Art, along with language, is perhaps the best way to see the connections between the ancient peoples we label as Celts who lived in Iron Age Europe. There were great variations across time and space but common features of ancient Celtic art include sculptures of enigmatic gods and naked warriors, a love of depicting forest animals, the use of complex and swirling vegetal designs, and a desire to enhance the beauty of even the smallest and most mundane of everyday objects. Celtic art was both influenced by and eventually retreated from neighbouring cultures ranging from the Thracians to the Romans. In vogue ever since ancient and medieval pieces were rediscovered in the 19th century CE, Celtic art continues to fascinate and inspire artists and craftworkers today.

Themes in Celtic Art

Although there is much debate amongst scholar as to the utility of the term ‘Celts’ to refer to various peoples across Iron Age Europe, the one area which is perhaps most convincing that there were ties of cultural similarity across the continent is in the art these people produced. From Iberia to Bohemia there were repeated themes in art, which appeared in various media from 700 BCE to 400 CE. Naturally, there were many regional variations in art, but some of the ideas which crop up again and again in Celtic art include:

- the love of flowing forms, both in the contours of artworks and in their decoration.

- depictions of gods and warriors, particularly the heads of these.

- depictions of animals (real or imagined), especially of the forest such as stags, boars, horses, and hunting dogs.

- the use of complex vegetal designs, abstract patterns, and swirling interlocking lines, which can fill every available decorative space on an object.

- the appearance of art in all types of objects including functional everyday items for cooking and in miniature form such as tiny hairpins.

- the desire to convey messages of power and religious ideas concerning this life and the next.

Another source of variation besides space and time is the external cultures which particular groups of Celts came into contact with in terms of neighbours, trade, and war. Greek and Etruscan pottery was greatly appreciated, for example, and has been found in many Celtic burial sites. Elements of Thracian art and that of the Scythians can also be seen in Celtic art such as bulls heads and ornate drinking horns. When the Romans conquered Gaul in the second half of the 1st century BCE, they brought with them ideas in art, particularly a love of fantastic creatures and new materials like brass and enamel. Via trade and diplomatic gifts, even the artistic ideas of such far-flung places as Persia made their way to Celtic Europe. Celts also learnt from each other, with some regions specialising in certain art forms such as the goldsmiths of the regions around the Rhine and Moselle rivers. Finally, with the Christianisation of Europe, Celtic art adopted new forms and media, best seen in the illuminated manuscripts, brooches, and stone crosses which typify medieval Celtic art.

To add to the difficulty of appreciating art which was produced over many centuries in different regions, the Celts left very few written records and so we have no commentaries from the creators themselves on what inspired their art, what their art was intended to represent, or how it was to be used. Consequently, Celtic art must be judged largely by examining only the art objects themselves and the contexts in which they have been rediscovered. It is also well to remember that in ancient cultures there was no categorisation of ‘high art’ and craftwork. For the Celts, art could be applied to anything and it was always functional, even if only the wealthy could afford highly decorated items like ornate vessels for feasting, armour, and weapons. It is for all of the above reasons that the historians J. Farley and F. Hunter state: "Celtic art is a difficult and complex label" and "it is more correct to understand it as a series of 'Celtic arts' rather than a single, homogenous tradition" (205 & 51).

Celtic Sculpture

Sculpture was carved from wood, stone, and metal, such as cast or hammered bronze, iron, and gold. Extra form and decoration were achieved via engraving, punching, tracing, and repoussé (grooving the material from behind to create a relief on the other side). Details were added to sculptures of all kinds using colourful materials such as glass (especially red), coral, shell, amber, semi-precious stones, and enamel.

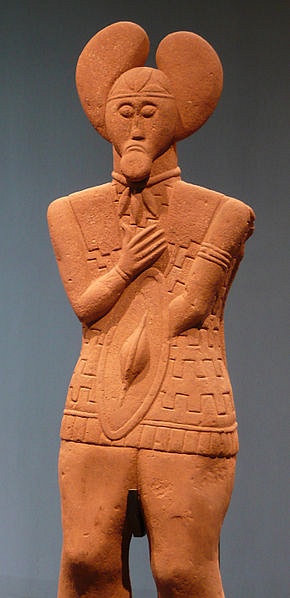

Early Celtic sculptures focus on the human form, especially heads, which were considered the home of the soul. Such works usually represent gods and heroic warrior figures but are often abstract, with typical facial features being lentoid eyes, a bulbous nose, and swept-back hair. Sculptures are rarely life-size, but some examples do survive. The horned god Cernunnos, who represented nature and fertility, appears in various stone sculptures. Wooden standing figures, especially from oak, are depicted wearing a hooded cloak and were sometimes given a metal torc to wear around their necks. These figures likely stood at Celtic religious sites.

Another form that had religious connotations is the carved stones which survive from France and Ireland, in particular. Typical stones are shaped into domes or four-sided pyramids and are covered in abstract designs of lines, swirls, and vegetal motifs. They may have represented a Celtic view of the universe and been placed at sacred sites. A fine example is the 5th-4th-century BCE stone pillar from Pfalzfeld, St. Goar, Germany. The pillar is 1.48 metres (4 ft 8 in) tall and was once topped by a head. Divided into four sides by vertical cable reliefs, each face has a human head with a beard and wearing a headdress known as a ‘leaf crown’, a motif that appears repeatedly in Celtic art.

