The Amarna Period of ancient Egypt was the era of the reign of Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), known as 'the heretic king'. In the 5th year of his reign (c. 1348 BCE), he issued sweeping religious reforms which resulted in the suppression of the traditional polytheistic/henotheistic religious beliefs of the culture and the elevation of his personal god Aten to supremacy.

According to some scholars, the period is limited to Akhenaten's reign while others claim it extends through the time of Akhenaten's successors and ends with the ascent of the pharaoh Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE). This latter claim is the one most commonly favored by mainstream scholarship, and the era is, therefore, most often designated as between c. 1348-1320 BCE.

Akhenaten's religious reforms are considered the first true expression of monotheism in world history and have been praised and criticized in the modern era by scholars arguing for and against the so-called 'heretic king'. The Amarna Period is, in fact, the era of ancient Egypt's history that has received the most attention because Akhenaten's reign is seen as such a dramatic departure from the standard of the traditional Egyptian monarchy.

Following Akhenaten's reforms, the temples of all the gods except those for Aten were closed, religious observances either banned or severely repressed, and the capital of the country was moved from Thebes to the king's new city of Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna). Akhetaten was essentially a city built for the god, not the people, and this reflects the central focus of Akhenaten's reign.

After embracing his new religious belief and suppressing that of others, Akhenaten more or less retreated to his god's city where he assumed the role of god incarnate and dedicated himself to the worship and adulation of his heavenly father, Aten. The lives of his people, trade contracts and alliances with foreign powers, as well as maintenance of the country's infrastructure and military, all seem to have become secondary concerns to his religious devotions.

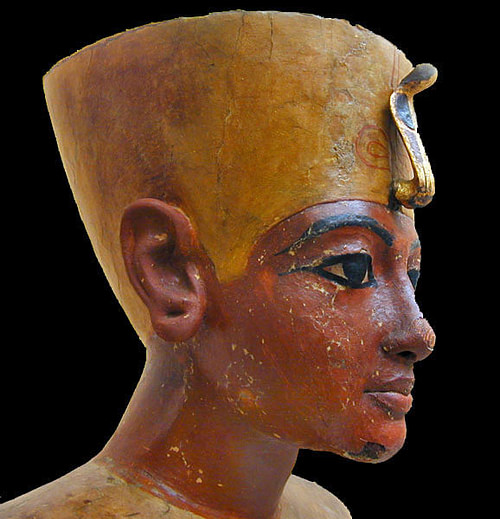

The religious reforms he instituted would not last beyond his death. His son and successor Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327 BCE) reversed his policies and brought back traditional religious practices. Tutankhamun's efforts were cut short by his early death but were continued, with far greater zeal, by one of his successors, Horemheb who destroyed the city of Akhetaten and erased Akhenaten's name from history.

Akhenaten & the Gods of Egypt

Akhenaten was the son of the great Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) whose reign was marked by some of the most impressive temples and monuments of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) such as his palace, his mortuary complex, the Colossi of Memnon who guarded it, and so many others that later archaeologists believed he must have ruled for an exceptionally long time to have commissioned them all. These grand building projects are evidence of a stable and prosperous reign which allowed Amenhotep III to leave his son a wealthy and powerful kingdom.

At this time, Akhenaten was known as Amenhotep IV, a name taken by Egyptian monarchs to honor the god Amun and which means 'Amun is Content' (or 'Amun is Pleased'). Amenhotep IV continued his father's policies, was diligent in diplomacy regarding foreign affairs, and encouraged trade. In his fifth year, however, he suddenly reversed all of this behavior, changed his name to Akhenaten ('Effective for Aten'), abolished the traditional belief structure of Egypt, and moved the capital of the country from Thebes (center of the Cult of Amun) to a new city built on virgin ground in middle Egypt which he named Akhetaten ('Horizon of Aten', but also given as 'Place Where Aten Becomes Effective'). Precisely what motivated this sudden change in the king is unknown, and scholars have been writing about and debating this question for the past century.

Akhenaten himself does not give any reason for his religious transformation in any of his inscriptions – even though many remain extant – and seems to have believed that the reason for his sudden devotion to a single god was self-evident: this was the one true god human beings should acknowledge, and all the others were either false or far less potent. However clear he may have felt his reasons to be, however, they were not understood that same way by his court or the people.

