Amastris (c. 340/39-285 BCE) was a niece of the Persian king Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) through her father Oxyathres. She was married in succession to Alexander's general Craterus, the tyrant Dionysius of Heraclea, and finally to Lysimachus of Thrace. She founded an eponymous city in Paphlagonia and was the first queen to issue coins in her own name. Amastris was the mother of four children, was supposedly divorced so that Lysimachus could marry Arsinoe II, and was allegedly murdered by her sons for interfering in their affairs. Despite their divorce, Lysimachus still avenged her death by killing her sons. Scholars have mostly ignored Amastris and left the few known details of her life as contradictory as the ancient sources present them. Yet, the little-known queen is arguably the first true Hellenistic queen as she embodies the entanglement of Persian and Greco-Macedonian traditions.

The Last Achaemenid Princess

As the daughter of prince Oxyathres, the brother of the last Persian king Darius III Codomannus, Amastris was in effect the last surviving Achaemenid princess. Although her mother is unknown, the only woman associated with her father is an Egyptian concubine called Timosa. After the Battle of Issus (333 BCE), Alexander the Great found Amastris among the other royal and noble women. During the grand wedding ceremony at Susa almost a decade later (324 BCE), when the Macedonian high commanders were married to Persian and Median women, Alexander gave Amastris to his general Craterus – the only companion besides Hephaestion to wed a Persian princess. Historians maintain that Craterus, famously devoted to Macedonian tradition, repudiated Amastris in order to marry Phila, the daughter of the Macedonian regent Antipater. As Macedonian royalty and nobility practiced polygamy, Craterus did not have to separate from one wife to marry another. Craterus, at any rate, would soon fall in battle (321 BCE).

Dionysius of Heraclea

The ancient historian Memnon actually implies that Amastris was not abandoned, as she offered herself in marriage to the tyrant Dionysius of Heraclea Pontica (c. 360-305 BCE) – with Craterus' consent. She would bear Dionysius three children, named Amastris, Clearchus, and Oxyathres. The given names are significant as they exemplify her high standing as Persian princess. Amastris would be able to offer Dionysius valuable information about the inner workings of the Persian nobility, she had received a Greek education in the years before the Susa wedding ceremony, and she may have acquired a fair impression of the affairs in Macedon through her first husband.

Dionysius took advantage of his marriage to further expand his sphere of influence in Bithynia – as he had been doing since the Battle at the Granicus (334 BCE) and the eventual collapse of Persian power. Indeed, in the same passage the ancient historian Memnon writes that, through his marriage with Amastris, Dionysius was able to greatly increase his good fortune and wealth, to strengthen and expand his power, and to improve the welfare and goodwill of his subjects.

Shortly before his death, Dionysius followed Antigonus I Monophthalmus (382-301 BCE) and the other successors by laying claim to the title of basileus ('king'; c. 306/5 BCE). The nature of his death was apparently a popular cautionary tale against wanton luxury and gluttony, for the story is preserved in Athenaeus, Aelian, and Photius (all three accounts likely go back to Nymphis of Heraclea, who was Dionysius' near-contemporary). It is said that Dionysius died at the age of 55 from asphyxiation as a result of his enormous obesity after his physicians had tried keeping him alive by piercing him with large needles. Before his death (c. 305 BCE), Dionysius had installed Amastris as regent for their underage sons Clearchus and Oxyathres. Initially, she ruled with the support of Antigonus, until he became heavily distracted by the grand coalition formed against him by the successor kings Cassander (c. 355-297 BCE), Ptolemy I (366-282 BCE), Seleucus I Nicator (358-281 BCE), and Lysimachus (c. 355-281 BCE).