It was the warrior, though, who seems to have really captured the Celtic imagination. Often depicted naked and wearing only a torc around the neck, a sword belt and sometimes a cloak, warrior figures were made in all sizes and were perhaps made to stand at burial sites. A life-sized example is the 5th-century BCE 'Prince of Glauberg', excavated from Glauberg, Germany. The warrior, who carries a shield, is wearing a mail tunic and a torc necklace with three pendants. He also wears an elaborate headdress of the ‘leaf crown’ type. Then there are sculptures which we cannot positively identify as either a god or a warrior. The most famous example is the sandstone Mšecké Žehrovice Head from a sanctuary in the Czech Republic, which dates to around the 2nd century BCE.

Animals, both real and imagined, were another favourite subject, especially in miniature form in metal to adorn all manner of objects such as cauldrons, chariots, and jugs. The Celts believed that animal totems, especially on weapons, armour, as helmet crests, on war horns, and on shields, all protected the wearer and instilled in them the properties and characteristics of particular animals. Frequently represented animals - either whole, their heads, or as masks - include the bull, horse, stag, and boar. A fine piece of abstract Celtic sculpture, once meant to adorn a bucket or similar vessel, is the 50 BCE - 100 CE bronze horse head mask which was discovered as part of the Stanwick Hoard of North Yorkshire, England. The mask is made from a single metal sheet and has highly stylized eyes, nostrils, and nose bridge, all rendered in shallow relief. Another technique to create obscurity was to design a piece so that it changed when viewed from different angles. From the side a face might appear merely as a group of interconnected lines and shapes and only from front-on is the abstract face of a human or animal revealed.

Celtic Shields

Sculptures of Celtic warriors often have them carrying their familiar oblong shield, and these items, in particular their bosses, were often themselves a work of art. Celtic shields were made of wood and leather with buckles in metal, with a central boss for added strength. These bosses and bronze ceremonial shields or the bronze facings intended for real shields were another opportunity for the Celtic artist to display their skills. An outstanding example is the Battersea Shield, now in the British Museum. The shield was recovered from the River Thames and was likely thrown in its waters as a votive offering. Dating to between 350 and 50 BCE, the shield is made from sheet bronze which is decorated with reliefs, engravings, and repoussé work. There are three large roundels with a pronounced central boss in the central and largest roundel. There are scrolls and 27 framed studs once filled with red glass paste. Palmettes and S-shaped motifs in repoussé connect the studs within each roundel.

Two pieces which display abstract Celtic art are the Witham Shield and the Wandsworth Shield Boss, both also recovered from English rivers. The central boss of the Witham Shield, which dates to 400-300 BCE, has abstract repoussé decoration with the addition of red coral pieces. The shield has a faint design of a male boar with elongated legs, visible today only as a difference in the shade of patina. The Wandsworth Shield Boss dates to the period 350 to 150 BCE. The decoration on the boss takes the form of stylised birds' heads with hooked beaks and elongated bodies in repoussé. The extremities of the birds morph into scrolls or tendrils as the two creatures seem to fly around the circumference of the shield boss. This type of decoration can be seen in other Celtic works like bronze mirrors and ritual helmets.

Celtic Torcs

The torc is one of the quintessential items of Celtic jewellery and was noted by Classical writers as a distinguishing cultural feature (even if they did exist in other cultures, too). Examples abound of warriors and gods wearing neck torcs in Celtic art, but plenty of examples of the real thing have survived, too. This may be because the torc was offered in rituals or because they were buried as handy a store of wealth. Torcs may have had a spiritual significance, may have protected the wearer, and been an indication of the wearer’s status; gold ones must surely have been a symbol of wealth. Made from iron, bronze, copper, silver, and gold, the design varies in terms of the terminals which can be loops, animal heads, or shapes like hourglasses, spheres, and disks. The rope can be plain, twisted, solid, hollow, or wrapped around an organic core.

Perhaps the finest example of a Celtic torc is the Snettisham Great Torc, part of the Snettisham burial hoard found near the village of Snettisham in Norfolk, England. Made using a gold alloy (the other metals are silver and copper), it weighs a little over one kilo (2.2 lbs) and dates to 150-50 BCE. The band of this neck torc is composed of 64 strands which are twisted into eight ropes, each comprising eight strands. The terminals are hollow and were cast using moulds and welded to the ropes. The terminals mix embossed areas with chased 'basketwork', the craftworker using very fine tools to achieve this and to sharpen up the cast work and remove any imperfections.

Another very fine example is the silver-plated Trichtingen torc, discovered near the town of that name in Germany and likely dating to the 2nd century BCE. Measuring 29.5 cm (11.5 in) in diameter and weighing 6.7 kilos (14.8 lbs) it is too heavy to be worn and so was either made as a votive offering or once adorned a statue. The terminals in the form of bull’s heads imitate the art of Thrace or Persia.