The ancient Egyptians – like any polytheistic society – worshipped many gods for a simple reason: common sense, or at least that is how they would have viewed their position. It was easy enough to see that in one's daily life a single person could not meet an individual's every need – one interacted with teachers, doctors, one's spouse, one's boss, co-workers, father, mother, siblings – and each of these people had their own unique abilities and contributions to one's life.

To claim that one person could fulfill an individual's every need – that all one required in life was just this one other person – would have seemed as absurd to an ancient Egyptian as it should to anyone living in the present day. The gods were viewed in this exact same way in that one would not think of asking Hathor for help in writing a letter – that was the area of Thoth's expertise – and one would not pray to the literary goddess Seshat for aid in conceiving a child – one would consult Bes or Hathor or Bastet or others who were divine experts in that area.

The gods were an integral part of the people's lives, and the temple was the center of the city. The temples of ancient Egypt were not houses of worship for the people but the earthly homes of the gods. The priests did not exist to serve a congregation but to care for the statue of the god in its home. These temples were often enormous complexes with their own staff who cooked, cleaned, brewed beer, stored grain and other surplus food, copied manuscripts, taught students, served as doctors, dentists, and nurses, and interpreted dreams, signs, and omens for the people.

The importance of the temples was felt far outside the complexes in that they generated and supported entire industries. The harvest and processing of papyrus depended largely on the temples as did amulet makers, jewelers, those who made shabti dolls, weavers, and a host of others. When Akhenaten decided to close the temples and abolish the traditional religious beliefs, all of these businesses suffered for it.

In the present day, when monotheistic understanding is commonplace, Akhenaten is often regarded as a visionary who saw beyond the confines of his religion and recognized the true nature of God; but this far from how he was perceived in his time. Further, it is quite likely that his reforms had less to do with a divine vision and were more an attempt to wrest power from the Cult of Amun and reclaim the wealth and power they had accumulated at the expense of the crown.

The King & the Cult of Amun

The Cult of Amun first gained power in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when the kings of the 4th Dynasty rewarded the priests with tax-exempt status in return for their diligence in performing mortuary rituals and maintaining the proper rites at the royal pyramid complex at Giza and elsewhere. Even a cursory study of ancient Egyptian history from this period forward makes clear that this particular cult was a perennial problem for the nobility in that they only grew more wealthy and powerful year after year.

Since they paid no taxes in the form of grain grown on their lands, they were able to sell it as they wished. The kings of the 4th Dynasty had also granted them enormous and fertile tracts of land in perpetuity, and this combination enabled them to accrue incredible wealth, and that wealth translated to power. In every one of the so-called 'intermediate periods' in Egyptian history – those eras in which the central government was weak or divided – the priests of Amun remained as powerful as ever, and in the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE), the Amun priests of Thebes ruled Upper Egypt with a greater display of power than the kings of Tanis (in Lower Egypt) could muster.

There was no way a successive king could reverse the policies of the Old Kingdom without undercutting the authority of the monarchy. A king in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, for example, could not claim that Khufu of the Old Kingdom had made a mistake regarding the Amun cult without admitting that kings, including himself, were fallible. The king was the mediator between the gods and the people who maintained the most important aspects of the culture, and so the king could not be seen as anything less than perfectly divine. The only way a king would be able to reclaim the wealth given away to the priests was to abolish the priesthood, to make them seem less than worthy of their position and power, and this is the course Akhenaten pursued.

Even in Amenhotep III's prosperous reign there is evidence of conflict between the priests of Amun and the crown and the minor solar deity known as Aten was already venerated by Amenhotep III along with Amun and other gods. It may have been Amenhotep III's wife (and Akhenaten's mother), Tiye (1398-1338 BCE) who suggested the strategy of religious reform to her son.

