CE) and Uthman (r. 644-656 CE) as equally rightful leaders of the early community and collectively term the four as the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE).

Early Life & Conversion

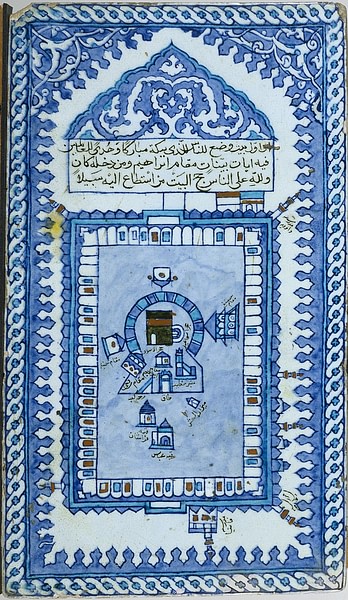

Ali was born in Mecca, by some accounts inside the holy sanctuary of Ka'aba, in 601 CE. He was the son of the leader of the Hashim clan, Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib (l. c. 535-619 CE), the uncle of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. His father had raised the Prophet, who had been orphaned at an early age as if he were his son and a similar relation developed between the Prophet and Ali. From an early age, Ali formed a strong bond with Muhammad, who took him in his household. In 610 CE, when Muhammad declared his prophethood, Ali was among the first people to accept the new faith (the identity of the first male convert is a matter of debate but Ali is among the candidates), and he remained loyal to him even in the direst of situations.

Ali's father died in 619 CE, leaving only Muhammad as a patriarchal figure in his life, who had been widowed the same year, known as the "year of sorrow" in the Islamic tradition. Met with violent oppression at the hands of the Meccans, the Muslims migrated to Medina in 622 CE (known as the Hegira); the Prophet himself departed later on with a close friend of his, Abu Bakr. On the eve of Muhammad's departure from Mecca, to seek asylum in Medina (where he was destined to become a king), Ali stayed behind to return people the possessions they had entrusted upon the Prophet for safekeeping.

Ali became deeply entwined in the Islamic movement in Medina, where he served as a deputy and envoy for the Prophet and became one of his most trusted subordinates. Ali was much celebrated for his proverbial wisdom, so much as to be famous by the name of the Bab ul-Ilm (gate to knowledge). Learning from the Prophet, he became one of the focal persons for addressing theological queries.

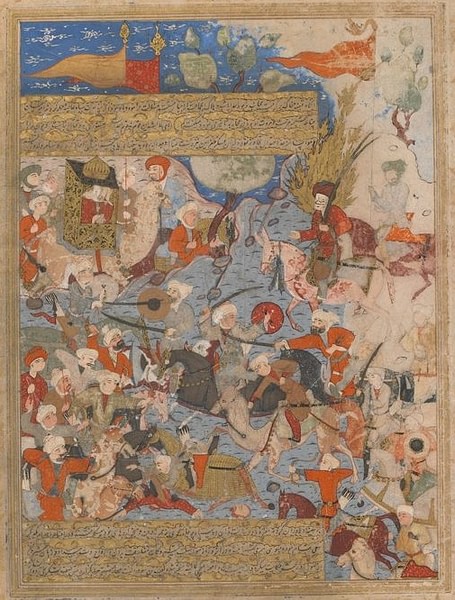

His feats in battle, however, are responsible for bringing the most fame to him; his valiance and undeterred courage earned him the nickname of Asad Allah – the Lion of God. Ali participated in almost every major battle of early Islamic history as the standard-bearer of his army. On the eve of the Battle of Badr (624 CE), the first battle against the Meccans, he is said to have slain multiple opponents single-handedly. A year later at the Battle of Uhud (625 CE), where the Muslims suffered a stinging defeat, Ali stood by the side of the Prophet who was hurt and vulnerable, risking his own life while acting as his mentor's sentinel. These are but a handful of narratives that appraise his courage, devotion to Islam, and skill in battle.

Rise to Power

Prophet Muhammad passed away in the year 632 CE, after which a close companion of his, Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) took charge of the community as the first Caliph of Islam. But to some, the rightful heir to Muhammad's empire was Ali. These people came to be known as Shia Muslims, and they based their argument on the fact that before his death the Prophet had announced that whoever held him as his mawla, would feel likewise about Ali (this is known as the Event of Ghadir Khumm). The word mawla, however, is a polysemous word, with meanings ranging from friend to leader – this inherent ambiguity led to another group, called the Sunni Muslims, asserting that the Prophet had not explicitly announced an heir, and hence they declared their support for Abu Bakr.

After him, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644-656 CE), the first Meccan patrician to accept the new faith, became the next leader of the ummah (community). Uthman ruled for well over a decade but relied heavily upon his kinsmen from the Umayya clan (later Umayyad Dynasty), and by the end, he faced an open revolt and was murdered by rebel soldiers in 656 CE. It was then, over two decades after the demise of the patriarch of his household, that Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656-661 CE) was raised to the throne, as the fourth Caliph of Islam.

