The Amphictyonic League was an early form of religious council in ancient Greece. It was typically composed of delegates from several tribes or ethnes living in the vicinity of a major, prosperous sanctuary, who then collaborated in supervising the temple's maintenance, managing its finances, organising the sacred rituals and games, and seeing to the protection of its temenos (sacred precinct).

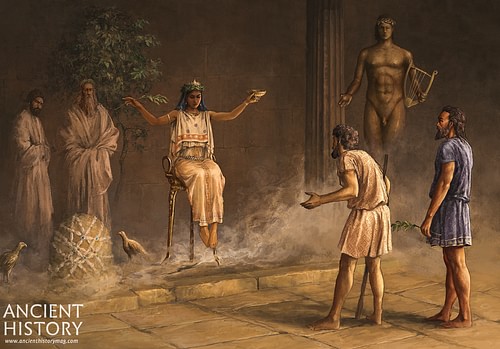

The earliest evidence about the existence of such executive assemblies appears in the 7th century BCE, and the most significant and best-documented examples are the Amphictyonic Leagues of Delos and Delphi, both presiding the sanctuaries of Apollo, his Pythian Oracles, and the Pythian Games.

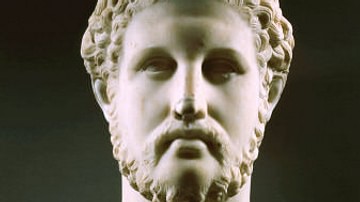

While the Amphictyonic League was primarily a religious organization, it sometimes played a significant role in the political and military affairs of ancient Greece. The League's most notable involvement in Greek warfare occurred during a series of conflicts known as the Sacred Wars over control of the Delphic sanctuary. These conflicts had a dramatic impact on the course of Greek history and the development of the poleis (city-states), fostering changes that eventually cushioned the ambitious plans of Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE), and his son Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), for conquering the Hellenic world.

Origins & Structure

The exact origins of the Amphictyonic League are wrapped in myths and legends, but it is generally agreed that, by the 7th century BCE, the gathering of a council of tribal representatives to look after their local sanctuary was a practice already recognised in Archaic Greece (c. 800-480 BCE). According to Herodotus (8.104) and Pindar (Pythian Odes, 4.66, 10.8), the Greek word amphictiones (άμφικτίονες) means "those who dwell around," implying the solidarity among neighbouring tribes through their connection with and their care for a pivotal sacred place.

In Greek mythology, Amphictyon, the legendary founder of the league, was a son of Deucalion and Pyrrha, the surviving couple of the Great Flood in the Greek version of the story, and the younger brother of Hellen, whose name became the overall denomination of the Greek people as Hellenes (Graecus, the eponym of the Graecians as the Romans called the Greeks, was the son of Zeus and Pandora). Following the flood, Amphictyon with his family took refuge in Athens, where he became the son-in-law and later the successor of King Cranaus. Amphictyon then became king of Thermopylae near Phthiotis in Thessaly, where his brother Hellen was the ruler. Since Cranaus, Deucalion, and many other legendary Greek founder-rulers were believed to be chthonic, born of Mother Earth, the earliest Amphictyonic council was then formed to protect and provide for the sanctuary of Demeter Amphictyonis in Anthela, Thermopylae, since Demeter was the goddess of the underworld in her older cults.

Based on this inherent connection to the underworld, members of the Amphictyonic council (pylaia) were known as the pylagorai, guardians of the gate to the underworld. A second, and superior, group of the delegates were the hieromnemones, sacred recorders, who had the power to finalise the debated decisions by casting votes (Aristotle, Politics 8.6). The pylaia met twice a year, once in spring at Delphi and once in autumn at Anthela. Their agenda, essentially, covered the matters considering the maintenance and protection of the sanctuary, which typically consisted of a central temple (and often some related side temples, shrines, and altars), the temenos, and the treasury. Organising and supervising the sacred rituals held at the sanctuary, including public games and competitions, was another important task of the Amphictyonic Council.

Although presumed more or less ubiquitous, there are only a few Amphictyonies known to us apart from the ones at Delos and Delphi: the Amphictyony of Onchestos near Thebes in Boeotia dedicated to the temple of Poseidon, the Amphictyony of Amarynthos in Euboea tending the sanctuary of Artemis, and the Amphictyony of Kalauria, an island near the coast of Troezen. The latter, also related to the cult of Poseidon, was claimed by Strabo (8.6.14) to be one of the earliest in the Archaic times – functioning at least until the end of the 4th century BCE – and archaeological evidence accordingly places its foundation between c. 680 and 650 BCE. On the other hand, an alternative legend accounts for the unification of the guardian councils of the Demeter Amphictyonis and the Apollonion at Delphi as the Great Amphictyonic League in the aftermath of the Trojan War, c. 1200 BCE. Historically, however, the great Amphictyonic League at Delphi was founded no earlier than c. 590 BCE. It is the best-documented council of its kind and has the longest remaining history, not least because of its pivotal role in the Sacred Wars.

