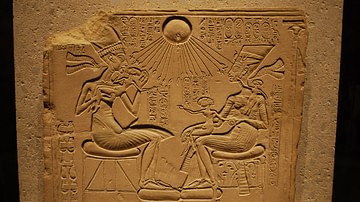

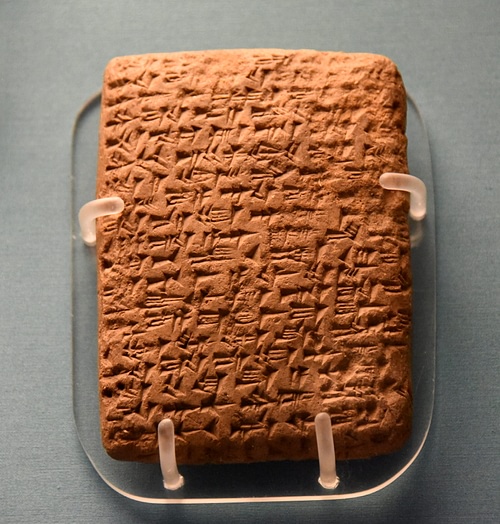

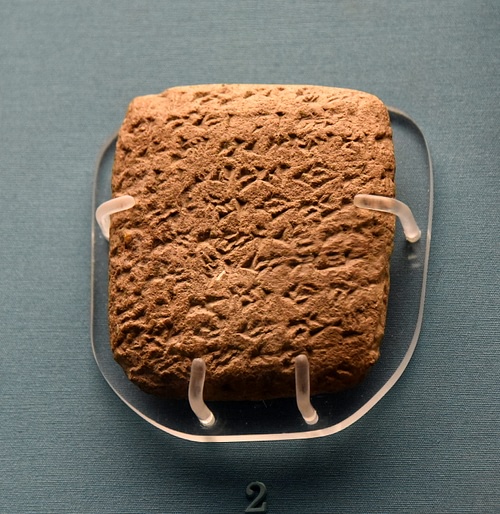

The Amarna Letters are a body of 14th-century BCE correspondence exchanged between the rulers of the Ancient Near East and Egypt. They are perhaps the earliest examples of international diplomacy while their most common subjects are negotiations of diplomatic marriage, friendship statements, and exchanged materials. The name “Amarna Letters” derives from the place where the tablets were found: the ancient city of Akhetaten (built by order of the Pharaoh Akhenaten), but nowadays known as Tell el-Amarna, in Egypt.

The first letters were found in 1887 CE and date back to the 14th century BCE. They are the first international diplomatic system known to us, i.e. they contain rules, conventions, and institutions responsible for communication and negotiation. Although in the early 3rd millennium BCE there was already another form of relationship, this was merely straightforward written communication between Mesopotamia and Syria. With time, this form added some rules, based on necessity and developed the beginning of diplomatic mechanisms, which would culminate in the Amarna system. Thus, diplomacy was created to be used as a tool in the process of creating an empire.

Even though the simpler form of communication between states already existed, it was the Amarna diplomatic system that expanded relationships throughout the Near East, establishing terms of equality among the Great Powers (Babylon, Hatti, Egypt, Mitanni, Assyria) for the first time. The Amarna Letters show us that great kings from the ancient world had both responsibilities and privileges which were held with power and respect. Therefore, the Amarna system brought a notion of stability and peace, although not always real, for more than two centuries.

The tablets cover the reigns of the rulers Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and possibly Smenkhkare or Tutankhamun, of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. Nonetheless, the system continued to be used for approximately a hundred years after the end of the Amarna Period.

The researchers R. Cohen and R. Westbrook tell us the importance of studying the Amarna Letters. They say that people nowadays should pay more attention to them, as these tablets are the first known diplomatic system. By seeing the mechanisms used in the past, we can learn about different kinds of relationships and how they changed and were modified through time. This means that we can learn more about the contacts between such distant civilizations, acknowledging that isolation was not part of ancient life. By realizing the sophistication of international relations in this period, our way to perceive the distant past can drastically improve.

Structure of the Letters

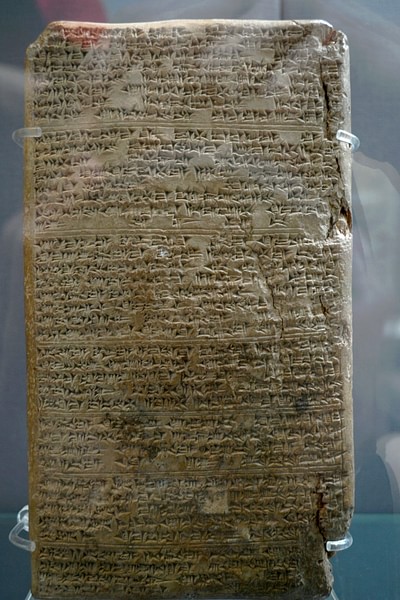

There are 382 known tablets, ordered chronologically and geographically with the acronym “EA”, by J. A. Kunudtzon, in 1907 CE. However, when Knudtzon organized the tablets, in the “Die El-Amarna-Tafeln”, only 358 of them were known, so the other 24 tablets were analyzed in 1970 CE by Anson F. Rainey, with the exception of EA 80-82.

Some of these tablets (32) are not letters, but probably training material for scribes. The letters themselves were organized by Jean Nougayrol in two groups: lettre d'envoi (indicating what is being sent) and lettre d'injonction (making requests). The major part of this correspondence is a combination of these two types, i.e. the letters name gifts sent and ask for something in return.