Lysimachus of Thrace

Amastris remained in power at Heraclea for three years. Meanwhile, Lysimachus had been assigned to Thrace after Alexander's death (323 BCE); he claimed kingship like the other successors (c. 305 BCE) and then aimed to expand his dominion. He thus crossed the Hellespont and invaded Asia Minor in 302 BCE. At the end of the campaign season, the ancient historian Diodorus relates:

Lysimachus divided his forces to go into winter quarters in the plain of Salonia. He sent after many supplies from Heraclea, having made an additional marriage with the Heracleotes; for he had wed Amastris, […] who was dynast of the city at that time. (Diod. 20.109.6-7.)

Evidently, their marriage was political as both stood to gain from their marital alliance. For Amastris, the advantage of switching her allegiance from Antigonus to Lysimachus was foremost to secure her own position and that of her children by avoiding the annexation of Heraclea.

Lysimachus, for his part, was in need of support against Antigonus. Marriage precluded a military confrontation and the need for garrisons in the region. Amastris could also offer him her treasury, not to mention further diplomatic relations with the Persian nobility and a symbolic connection to the Achaemenids, which Lysimachus might eventually require to strengthen his position against Seleucus. Heraclea also provided Lysimachus a harbor in the Black Sea with control of access routes from the east and the west. To be sure, Lysimachus was already married – and was explicitly acknowledged to be polygamous. Like the other Macedonians, Lysimachus, a close friend of Alexander and one of the highest commanders in the army, must have received a bride at the Susa wedding ceremony; he later married Nicaea, Antipater's younger daughter, around the time of the Settlement at Triparadisus (320/19 BCE).

After the Battle of Ipsus (301 BCE), in which Antigonus was killed, Lysimachus summoned Amastris to the Lydian capital, Sardis. Her son Clearchus was established as ruler of Heraclea Pontica in succession to his father and would later share power with his younger brother Oxyathres. The extent to which they were able to retain a measure of autonomy from Lysimachus is debatable. It might be assumed that Amastris would join Lysimachus at his court in Thrace, though there is no supporting evidence. Soon (c. 300/299 BCE), he would additionally marry Arsinoe, a daughter of Ptolemy I of Egypt. Most scholars maintain that Lysimachus was serially monogamous, and thus divorced Amastris. It is true that Amastris did eventually return to Heraclea from which it might be deduced that she had separated from her third husband.

From Bithynia to Paphlagonia

Queens did not normally leave the king's court; wives were expected to remain with their husbands. Amastris, however, had at least initially resided at Sardis, and Arsinoe II was later installed by Lysimachus as his royal representative in Ephesus. It would actually have been in Lysimachus' best interest to retain Amastris, and it could be suggested that (like Arsinoe later in Ephesus) Amastris was established on the Pontic coast to rule on her husband's behalf. Moreover, her son Clearchus joined Lysimachus' campaign against the Getae (Thracian tribes located along the Lower Danube; c. 293/2 BCE). Such an alliance seems unlikely if Lysimachus had repudiated Clearchus' mother several years before.

Amastris' return to Heraclea upset her sons' standing because her presence meant that she regained control of the city. She could hardly have done so without Lysimachus' consent. She is indeed said to have revived the city upon her arrival. She then personally founded a new city in her own name (present-day Amasra) beyond the River Parthenius (Bartın Çayı) on the Paphlagonian coast between Heraclea and Sinope. What is more, Amastris issued spectacular silver coinage in her own name with the reverse legend “Basilissês Amastrios.” Although the word basillisa more broadly denotes 'royal woman,' here it can only mean 'queen.'

While Phila, the wife of Demetrius I of Macedon (c. 336 - c. 282 BCE), was the first woman to receive the title basilissa (c. 305/4 BCE), these were the first coins ever to be issued in the name of a queen or any living woman and should thus be interpreted as a bold statement of female authority. It would be remarkable, to say the least, if the Persian Amastris reigned independently – that is, as female sovereign, rather than a king's wife. She was royal by birth, Dionysius had claimed kingship shortly before his death, and Lysimachus had likewise laid claim to kingship. It appears, then, that Lysimachus had arranged for Amastris to rule as queen along the Paphlagonian coast.

