Amphipolis, located on a plain in northern Macedonia near Mt. Pangaion and the river Strymon, was an Athenian colony founded c. 437 BCE on the older Thracian site of Ennea Hodoi. Thucydides relates that the Athenian general Hagnon so named the town because the Strymon surrounds the site on three sides ("amphi" means "on both sides") and also relates that he built a fortification wall on its unprotected side. The city and its seaport, Eion, prospered due to its favourable geographic location and the proximity of abundant natural resources, especially gold, silver, and timber. In 2012 CE an impressive Hellenistic tomb was discovered, one of the most important archaeological finds of the last 40 years, which has, once more, put Amphipolis in the lime-light.

Historical Overview

The Spartan general Brasidas conquered the city in 424 BCE and defeated Cleon when Athens attempted to retake Amphipolis two years later. In the latter battle, Brasidas had brilliantly employed his peltasts to defeat the larger Athenian hoplite army, but the Spartan leader himself eventually succumbed to his wounds. The great military commander was buried in the city's agora and honoured with annual games. Amphipolis came back under Athenian control following the Peace of Nicias in 421 BCE; however, the Amphipolitans, in the event, opted to remain an independent polis (city-state) and in 367 CE made an alliance with the Chalcidian League. In 364 BCE the Athenians, still as eager as ever to guarantee their grain supply from the Black Sea, once more tried to make themselves masters of strategically important Amphipolis, this time led by the general Timotheos and with the initial encouragement of the Macedonian king Perdiccas III, who ruled Amphipolis at that time. Unwilling in the end to hand over the city, Perdiccas established a garrison there, and on his death, Macedonian control fell to his successor, Philip II.

Although now a Macedonian city, Amphipolis did retain some degree of independence and many of her political institutions such as a demos or popular assembly, remained intact. Over time, as more and more Macedonian colonists settled in the polis, Philip, and later his son Alexander the Great, used Amphipolis as a base from which to attack Thrace and Asia. Probably a Macedonian administrative capital, the city was also the site of the most important Macedonian mint where, amongst others, the famous gold staters were produced. The site has also been a source of documentation regarding Macedonian military regulations. We are informed that soldiers who displayed great courage on the battlefield should be given a double share of the booty, that a general should ensure his army does not devastate a defeated territory by burning grain or destroying vines, and that soldiers must have their equipment in order, not sleep on guard duty, and report such failures amongst their comrades to their superior. Transgressors could be fined and those who reported them received a bonus.

When Rome conquered Macedon in 168 BCE, Amphipolis retained some importance as one of the four regional capitals. The city was an important stopping point on the via Egnatia highway which connected Greece to Asia. The city acquired impressive fortifications, especially around the ancient acropolis, measuring over 7,000 metres long and over 7 metres high in places. Augustus conferred the status of civitas libera, making it a free city and the emperor was even given the title of Ktistes or founder. In later times, from c. 500 CE, Amphipolis became the seat of an episcopal see, and no fewer than four basilicas attest to the religious importance of the site in Late Antiquity. The site was abandoned in the 8th and 9th centuries CE following the Slavic invasions after which citizens of Amphipolis relocated to nearby Eion which survived into the Byzantine period. Amphipolis was again settled in the 13th to 14th centuries CE, from which period the remains of two towers survive.

Archaeological Remains

Excavations of Roman Amphipolis have revealed traces of all the impressive architecture one would expect from a thriving Roman city. A bridge, gymnasium, public and private monuments, sanctuaries, and cemeteries all attest to the city's prosperity. From the early Christian period (after 500 CE) there are traces of four basilicas, a large rectangular building which may have been a bishop's residence, and a church.

Basilica A was a three-aisled basilica with two floors and two rows of ten columns down its length. It was constructed on the site of a Roman bath. Parts of the marble flooring, some polychrome mosaics of wildlife, pieces of a hexagonal platform, and two rows of seats of the synthronon survive. Basilica B originally measured 16.45 x 41.6 metres, and it too had marble decoration and mosaics. Basilica C dates to the second half of the 5th century CE and had two interior colonnades of six columns, of which the bases survive, as do mosaics of various geometric and wildlife designs. Basilica D is contemporary with Basilica C and had a marble and brick flooring; 15 column bases and various mosaics also survive.

The large rectangular structure which may have served as an episcopal palace measured over 48 metres wide and had walls 1.3 metres thick. Three cisterns in the southwest corner constructed using waterproof cement survive. Another building of interest is the early Christian church which included a large hexagonal chamber surrounded by a circular wall. The 6th-century CE church had two floors with colonnades and much of the interior was tiled with marble, including the mosaic-tile flooring. Finally, two Byzantine towers either side of the Strymon River survive. The best-preserved is the north tower which was built in 1367 CE and which stands 10 metres tall and originally had three stories. Both towers offered some protection to the nearby monastery on Mt. Athos.

The Amphipolis Tomb

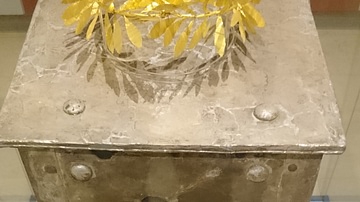

The 4th-century BCE burial mound at Amphipolis was discovered in 2012 CE, and it is one of the most important archaeological finds of the last 40 years. It has a surrounding wall measuring almost 500 metres in circumference and constitutes the largest burial site ever found in Greece. The scale and impressive architecture of the tomb, which uses marble imported from Thassos, suggest the occupant was a person of great importance. An almost intact skeleton has been discovered within a wooden coffin placed in a limestone tomb in the third chamber of the complex. The chief archaeologist at the site, Katerina Peristeri, stated that the tomb dated to after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE) and, "in all probability belongs to a male and a general". Artefacts from the complex include a large stone lion (discovered in 1912 CE but now thought to have once stood atop the mound), two caryatids, two sphinxes, and a large pebble mosaic measuring 4.5 by 3 metres which depicts the god Hades abducting Persephone in a chariot led by Hermes. Historians and enthusiasts alike eagerly await the findings of the on-going research on the Amphipolis tomb and to discover just who was buried in such a splendid tomb.