The polytheistic religion of the ancient Celts in Iron Age Europe remains obscure for lack of written records, but archaeology and accounts by classical authors help us to piece together a number of the key gods, sacred sites, and cult practices. Variations existed across regions and the centuries, but common features of the Celtic religion include the reverence for sacred groves and other natural sites like rivers and springs, the dedication of votive offerings to gods such as foodstuffs, animal and (more rarely) human sacrifices, and the depositing of valuable and everyday goods with the deceased in tombs. With a religion led by druids who were loath to commit their knowledge to writing, there are no sacred texts, hymns or prayers which survive in written records. There are also significant gaps in our knowledge such as the Celtic view of their own origins, the universe and their place within it, and the ultimate fate of their world. Nevertheless, we do have, thanks to a combination of studies and methodologies, a reasonable if tantalisingly incomplete picture of the gods, beliefs, and religious practices of pre-Christian Europe.

The Celtic Gods

The ancient Celtic pantheon had over 400 gods, but these may not have been envisaged with human characteristics as was the case in, say, the ancient Greek religion. Neither can one really say there is a pantheon of universal gods worshipped everywhere speakers of the Celtic language lived. Rather, the Celts across Europe venerated some gods which were also venerated in other regions and those which were entirely local. To add further complexity to a subject already made difficult by a lack of extensive written records from the Celts themselves, the people of Iron Age Europe were influenced by the gods and religious practices of earlier and neighbouring cultures, but just how remains conjecture. Further, when the Roman Empire expanded across Europe, the Celts adopted and adapted many facets of the Roman religion.

We are on firmer ground when examining the role of certain gods in Celtic culture. Votive inscriptions, rituals, and burial practices indicate that the gods were thought to control humanity in some way, or at least have a strong influence on the welfare of people. They were often given all-embracing powers and a myriad of associations, many of which overlap with other gods, and this is a point of distinction between the Celtic religion and those of the contemporary Mediterranean cultures.

Celtic gods were associated with such phenomena or natural places as the sun, lightning, warfare, rivers, and particular tribes, settlements, and families. One of the widest-venerated gods was Lugus (who became better-known as Lugh in the Middle Ages). He may be the god that Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 BCE) describes as the supreme Celtic god, but scholars are not all in agreement on this point. He represents the sun and light and was regarded as an all-wise and all-seeing deity. Lugus gave his name to many places such as Lugdunum, modern Lyon in France.

Perhaps the god most depicted in Celtic art is Cernunnos, often described as simply 'the horned god'. Typically shown seated and wearing stag antlers or horns, he remains a mysterious figure. He is famously depicted on the Gundestrup Cauldron (perhaps 1st century BCE) where he wears torcs, another common association. Other major gods include Sequana, a healing goddess particularly venerated at the source of the River Seine in central France. Brigantia was an important goddess in Britain whom the Romans equated with Nike/Victory. The goddess Epona was worshipped across Europe and associated with horses, Esuss with his hammer-like staff was perhaps a patron of crafts, and Rhenus was the god of the Rhine river.

Several gods were viewed as a trio, perhaps representing three different aspects of the same divinity, an example being the three mother goddesses, the Matronae who represent individually the similar concepts of strength, power, and fertility. Of the many local and regional gods, many were associated with those things of primary concern to everyday ancient Celtic society such as warfare, sovereignty, tribal identity, healing, and the protection of specific groups like mothers, children, fishermen, and so on. Finding daily food was an obvious concern, and many deities are associated with hunting and with particular animals, especially those of the forest like boars and stags.

Besides gods, animals were also important to the Celts and were perhaps themselves regarded as sacred, especially the bull, boar, stag, and horse. Many of these animals were regarded as totems with protective qualities and so they appear frequently in designs on weapons and armour. Another source of protection was amulets, considered to protect both the living and the deceased on their journey into the Otherworld. Amulets were thought to ward of dangers (as opposed to talismans which bring luck) and are found in particular in the graves of children and women. Amulets could take unusual forms such as miniature wheels, shoes, feet, and axes.

Druids

The religious leaders in Celtic communities, and those regarded as intermediaries between humanity and the gods, were the Druids, a class of individuals known for their great wisdom and knowledge of traditions. Not only priests who managed all religious rituals such as sacrifices to the gods, druids were able to give practical help by interpreting events of nature, divining the future as soothsayers, and making medicinal potions, especially using sacred plants like mistletoe. Druids were repositories of the community's history and may also have been required to cast geissi or taboos (often less accurately called spells) on people, ensuring compliance to the society's rules and inclusion in community religious activities. Evidence that women were druids in antiquity is scarce, although there is no evidence, either, that they were prohibited from the role.

Druids, then, enjoyed a high status in Celtic society and may have emphasised their unique role by wearing long white robes and perhaps, too, unusual headgear such as helmets with horn or antler attachments. To become a fully-practising druid took a great deal of effort, some 20 years of training. The emphasis on oral learning between druids and novices has, unfortunately, meant that we have next to no first-hand written records of their activities. Roman writers, for example, often misinterpreted the role of druids and sometimes give fortune-telling duties to a separate class of individuals, the seers who interpret such things as flights of certain birds. Another figure sometimes equated with druids is the fili or learned poet-historian of ancient Ireland. Whether druids, seers, and fili were entirely separate individuals or could be found in a single individual is still much debated by scholars.

Druids had their own sacred places where they gathered at annual events. Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) mentions in his Gallic Wars such a site in the region of the Carnutes tribe in central France (around modern Orléans), and we know, too, that Mona (Anglesey, Wales) was considered a holy island for druids prior to the mid-1st century CE.