Sacred Wars

The First Sacred War (c. 595-585 BCE) was fought between the Amphictyonic League and the city of Krisa (or Krissa), one of the oldest cities in Greece. The exact location of Krisa is still waiting to be discovered, but it was certainly somewhere southwest of Delphi by Mount Parnassus in Phocis. The war broke as a result of a dispute between Delphi and Krisa over their respective portions of profits obtained through their guardianship in situ of the Delphic Oracle and its treasury, the Pythian Games, and other ensuing bonuses and benefits. Krisa wanted to impose a tax on the pilgrims and visitors, and Delphi was mindful of the rapid economic growth in Krisa. Votes were taken for the final decision, and the delegates from Krisa found themselves in the minority against the representatives of Athens, Sicyon, and Thessaly, all siding with Delphi. The conflicts disputably lasted around 10 years, presumably the duration of the siege laid on the city of Krisa whilst blocking its port at Kirrha. The Amphictyonic allies finally poisoned a major water source of the city with hellebore, leaving the defenders and the rest of the population weakened with diarrhoea. With the city thus captured, the allies razed Krisa to the ground and killed most of the inhabitants, dedicated its lands to the Apollonian sanctuary but as sanctioned from any use.

Despite this tragic end for Krisa, the First Sacred War brought important advancements for the Amphictyonic League at Delphi – its delegation expanded from 3 to 12 allying city-states, its precincts and wealth multiplied, the variety of competitions in the Pythian Games levelled up from one to many, securing a place among the quadrennial Panhellenic games, and, most importantly, the council was hailed to a position of significance among the Greek states. The Oracle at Delphi was regarded as a sacred tenet belonging to and functioning for all Greeks. Delphi's protection and prosperity, therefore, had the highest priority and importance. When the Phocians invaded Delphi in 449 BCE, they were confronted with and defeated by no other than Sparta in the Second Sacred War.

The Third Sacred War (356-346 BCE) was perhaps the most significant in the League's history, as it had profound consequences for the balance of power in Greece. This war was triggered when the Phocians seized the Delphic sanctuary to protest the heavy fines exacted on them by the Amphictyonic League for farming in the sacred lands taken from Krisa. Soon enough, they were joined by Athens and Sparta as powerful allies, whilst Thebes, Thessaly, Locris, Doris, and Boeotia sent military forces to help the Delphian Amphictyony. With the Apollonian treasury in their possession, the Phocians managed to hold on to their controlling position at Delphi whilst fighting back the Amphictyonic forces. The next decade thus witnessed the expansion of war to different parts of the Greek soil, including Thessaly, Locris, Doris, Boeotia, Euboea, and Peloponnese.

The exhaustion of financial sources at Delphi and the inconclusive struggles between all combating forces from both sides cried for a pacifying iron fist. Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE), with his background of military and diplomatic education as a royal hostage in Thebes, one of the mightiest city-states, had already managed to defeat all the opponents of Macedonia, expanding his kingdom by conquering their lands and beyond. In 354 BCE, Philip was asked by the Thessalians to help the Amphictyony in a crucial battle. His game-changing victories encouraged further requests for help, which in turn paved his way to successive conquests whilst earning the leadership of various leagues of allying city-states. He eventually defeated and uprooted the Phocians and was duly rewarded with almost unquestionable supremacy over the Amphictyonic League. Soon after, Philip compelled the Athenians to sign a submissive peace treaty with him, then successfully invaded and destroyed the Spartan hegemony over the Peloponnese. Philip's military and political triumphs and subsequent control over the League thus marked the rise of the Macedonian power in Greece.

The Fourth Sacred War, in fact, was the escalation of a strict resistance against Philip's accumulative power led by Demosthenes and his anti-Macedonian faction in Athens. Open hostilities started in 339 BCE, when Philip was appointed as chief executioner of Amphissa, near Delphi, which was again charged for cultivating the sacred and sanctioned lands taken from Krisa. Philip destroyed the city, then turned with full force to face Athens, Thebes, and other city-states who had come to retaliate and stop his ruthless advances. The conflicts resulted in their decisive and crippling defeat by Philip and his son, Alexander, at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE – a terminating point for Athenian democracy, independence, and authority.

Decline & Legacy

With the ever-growing Macedonian predominance in Greece, and eventually, after the death of Alexander the Great, the subsequent division of his Hellenistic Empire during the Wars of the Diadochi between Macedonia, the Seleucid Empire, Ptolemaic Egypt, and some other kingdoms, the influence of the Amphictyonic League began to wane along with the autonomy of individual Greek city-states. At any rate, the Amphictyony had already violated the oaths taken by its members in many cases. Aeschines (2.11.5) tells us that the oath was verbally supposed to safeguard the associated cities against being ruined and deprived of accessing water supplies. Whereas Krisa and Phocis had been dealt with by the destruction of their cities while their inhabitants were killed by poisoned water or, in the case of Phocis, forcibly scattered in small villages.

Still, the Amphictyony continued to exist during the Hellenistic period and even well into the Roman era, although with its power limited, again, to religious matters and no perceptible political activity in the shadow of Macedonian and then Roman rule. In 279 BCE, the Gauls invaded Greece as a part of their expansionist attempts to exploit the opportunities that emerged from the prolonged power struggle in the Macedonian Hellenistic Empire after Alexander. Their invasion was rebuffed by a remarkable alliance of the Greek city-states, and the Amphictyonic League at Delphi applauded their victory by re-admitting the Phocians as well as adding the Aetolian League. The Amphictyony received a respectful reconfirmation under Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) with minor changes, and eventually in 131 CE, it was replaced with the Panhellenion by Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), which did not last more than a year.

The Amphictyonic League was a significant institution in ancient Greek history, illustrating the complex interplay between religion, politics, and diplomacy in the classical world. While its primary function was religious, the League's involvement in military and political matters had far-reaching consequences for the development of the Greek administrative system. The Amphictyony may well have served as a pre-draft of the democratic model of rulership, gathering an assembly of people's representatives to discuss public affairs and to make decisions by casting votes, hundreds of years before the establishment of the earliest democratic procedures in Classical Greece.