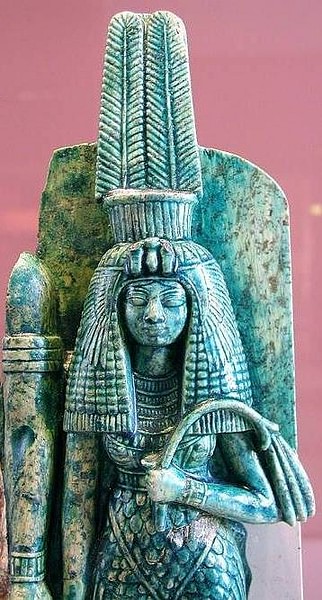

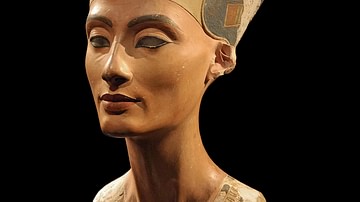

Tiye exerted significant influence over both her husband and son and, through them, the court and bureaucracy of Egypt. Her support of Akhenaten's reforms is well documented, and as a savvy politician, she would have recognized them as the only means to elevate the power of the pharaoh at the expense of the priests. Some scholars have also suggested Akhenaten's famous queen Nefertiti (c. 1370 - c. 1336 BCE) as the inspiration for the reforms as she also clearly supported and participated in the new faith.

A number of scholars over the years have claimed that Akhenaten's religious reforms were not monotheistic but simply a suppression of the activity of other cults to elevate that of Aten. This claim makes little sense, however, if one is aware of that same kind of initiative in Egypt's past. Amun was elevated to the height of king of the gods, and his temple at Karnak was (and still is) the largest religious building ever constructed in history. Even so, the cults of all the other gods were allowed to flourish just as they always had.

One cannot claim that the religious initiatives of Akhenaten were along the same lines as the earlier one of the priests of Amun; they were not. Akhenaten's Great Hymn to the Aten - as well as his religious policies - made clear that there was only one god worth worshipping. The Great Hymn to the Aten, written by the king, describes a god so great and so powerful that he could not be represented in images and could not be experienced in any of the temples or cities across the nation; this god needed his own new city with his own new temple, and Akhenaten would build it for him.

Akhetaten

The city of Akhetaten was the fullest expression of Akhenaten's new vision. It was constructed c. 1346 BCE on virgin land in the middle of Egypt on the east bank of the Nile River, built midway between the traditional capitals of Memphis to the north and Thebes to the south. Boundary steles were erected at intervals around its perimeter which told the story of its founding. On one of these, Akhenaten tells the story of how he chose the location:

Behold, it is Pharaoh, who found it – not being the property of a god, not being the property of a goddess, not being the property of a male ruler, not being the property of a female ruler, and not being the property of any people. (Snape, 155)

The new city could not belong to anyone prior to Aten. In the same way that the god was to be understood in a new light, so his place of worship had to be entirely novel. Amun, Osiris, Isis, Sobek, Bastet, Hathor, and the many other gods had been worshipped for centuries at different cities sacred to them but Akhenaten's god needed a site where no god had been venerated before.

The four main districts were the North City, Central City, Southern Suburbs, and Outskirts. The North City was laid out around the Northern Palace which was dedicated to Aten. Throughout Egypt's history the king and his family lived in the palace, and Akhenaten himself would have grown up in the enormous and luxurious palace of his father at Malkata. At Akhetaten, however, the royal family lived in apartments to the rear of the palace, and the most opulent rooms, painted with outdoor scenes depicting the fertility of the Delta region, were dedicated to Aten who was thought to inhabit them. In order to welcome Aten to the palace, the roof was open to the sky.

The Central City was designed around the Great Temple of Aten and the Small Temple of Aten. This was the bureaucratic center of the city where the administrators worked and lived. The Southern Suburbs were the residential district for the wealthy elite and featured large estates and monuments. The Outskirts were where the peasant farmers lived who worked the fields and built and maintained the nearby tombs in the necropolis.

Akhetaten was a carefully planned engineering wonder with enormous pylons at its entrance, an awe-inspiring palace and temples, and wide avenues down which Akhenaten and Nefertiti could ride in their chariot in the mornings. It does not seem to have been designed with the comfort or interests of anyone but themselves in mind, however. Since the land had never been developed before, any of the other people who lived and worked there would have had to have been uprooted from other cities and communities and transplanted at Akhetaten.