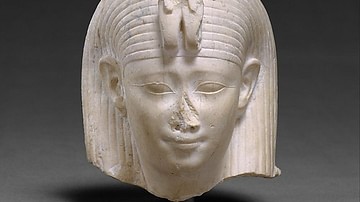

The obverse of Amastris' silver staters features a vigorous youthful head, wearing a Phrygian or Persian-type cap, decorated with a laurel wreath and on posthumous issues a star with eight rays; on some of the earliest issues a bow and quiver can be seen behind the nape of the neck. The portrait has been variously attributed to Attis, Men, Mithras, Perseus, and Amastris herself or her Amazonian namesake. A veiled female figure, dressed in a pleated garment, seated on a pillowed throne, cradling a floral scepter to her left is presented on the reverse. In the palm of her outstretched right hand, she either holds a little winged Eros or a Nike. The Eros figurine offers a ribbon to a radiate head of Helios above; the Nike figurine offers the woman a wreath.

The headdress on the youthful portrait represents a Persian cap rather than the Phrygian type. This cap appears regularly on the satrapal coinage of the Achaemenid Empire. The obverse of Amastris' coinage thus expresses the queen's right to rule as the king's representative but does so in Persian terms and thus proudly proclaims her royal heritage.

Death & Aftermath

It is unknown how many years passed after Amastris returned from Lysimachus' court, had taken over control in Heraclea, founded a new city, and issued coinage of at least ten subtypes that proclaimed her authority (though somewhere between five and ten years seems likely). Her sons Clearches and Oxyathres must have failed to reach an accommodation with her and Lysimachus. Perhaps as an act to proclaim their independence, the brothers murdered their mother by drowning at sea. At Amastris' death (c. 285 BCE), Lysimachus arrived at Heraclea as if to approve the succession of Clearchus and Oxyathres, showing his usual 'friendship' and 'fatherly affection.' He then avenged Amastris' death by having the matricides killed. Lysimachus replaced the Heraclean tyranny with a democratic government and placed the city under his direct protection. He carried away the tyrants' treasures and returned to Thrace.

Marital relations at dynastic level discussed here served pragmatic, diplomatic, and political, rather than personal purposes, despite the ancient sources' repeated claims to the contrary. Alexander and his successors did not marry for the sake of love, although affection or attraction might have played its part. The belief in romance severely impedes our understanding of Hellenistic dynastic practices. The ancient and modern notion about the supposed serial monogamy of the kings is, moreover, seriously misguided.

Like the other successors, Lysimachus was involved in propagating his dynastic glory by dotting the landscape of his kingdom with settlements named after himself and his wives. These cities include Lysimachia in Thrace (modern Gallipoli), Nicaea in Bithynia, and Arsinoea on the site of Ephesus, in addition to the city of Amastris. City foundations served symbolic and ideological purposes, in addition to economic and military functions. Founding cities across the kingdom and circulating coins in his wives' names was a dynastic policy to enhance the glory of his royal family. The policy meant to increase the presence of his power and augmented the appearance of his wives' influence.

In sum, Amastris rose to power and prominence in the early 3rd century BCE and was in a very true sense the first Hellenistic queen. Other royal women received the title basilissa before her, perhaps – notably Phila and Apama – but no other Hellenistic queen founded cities or issued coins before her, and none were of royal Persian descent. Reviewing the surviving, though contradictory, evidence allowed for a reappraisal of the life of Amastris. Rather than a pawn in dynastic marital games, her remarkable career and the circumstances of her death present her as a formidable agent who was invaluable for the men she married. Lysimachus, whose royal aim certainly was to enlarge his kingdom as far as possible, more generally employed his queens as representatives of his power. Amastris, moreover, seems to have promoted her Persian heritage with pride.

A version of this article was originally published at AncientWorldMagazine.com.