Amarna is the modern Arabic name for the site of the ancient Egyptian city of Akhetaten, capital of the country under the reign of Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE). The site is officially known as Tell el-Amarna, so-named for the Beni Amran tribe who were living in the area when it was discovered.

A 'tell' in archaeology is a mound created by the remains of successive human habitation of an area over a given number of years. As each new generation builds on the ruins of the previous one, their buildings rise in elevation to create an artificial hill. Amarna differs from the usual 'tell' in that it did not fall to a foreign power or earthquake and was never built over in antiquity; it was instead destroyed by order of the pharaoh Horemheb (c. 1320-1292 BCE) who sought to erase Akhenaten's name and accomplishments from history; afterwards its ruins lay in the plain by the Nile River for centuries and gradually was built on by others who lived nearby.

When he came to power, Akhenaten was a powerful king entrusted – as all kings were – with the maintenance of ma'at (harmony and balance) in the land. Ma'at was the central value of the culture which allowed all aspects of life to function harmoniously as they should. It came into being at the beginning of creation and so, naturally, a king's observance and maintenance of ma'at relied heavily on the proper veneration of the gods through traditional rites and rituals.

Although Akhenaten initially kept to this practice, in around the fifth year of his reign (c. 1348 BCE) he abolished the ancient Egyptian religion, closed the temples, and imposed his own monotheistic vision on the people. This innovation, though hailed by monotheists for the last hundred years, crippled the Egyptian economy (which relied heavily on the temples), distracted the king from foreign affairs, stagnated the military, and resulted in Egypt's significant loss of status among neighboring lands.

It is for these reasons that Akhenaten's son and successor, Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327 BCE), returned Egypt to traditional religious practices and rejected the monotheism of his father. He did not live long enough to complete the restoration of Egypt, however, and so this was accomplished by Horemheb. This era in Egypt's history is known as the Amarna Period and is usually dated from Akhenaten's reforms to Horemheb's reign: c. 1348 - c. 1320 BCE.

The City of the God

The god Akhenaten chose to replace all the others was not his own creation. Aten was a minor solar deity who personified the light of the sun. Egyptologist David P. Silverman points out how all Akhenaten did was elevate this god to the level of a supreme being and attribute to him the qualities once associated with Amun but without any of that god's personal characteristics. Silverman writes:

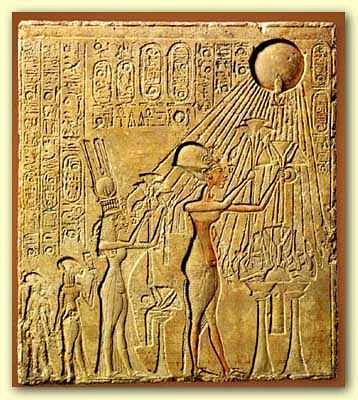

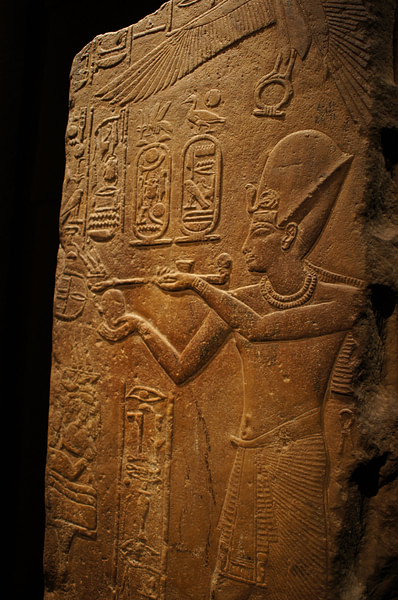

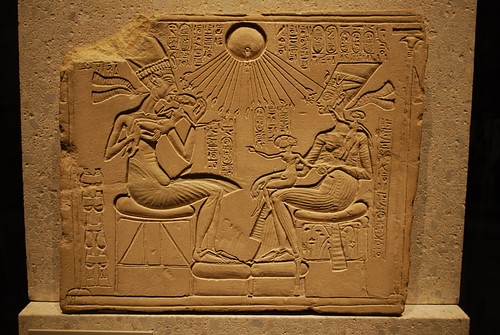

Unlike traditional deities, this god could not be depicted: the symbol of the sun disc with rays, dominating Amarna art, is nothing more than a large-scale version of the hieroglyph for 'light'. (128)

Akhenaten's one true god was light, the light of the sun, which sustained all life. Unlike the other gods, Aten was above human concerns and possessed no human weaknesses. As Akhenaten expresses in his Great Hymn to the Aten, his god could not be jealous or depressed or angry or act on impulse; he simply existed and, by that existence, caused all else to exist. A god this powerful and awe-inspiring could not be worshiped at any other god's repurposed temple nor even in any city which had known the worship of other deities; he required a new city built solely for his honor and adoration.