Most of the letters were received by the Egyptians, only a few of them were written by the Pharaoh. We do not know why these letters were together, but maybe they were never sent or were retained copies. Furthermore, in addition to the letters for training purposes, there are two other subdivisions: the international ones (which the Egyptian rulers exchanged between the great powers of the Near East and the independent kingdoms); and the administrative ones (exchanged between the Syrian-Palestine region, mostly Egyptian vassals).

Training Purposes

Due to the current stage of research, we do not know much about these 32 training tablets. They have various themes such as myths and epics (EA 356-59, and probably EA340 and EA 375), syllabary (EA348, 350, 379), lexical texts (EA 351-54, 373), lists of gods (EA374), a tale of Hurrian origin (EA341), a list of Egyptian words written in cuneiform with Babylonian equivalences (EA368), and one tablet is perhaps an amulet (EA355). According to William Moran, the rest of them (EA 342-47, 349, 260-61, 372, 376-77, 380-81) are too fragmented and their content is still waiting to be determined.

International Correspondence

The letters of this group can be divided into those exchanged between the great powers and the ones exchanged between independent kingdoms.

- Independent kingdoms: There are only two places in this category, which is Arzawa (EA 31-32) and Alashiya (EA 33-40). Arzawa was located on the south Anatolian coast. The alliance with Egypt was made via diplomatic marriage. Alashiya was on Cyprus and was known as a source of copper.

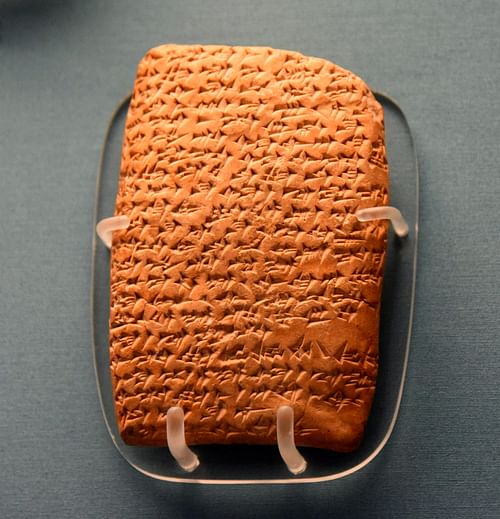

- Great powers: They were an exclusive group in which kingdoms were treated equally. They were the most influential and prosperous territories. Egypt only entered this group after the campaigns of Thutmose III. The others were Babylon, Hatti, Mitanni, and Assyria. As they were equals, they had a “brotherly” relationship and had to employ a specific pattern when writing to each other. At first, they had to identify who was writing and for whom the letter was written, then, report their wishes to the other, as shown in the example below:

Say to Naphurreya, the king of Egypt, my brother, my son-in-law, whom I love and whom loves me: Thus Tushratta, Great King, the king of Mitanni, you father-in-law, who loves you, your brother. For me all goes well. For you may all go well. For Tiye, your mother, for your household, may all go well. For Tadu-Heba, my daughter, your wife, for the rest of your wives, for your sons, for your magnates, for your chariots, for your horses, for your troops, for your country, and for whatever else belongs to you, may all go very, very well. (EA27).

The rest of the letter was less stereotypical, making requests or listing the items being sent. But, as we said, normally, they presented both requests and gifts. The most common subjects were negotiations of diplomatic marriage, friendship statements, and exchanged materials.

Vassal Correspondence

During the reign of Thutmose III, the Egyptian army went as far as the Euphates, establishing an empire in Canaan. These territories became vassals of Egypt, and some examples are Amurru (EA60-67, 156-71), Byblos (EA 68-138, 362, 139-40), Damascus (EA 194-97), and Qadesh (EA 189-190).

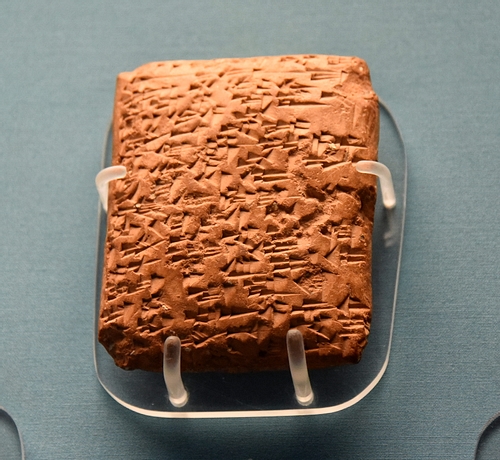

The Egyptian vassals referred to the Pharaoh as “my lord” or “my Sun” and usually began the letters in a pattern similar to the example below:

Say to the king, my lord, the Sun: Message of Rib-Hadda, your servant. I fall at the feet of my lord 7 times and 7 times (EA85).

Vassals, in theory, must obey their lords, and although the Egyptian vassals constantly declared and affirmed loyalty to the Pharaoh, some of them were traitors, negotiating with the Hittites, as did Qadesh and Amurru. Others, as Byblos and Damascus, were truly loyal to Egypt but were repressed by the traitors.

The Letters Today

As noted above, there are 382 tablets known to us, however, they were not found at the same time, which means that different groups of archaeologists and universities have discovered various portions. Thus, the tablets are nowadays spread all over the world. They can be seen in museums like the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin), the British Museum (London), the Louvre (Paris), and the Egyptian Museum (Cairo).

In 1992 CE, William Moran translated the 350 letters into English for the first time. Thanks to his book, The Amarna Letters, the correspondence can be easily explored by researchers from all over the world, given that, until then, only the version in cuneiform was available. In 2014 CE, a new edition of the letters was published by Anson F. Rainey and edited by William M. Schniedewind and Zipora Cochavi-Rainey. The book, The el-Amarna Correspondence, has translations, cuneiform transcriptions, and commentaries on the letters.