The Amarna Letters

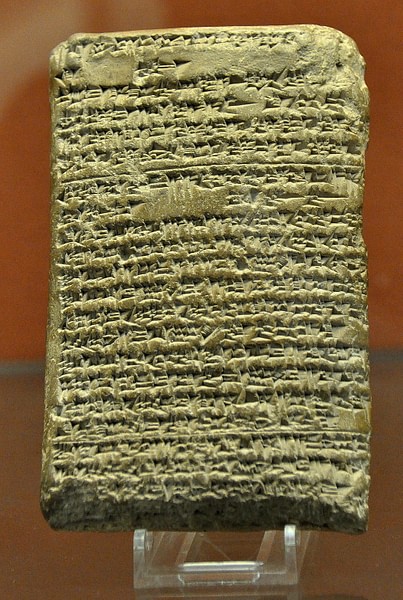

The area of the Central City has been of greatest interest to archaeologists since the discovery of the so-called Amarna Letters in 1887 CE. A local woman who was digging in the mud for fertilizer uncovered these clay cuneiform tablets and alerted the local authorities. Dating from the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, these tablets were found to be records of Mesopotamian rulers as well as correspondence between the kings of Egypt and those of the Near East.

The Amarna Letters have provided scholars with invaluable information on life in Egypt at this time as well as the relationship between Egypt and other nations. These tablets also make clear how little Akhenaten himself cared for the responsibilities of rule once he was ensconced in his new city. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom expanded the borders of the country, formed alliances, and encouraged trade through regular correspondence with other nations. These monarchs were keenly aware of what was happening both beyond and within Egypt's borders. Akhenaten chose to simply ignore whatever happened beyond the borders of Egypt and, it seems, anything beyond the boundaries of Akhetaten.

Foreign rulers' letters and appeals for help went unheeded and unanswered. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson notes that Ribaddi (Rib-Hadda), king of Byblos, who was one of Egypt's most loyal allies, sent over fifty letters to Akhenaten asking for help in fighting off Abdiashirta (also known as Aziru) of Amor (Amurru) but these all went unanswered and Byblos was lost to Egypt (112). Tushratta, the king of Mitanni, who had also been a close ally of Egypt, complained that Amenhotep III had sent him statues of gold while Akhenaten only sent gold-plated statues. There is evidence that Queen Nefertiti stepped in to answer some of these letters while her husband was otherwise engaged with his personal religious rituals.

Amarna Art

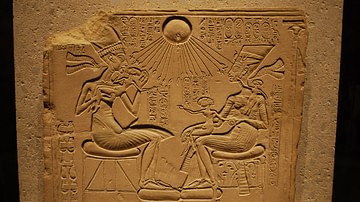

The transformative nature of these rituals is reflected in the art of the period. Egyptologists and other scholars have often commented on the realistic nature of Amarna Art and some have even suggested that these depictions are so accurate that the king's physical infirmities can be detected. Amarna art is the most distinctive in all of Egypt's history and its difference in style is often interpreted as realism.

Unlike the images from other dynasties of Egyptian history, works from the Amarna Period depict the royal family with elongated necks and arms and spindly legs. Scholars have theorized that perhaps the king "suffered from a genetic disorder called Marfan's syndrome" (Hawass, 36) which would account for these depictions of him and his family as so lean and seemingly oddly-proportioned.

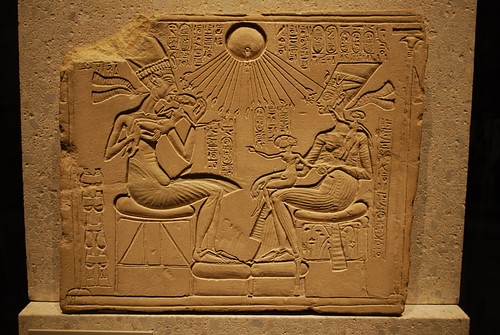

A much more likely reason for this style of art, however, is the king's religious beliefs. The Aten was seen as the one true god who presided over all and infused all living things through life-giving, transformative rays. Envisioned as a sun disk whose rays ended in hands touching and caressing those on earth, Aten not only gave life but dramatically changed the lives of believers. Perhaps, then, the elongation of the figures in these images was intended to show human transformation when touched by the power of the Aten.

The famous Stele of Akhenaten, depicting the royal family, shows the rays of the Aten touching them all and each of them, even Nefertiti, depicted with the same elongation as the king. To consider these images as realistic depictions of the royal family, afflicted with some disorder, seems to be a mistake in that there would be no reason for Nefertiti to share in the king's supposed syndrome. The claim that realism in ancient Egypt art is an innovation of the Amarna Period is also untenable. The artists of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) initiated realism in art centuries before Akhenaten.