This city was Akhetaten, built midway between the traditional capitals of Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. Boundary steles were erected at intervals around its perimeter which told the story of its founding. On one, Akhenaten records the nature of the site he chose:

Behold, it is Pharaoh, who found it – not being the property of a god, not being the property of a goddess, not being the property of a male ruler, not being the property of a female ruler, and not being the property of any people. (Snape, 155)

Other stelae and inscriptions make clear that the foundation of the city was entirely Akhenaten's initiative as an individual, not as a king of Egypt. A pharaoh of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) would issue a commission for the building of a city or temple or erection of obelisks or monuments in his royal name and for the glory of his particular god, but these projects were to benefit the nation collectively, not just the king. Akhenaten's city was built for the sole purpose of providing him with an elaborate sacred precinct for his god.

Design & Layout

Akhetaten was laid out over six miles on the east bank of the Nile between the shore and the cliffs above Assiut. Some boundary stelae were carved directly into the cliffs with others free-standing on the far side of the city. The four main districts were the North City, Central City, Southern Suburbs, and Outskirts; none of these names were used to designate the locales in antiquity.

The North City was constructed around the Northern Palace where guests were received and Aten was worshiped. The royal family lived in apartments to the rear of the palace and the most opulent rooms, painted with outdoor scenes depicting the fertility of the Delta region, were dedicated to Aten who was thought to inhabit them. The palace had no roof – a common feature of the buildings at Akhetaten – as a gesture of welcome to Aten.

The Central City was designed around the Great Temple of Aten and the Small Temple of Aten. This was the bureaucratic center of the city where the administrators worked and lived. The Southern Suburbs was the residential district for the wealthy elite and featured large estates and monuments. The Outskirts were inhabited by the peasant farmers who worked the fields and on the tombs of the necropolis.

Akhenaten himself designed the city for his god, as his boundary stelae make clear, and refused suggestions or advice from anyone else, even his wife Nefertiti (c. 1370 - c. 1336 BCE). Precisely what kind of suggestions she may have made is unknown, but the fact that Akhenaten makes a point of stating that he did not listen to her advice would seem to indicate they were significant. Egyptologist Steven Snape comments:

It is obvious that the 'prospectus' for the new city carved on the boundary stelae is deeply concerned with describing the provision that will be made for the king, his immediate family, the god Aten, and those religious officials who were to be involved with the cult of the Aten. It is equally obvious that it utterly ignores the needs of the vast majority of the population of Amarna, people who would have been moved (possibly unwillingly) from their homes to inhabit the new city. (158)

Once Akhenaten moved his capital to Akhetaten, he focused his attention on the adoration of Aten and increasingly ignored affairs of state as well as the condition of the country outside of the city which was slipping into decline.

Akhenaten's Reign & Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters are cuneiform tablets discovered at Akhetaten in 1887 CE by a local woman who was digging for fertilizer. They are the correspondence found between the kings of Egypt and those of foreign nations as well as official documents from the period. The majority of these letters demonstrate that Akhenaten was an able administrator when a situation interested him personally but also that as his reign progressed he cared less and less for the responsibilities of a monarch.

In one letter, he strongly rebukes the foreign ruler Abdiashirta for his actions against another, Ribaddi (who was killed), and for his friendship with the Hittites who were then Egypt's enemy. This no doubt had more to do with his desire to keep friendly the buffer states between Egypt and the Land of the Hatti - Canaan and Syria, for example, which were under Abdiashirta's influence - than any sense of justice for the death of Ribaddi and the taking of Byblos.

There is no doubt that his attention to this problem served the interests of the state but, as other similar issues were ignored, it seems that he only chose to address issues which affected him personally. Akhenaten had Abdiashirta brought to Egypt and imprisoned for a year until Hittite advances in the north compelled his release but there seems a marked difference between his letters dealing with this situation and other king's correspondence on similar matters.