Celtic Brooches

The ancient Celts were particularly fond of creating ornate brooches and pins. Needed for the practical function of holding clothing together, brooches soon developed from plain bronze and iron fibulae into highly ornate status symbols and amulets worn by men, women, and children. Earlier brooches might take the form of animals, especially horses and snakes but also human heads, bells, and drums. They could be S-shaped with a head at either end or be more abstract with spirals and intricate knots. A common shape was the penannular brooch which was composed of an almost complete ring and a pin that could turn and pass through the break for opening and closing. The penannular brooch became highly decorative and was popular across Europe through the Middle Ages.

The finer examples of Celtic brooches were made using gold and could be inlaid with colourful precious materials. The metal was cast, engraved, and punched. One of the greatest examples of these miniature masterpieces is the Braganza brooch, discovered in Spain and dating to 250-200 BCE. This gold brooch has a Celtic warrior complete with a shield who is facing a hunting dog. The highly decorative pin guard has intricate loops and curves.

Celtic Cauldrons

Cauldrons held a special place in Celtic culture; they represented abundance and regeneration, while in mythology, they have magical properties like producing never-ending portions of food. Cauldrons used for special occasions like Celtic feasts were especially ornate. Made from sheet bronze, they were suspended over fires via chains and used to cook meat stews. Miniature sculptures often adorned the rims, handles, and points of suspension.

The greatest example of a decorative cauldron, perhaps too well-made to have ever been used for cooking, is the Gundestrup Cauldron from Denmark. This partially gilded silver bowl perhaps dates to the 1st century BCE or earlier and was likely imported from the lower Danube region. The splendid relief panels show scenes of Celtic-inspired gods, but there are, too, motifs and animals seen in Near Eastern art. As the historians J. Farley and F. Hunter note, the cauldron "is not Celtic, or, at least, not just Celtic" (262). As such, it is an object that continues to intrigue, and it epitomises the difficulties in examining just what is and what is not ancient Celtic art. Five inner and eight outer panels show gods identified as Cernunnos and Medb, amongst others, most of whom wear a neck torc. There are scenes of a bull sacrifice, a troop of Celtic warriors, winged griffins, leopards, and elephants.

Celtic Pottery

Celtic pottery vessels are very often elegantly curved in form and may be dark in colour or red with black decoration. Early vessels copied those items made in bronze. Despite their simplicity, vessels were well-made and highly polished. A typical 6th-century BCE vessel type is the tripartite carinated vessel made from three separate and angular pieces. With the introduction of the faster potter’s wheel from the Mediterranean, better-quality vessels became possible. The Celts were particularly fond of wine, and a type of flask with a long neck, known as the Linsenflasche, was common in central Europe in the 5th and 4th century BCE. Bulbous vessels with a small pedestal and no handles abound from the mid-4th century BCE onwards.

Simple geometric designs were popular on early pottery. As the art form became more sophisticated, animals were a favourite motif for decoration and could be incised, painted, or stamped onto pottery of all kinds. Curvilinear decoration was another common feature as Celtic artists filled all available spaces, a tendency which further emphasised the curves of the vessel. On occasion, a large area of a vessel is painted plain to bring into focus a neighbouring area of decoration. The combination of animal silhouettes and flowing geometric lines is best seen in the pottery of southern France in the 2nd century BCE when the animals become almost unrecognisable with their elongated bodies and limbs.

Decline & Legacy

The spread of the Roman Empire from the 1st century CE saw Celtic culture and art absorb more Mediterranean ideas, not only in modes of representation but also the very subject of art. A bas-relief from Rheims shows centre-place given to the figure of Cernunnos but either side of him stands the Greco-Roman gods Apollo and Mercury. Further, mass-produced Roman art and the erosion of the Celtic system of patronage of indigenous art caused by the new political and social order meant that Celtic art began to go into decline and all but disappear in continental Europe. Then, as Christianity gripped Europe in late antiquity, so European artists modified their works to reflect people’s new beliefs. Celtic artists, confined now to Britain and Ireland, found expression for their ideas in brooches, particularly the penannular type, which carried symbols within its decoration relevant to the Christian religion. Meanwhile, the love of complex curvilinear designs found a new home in illuminated manuscripts while sculptors created ornate stone crosses for cemeteries.

In effect, Celtic art fused with Anglo-Saxon and Viking art in medieval Britain but remained purer in more isolated Ireland and Scotland. With the Norman conquest of England in 1066 CE, a whole new raft of influences arrived and art moved on once again to new ideas and materials. Consequently, the art produced by the ancient Celts now became an obscure element of the unwritten past. Then, after centuries, came the return. Celtic art enjoyed a great revival in the 19th century CE following the miraculous discovery of several important pieces such as the Hunterston and Tara penannular brooches and the wider interest in pre-Roman history. Inspiring artists with its abstract and curvilinear forms, the art of the ancient Celts, very often encouraged by ideas of nationalism and rejuvenating cultural heritage, rose once again to prominence and echoed within such movements as Art Nouveau.