First Fitna (656-661 CE) Erupts

Upon assuming the office, Caliph Ali sought to restore order, he dismissed several provincial governors, most of whom were corrupt and had been set in place by Uthman (who had lost control over them later). While some folded before the new Caliph's might, others defied him. Uthman's murder had created deep fissures in the community, and his kinsmen from the Umayya clan, most notably the governor of Syria – Muawiya (l. 602-680 CE), demanded justice. They refused to settle for anything less than an exemplary punishment for his assailants. The bloodstained shirt of the deceased Caliph and the cut fingers of his wife (who had bravely attempted to save him) were displayed publically in the mosque of Damascus to gain support for the fallen leader's cause.

Battles of the Camel & Siffin

The opposing parties met at Basra in Iraq, sensible leaders from both sides pushed for negotiations which soon turned futile, and open war broke out. Ali did not wish to have Muslim blood on his hands, just like his predecessor Uthman who had refused to crush the rebels against him; he ordered his men to capture Aisha, who was seated atop a camel. The men did as such, and seeing their leader captured, Aisha's army ceased fighting; she was sent back to Medina with every mark of honor. The Battle of the Camel (656 CE), as it was later fashioned, became the first time in Islamic history when Muslims took to arms against fellow Muslims.

A radical group, who had vehemently supported peaceful resolution initially, and some of whom were involved in Uthman's murder, declared that “arbitration belongs to God alone” (a convenient way to suggest that they were hostile to both parties), and deserted Ali. This group, later branded as the Kharijites ('those who go out'), declared rebellion against Ali. Muawiya continued to defy Ali's authority and gained complete support of Syria, Levant, and Egypt – where he reinstated Amr, his ally, as the governor.

Domestic Affairs & Challenges

Kufa, an Iraqi garrison city built during the reign of Caliph Umar, was the hub of Ali's support, prompting him to shift his capital to that city in January 657 CE, shortly after his victory near Basra. This move was highly controversial, as Medina had been the Prophet's seat of power and his final resting place. The shift was done mostly for political reasons:

- to seek support

- to rule over the empire from a centralized position

- to safeguard Medina from the havocs of the civil strife that had ensued.

Ali sought to reestablish central control over provinces and to distribute state revenue equally among people. His strict anti-corruption stance, although a valuable trait, became a hurdle for him as this diminished his support. Governors of key provinces, placed by Uthman, defied caliphal authority and were hoarding money for their personal use. Ali refused to accept this, which made those who had hitherto enjoyed immunity under Uthman's weak leadership his enemies.

Death & Aftermath

The Kharijite zealots had turned into a menace and needed to be dealt with. Ali unleashed his military might on these traitors and dealt upon them a pulverizing defeat in 659 CE (the Battle of Nahrawn). With their military prowess crushed, the Kharijites resorted to underground movements to achieve their goals. They struck down the Caliph with a poisoned sword in 661 CE, while he was offering prayer in congregation. Kharijite assassins had targeted Muawiya and Amr as well, but both escaped death; the latter was never attacked while the former survived with only a minor injury.

On the morrow of the Caliph's death, Muawiya stood as the strongest competitor for the Caliphate, and it was then that he unveiled his plans to take the throne. Ali's supporters were quick to raise Hasan (l. 624-670 CE), his eldest son, to the caliphal seat, but Muawiya forced him to abdicate, in return for a high pension. Although Muawiya agreed not to name his successor, this oath was to be broken, and the foundation of the institutional monarchy in the Islamic Empire embodied by the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE) was laid down by Muawiya. Umayyads had zero tolerance for insurrections; what bribery and cajolery failed to do would easily be coerced via the use of force.

Posthumous Fame & Legacy

During his lifetime, Ali was simply thought of as a leader, not revered and venerated as he is in the present. As Shiism evolved from a political faction to a religious group, it started diverging from the mainstream Sunnis. In the words of historian John Joseph Saunders: “…indeed it has been claimed that the Shia were initially more Sunni than the Sunnis themselves are today” (127-128). Subsequent events, such as the martyrdom of Hussayn (l. 626-680 CE), Ali's second eldest son in 680 CE at the hands of Umayyad forces at the Battle of Karbala, elevated the household of Ali into a higher spiritual, almost divine position within Shia Islam and a distinctly respectful one within Sunni Islam.

Ali ibn Abi Talib, was, without doubt, a man of honor. The failures of his reign are accredited to the severe opposition he had been met with; had he ruled over a more peaceful time, his talents would have blossomed excellently. To both Sunnis and Shias, Ali remains a hero, he is regarded highly by both and venerated specifically by the latter. Despite the brevity of his tenure, Ali left a lasting legacy – an inspiration for all future rulers who wished to act upon solid principles of justice, and as an epitome of Arabic chivalry.