While there are examples like this one of Akhenaten looking after state affairs, there are more which provide evidence of his disregard for anything other than his religious reforms and life in the palace. It should be noted, however, that this is a point often – and hotly - debated among scholars in the modern day, as is the whole of the so-called Amarna Period of Akhenaten's rule. Regarding this, Dr. Zahi Hawass writes:

More has been written on this period in Egyptian history than any other and scholars have been known to come to blows, or at least to major episodes of impoliteness, over their conflicting opinions. (35)

The preponderance of the evidence, both from the Amarna letters and from Tutankhamun's later decree, as well as archaeological indications, strongly suggests that Akhenaten was a very poor ruler as far as his subjects and vassal states were concerned and his reign, in the words of Hawass, was "an inward-focused regime that had lost interest in its foreign policy" (45).

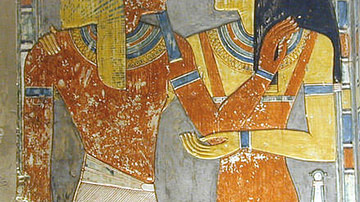

Akhenaten saw himself and his wife not just as servants of the gods but the incarnation of the light of Aten. The art of the period depicts the royal family as strangely elongated and narrow and, while this has been interpreted by some as "realism" it is far more likely symbolism. To Akhenaten, the god Aten was unlike any other – invisible, all-powerful, omniscient, and transformative – and the art from the period would seem to reflect this belief in the curiously tall and thin figures depicted: they have been transformed by the touch of Aten.

Destruction of the City

The city flourished until Akhenaten's death; afterwards, Tutankhamun moved the capital back to Memphis and then to Thebes. Tutankhamun initiated the measures to reverse his father's policies and return Egypt to the former beliefs and practices which had maintained the culture and helped it develop for almost 2,000 years. Temples were reopened, and the businesses which depended upon them were renewed.

Tutankhamun died before he could finish these reforms, and they were carried on by his successor, the former vizier Ay, and then by Horemheb. Horemheb had been a general under Akhenaten and served him faithfully but disagreed vehemently with his religious reforms. When Horemheb came to the throne, Akhetaten was still standing (as evidenced by a shrine to him built there at this time) but it would not remain intact for long. He ordered the city razed and its remains dumped as fill for his own projects.

Horemheb was so dedicated to erasing the name and accomplishments of Akhenaten that he does not appear in any of Egypt's later historical records. Where he had to be cited it is only as "the heretic of Akhetaten" but never named and no reference made to his position as pharaoh.

Discovery & Preservation

The ruins of the city were first mapped and drawn in the 18th century CE by the French priest Claude Sicard. Other Europeans visited the site afterwards, and interest in the area was piqued after the discovery of the Amarna Letters. It was further explored and mapped in the late 19th century CE by Napoleon's corps of engineers during his Egyptian campaign, and this work attracted the attention of other archaeologists once the Rosetta Stone was deciphered and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics could be read in c. 1824 CE. Akhenaten's name was therefore known but not his significance. It was not until archeologists in the early 20th century CE found the ruins Horemheb had dumped as fill that the story of Akhenaten was finally put together.

In the present day, the site is a wide, barren, expanse of ruined foundations which is being preserved and excavated by The Amarna Project. Unlike the ruins of Thebes or the village of Deir el-Medina, there is little left of Akhetaten for a visitor to admire. Egyptologist Steven Snape comments, "apart from the modest reconstructions of parts of the city by modern archaeologists, there is virtually nothing to be seen of the city of Amarna" (154). This is not unusual as the cities of Memphis and Per-Ramesses, both also capitals of ancient Egypt – as well as many others – are largely vacant lots today with far fewer monuments than those extant at Amarna.

What makes Amarna a special case in this regard is that the city was not leveled by time nor by an invading army but by the successor of the king who built it. At no other time in Egypt's ancient history was a city destroyed by a king's successor to blot out his name. To remove one's name from a temple or monument or tomb was to condemn them for eternity, but in this instance, only the removal of an entire city would satisfy Horemheb's sense of justice.

The Egyptians believed one had to be remembered by the living in order to continue one's eternal journey in the afterlife. In Akhenaten's case, it was not just a tomb or temple which was defaced but the totality of his life and reign. All of his monuments, in every city across Egypt, were torn down and every inscription bearing his name or that of his god was edited with chisels. Akhenaten's heresy was considered so serious, and the damage done to the country so severe, that he was thought to have earned the worst punishment that could be meted out in ancient Egypt: non-existence.