Tutankhamun & Horemheb

These artworks were created to adorn the tomb of the king and his family in the city of Aten. Akhetaten was designed as the god's home in the same way that the gods' individual temples had once been built. Akhetaten was created to be grander than any of these temples and, in fact, more opulent than any other city in Egypt. Akhenaten seems to have attempted to introduce Aten to the great Temple of Amun at Karnak early in his reforms but these attempts were unwelcome and encouraged him to build elsewhere. Every aspect of the city was carefully planned by the king and the architecture was designed to reflect the glory and splendor of his god.

Akhetaten flourished throughout Akhenaten's reign but, after his death, was abandoned by Tutankhamun. There seems to be evidence that the city was still operational through the reign of Horemheb, notably a shrine to that pharaoh found on site, but the capital was moved to Memphis and then back to Thebes.

Tutankhamun in the present day is best known for the discovery of his tomb in 1922 CE but, after the death of his father, he would have been respected as the king who restored the ancient religious beliefs and practices of the land. The temples were reopened and the businesses which depended on them began to operate as they used to. Tutankhamun did not live long enough to see his reforms through, however, and his successor (the former vizier Ay) carried them on.

It was the pharaoh Horemheb, though, who finally restored Egyptian culture fully. Horemheb may have served under Amenhotep III and was commander-in-chief of the army under Akhenaten. When he came to the throne, he made it his life's mission to destroy all trace of the Amarna Period.

Horemheb razed Akhetaten and dumped the ruins of the monuments and stelae into pits as fill for his own monuments. So thorough was Horemheb's work that Akhenaten was wiped from Egyptian history. His name was never mentioned again in any kind of records, and where his reign needed to be cited, he was referred to only as "the heretic of Akhetaten".

Conclusion

Horemheb considered his former king worthy of what has come to be known as the Damnatio Memoriae (Latin for 'condemnation of memory') in which all memory of a person is erased from existence. Although this practice is most commonly associated with the Roman Empire, it was first practiced in Egypt centuries earlier through inscriptions known as Execration Texts. An execration text was a passage inscribed on ostraca (a shard of a clay pot) or sometimes on a figure (along the lines of a voodoo doll) and often on a tomb warning would-be robbers of the horrors which awaited them should they enter uninvited.

In the case of Akhenaten, the execration text took the physical form of completely eradicating his memory from history. He had inscribed his name and that of his god at the Temple of Amun at Karnak; these were erased. He had erected other monuments and temples elsewhere; these were torn down. He had replaced the name of Amun at the Temple of Hatshepsut with the name of Aten; this was changed back. He had built a grand city on the banks of the Nile surrounded by inscriptions which told the story of its building, its builder, and his god; this was razed to the ground. Finally, Horemheb backdated his reign in official inscriptions to that of Amenhotep III to completely blot out the memory of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and the vizier Ay.

Akhenaten's name was lost to history until the 19th century CE when the Rosetta Stone was deciphered by Jean-Francois Champollion in 1824 CE. Excavations in Egypt had unearthed the ruins of Akhenaten's monuments used as fill, and the site of Akhetaten had been mapped and drawn early in the 18th century CE. The discovery of the Amarna Letters, along with these other finds, told the story of the ancient 'heretic king' of Egypt in the modern age where monotheism has become accepted as a natural, and desirable, evolution in religious understanding.

In this age, Akhenaten has often been hailed as a religious visionary and hero who took the first steps, even before Moses, in trying to enlighten people to the true nature of God. Akhenaten is a staple example of a proto-Christian, according to some understandings, who – centuries before the Christian era – recognized the reality of a deity unlike his creations, one who dwells in "light inaccessible" (Isaiah 55:8-9 and I Timothy 6:16). This respect for the ancient king and his reign, however, should be recognized as a modern development based upon a modern-day understanding of the nature of divinity.

In his day, and for centuries after, Akhenaten and the Amarna Period were unknown to the people of Egypt and for a very good reason: his religious initiatives had thrown the country off balance and disrupted the core cultural value of harmony between the gods, the people, the land they lived in, and the paradise of the afterlife they hoped to enjoy eternally. A present-day understanding might see Akhenaten as a religious hero but to his people he was simply a poor ruler who allowed himself to forget the importance of balance and fell into error.