An amphora (Greek: amphoreus) is a jar with two vertical handles used in antiquity for the storage and transportation of foodstuffs such as wine and olive oil. The name derives from the Greek amphi-phoreus meaning 'carried on both sides', although the Greeks had adopted the design from the eastern Mediterranean. Used by all the great trading nations from the Phoenicians to the Romans, the sturdy-walled amphora spread throughout the ancient world and they have become an important survivor in the archaeological record providing clues as to dates of sites, trade relations, and everyday diet.

Designs

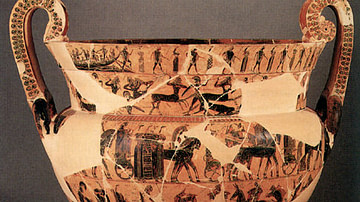

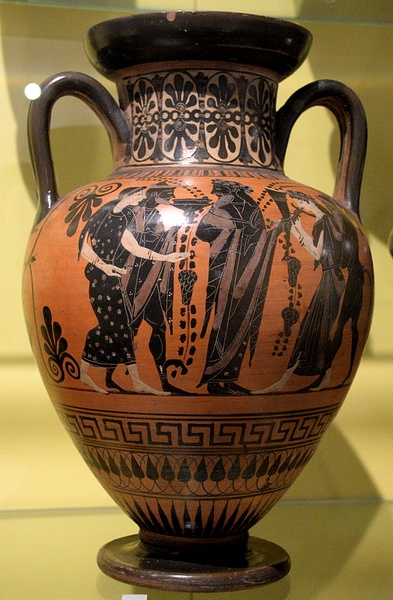

Evolving from the large Bronze Age pithoi vessels, which the Minoans and Mycenaeans used for storage purposes, the amphora became perhaps the most common ancient pottery shape. However, the size and form had a great many variations. Amphorae could also be plain – typically when used for the transport of goods – or highly decorated, just as any other red-figure or black-figure pottery. Specific places, already noted for their pottery production, such as Corinth and Attica, along with famed wine-producing islands like Chios, Lesbos, and Samos all produced distinctive amphora types. So too did colonies in the Black Sea area and Magna Graecia, although some cities were happy enough to copy tried and tested designs. All amphorae were made in stages on the wheel with a period of drying between the addition of a new section.

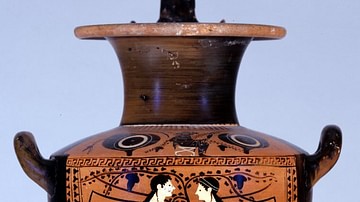

The two basic types of amphora were the neck-amphora, which has the shoulder joining the neck at a sharp angle, and the belly amphora (or simply amphora) which curves continuously from neck to foot. Those vessels with broad mouths were known as either kadoi or stamnoi while the plain types for transport were referred to as amphoreus. Gradually the form of the vessel evolved to reflect its primary function as a carrier of wine and for ease of packing. The base foot became a spike and the vessel overall became taller and slimmer. In addition, during the Roman period the contents of amphorae became easily identifiable from the shape of the vessel in question, a useful feature when stored in busy ports. Decorative amphorae with a pointed base would have been kept upright in a bronze stand or deep ceramic ring.

Functions

The average capacity for amphorae was 20-25 litres, although early versions were considerably larger. The general size became limited by the necessity for one or two persons to easily carry the vessel, and a standardisation, although attempted, was not achieved in practice until the Byzantine period. Foodstuffs transported in them included wine, olive oil, honey, milk, olives, dried fish, dry food such as cereals, or even just water. Non-food contents included pitch, and some were used in tombs as containers for the ashes of the deceased. Another special type was the Panathenaic amphora which was a large vessel of around 36 litres decorated with black-figure designs. They were filled with olives and given as prizes in the Panathenaic Games, held every four years in Athens. Finally, miniature amphorae known as amphoriskoi (sing. amphoriskos) or pelikai (pelike) were used for storing perfume.

The Romans used amphorae in much the same way as the Greeks but with the addition of such Roman staples as fish sauce (garum) and preserved fruits. For this reason, amphorae were sealed using clay or resin stoppers, some also had a ceramic lid when used to store dry goods. Very few lids have survived in proportion to amphorae but those that do commonly have a single knob handle, sometimes made into the shape of a fruit. Finally, amphorae were used for completely unrelated purposes to their original design such as burial whole in marshy land to provide more solid foundations for buildings and walls or in roof domes as a means to provide additional support between courses.

Stamps

Many amphorae (but certainly not all) used to transport goods were given a stamp before firing, typically placed on the neck, rim, or handles. This identified the place of origin (pottery workshop), indicated the vessel was part of a particular batch, named a controlling official, or guaranteed the content volume and quality. The name or monogram of the manufacturer might appear on the stamp, a month, or a regional adjective or symbol (Rhodes, for example, used a rose emblem). In the case of wine, the age of good wine was indicated and the drink-by-date (year) for cheap wine. Stamps were also a means by which authorities could exercise a control on customs duties. Stoppers could be stamped for the same purpose. In addition to stamps, the Romans painted information labels on their vessels to make their contents easily identifiable.

All of this information has often been invaluable for archaeologists when attempting to date a site which contains amphorae, especially shipwrecks. Finally, the discovery of amphorae whose origin can be identified and their quantities are helpful in determining the extent of trade in the ancient world. The Monte Testaccio in Rome is an artificial mound of pottery shards coming from some 53 million discarded amphorae; impressive testimony to the fact that the amphora was one of the most common and useful objects in antiquity.