Sacred Sites, Sanctuaries & Temples

Natural sites of importance such as rivers, lakes, and bogs were held as sacred by the Celts as water was considered a conduit to the Otherworld. For this reason, springs and river confluences were considered especially sacred. Hilltops, mountains, and sacred groves of trees (nemeton), especially oaks, also hosted rituals and ceremonies. Even individual trees, particularly large oaks, could be held as sacred, and community elders gathered for assemblies under their shade. All of these places were considered potential meeting places between the physical and supernatural worlds.

Such sacred sites were often prepared in some way. In the more natural locations, this could be little more than a clearing, but nearer urban settings, they might have purpose-built earthworks, ritual gates, shrines, and temples added. The Celts likely also used megalithic structures that had been set up centuries earlier but they then developed their own unique religious architecture. One type of Celtic sacred area was a square or rectangular cleared area surrounded by earthworks. These are sometimes known as Viereckschanzen after a great number were discovered in southern Germany, even if they exist in one form or another at Celtic sites from France to Bohemia. The perimeter of the space was given a rampart, outer ditch, and a single gate (most often on the east side). The bare sacred space often had wooden poles driven into it, presumably for supporting a number of roofed structures and/or for carving symbols and images on. Some had deep shafts dug in them where votive offerings were placed. Pottery shards in these shafts most often date to the 2nd and the 1st century BCE.

Stone temples first appeared amongst the Celts from the 4th century BCE. Typically given monumental doorways decorated with reliefs and paintings, the roofing was made of thatch or intertwined branches which were then covered with clay and lime. For the Celts, the head was considered the home of the soul and so it is not surprising that masks were a common decoration of temples and even real human heads taken from sacrificial victims. After the Roman conquest, Celtic temples often adopted the design features of classical architecture.

Sacred sites were given statues and artworks representing gods, particularly tall wooden, often featureless figures wearing metal torcs and representations of heads. Gods were not commonly represented in stone it seems prior to the Roman conquest, a period that also saw standing stones carved into pillars and domes and decorated with reliefs of heads and vegetal designs.

Rituals, Offerings & Sacrifices

Rituals were held in accordance with a particular schedule based on the cycles of nature, astronomy, and, in particular, the phases of the Moon. Prayers and incantations were offered to the gods. Votive offerings were made at sacred sites to thank or appease the gods, or to gain their favour for future events or to avoid disasters like war, famine, and drought. Such offerings could take the form of foodstuffs, precious jewellery, decorated weapons and armour (particularly those taken from an enemy), or finely made pottery vessels, and, in the case of recovery from illness, small models of the sufferer or the affected part of the body. Often, precious objects were bent or broken before they were offered to the gods. Sacred sites near lakes, rivers, or bogs typically received goods thrown into the waters. Excavations at Anglesey, for example, revealed a mass of swords, shield bosses, spear points, cauldrons, decorative metal pieces for riding gear and chariots, slave chains which include collars, and a great number of animal bones.

Animals were sacrificed to the gods. Burned or buried intact at a site, oxen, bulls, dogs, and horses (or the leg of a horse) seem to have been the most common offering. There is, too, evidence that feasting went on where part of the animal was eaten before the remains were left to the gods. Humans were also sacrificed, much more rarely and very likely restricted to times of great stress to the community such as natural disasters or wars. Captured enemy warriors were likely the most common source. A possible sacrificial victim (not all scholars agree) is Lindow Man, a corpse discovered at Lindow Moss, a bog near Cheshire in England. Lindow Man lived no later than the turn of the 1st and 2nd century CE, and he was in good health. He died in what seems to have been a standard manner for ritual killings: hit on the head, strangled, and had his throat cut. The corpse was put in water for some time and then buried.

Other methods of human sacrifice, as described by Roman writers, were sometimes particular to specific gods. Victims for Teutates were drowned; for Esus, they were hung from a tree and had their limbs removed; and for Taranis, they were placed in a hollow tree or wooden vessel and burnt alive. The most elaborate of all methods (according to Strabo, c. 64 BCE - 24 CE), was to build a gigantic human figure using straw and wood, stuff it with cattle, wild animals, and humans, and then set the whole thing ablaze.

Both human and animal sacrifices were also used to divine future events. Victims were scrutinised as they died, and their death throes, the direction of flowing blood, and even their entrails were examined for particular signs.

Another type of offering, and one which has delighted intrepid amateur archaeologists, is the burial of hoards: precious goods buried in shallow pits. Typically, several items were bundled together such as broken or complete torcs, necklaces, and coins. Such deposits were often added to over a period of years, and the number of hoards found in close proximity to each other suggests that the general location was regarded as sacred in some way. For example, at the site of Hallaton in England, archaeologists discovered over 5,000 coins buried in 16 different places. The collective value of these goods and the number of deposits indicates they were not merely safe deposits but had some ritual meaning now lost.

Burial Practices

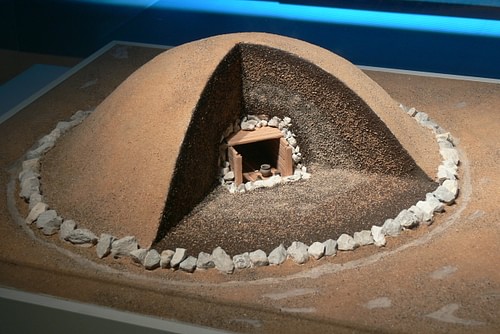

Archaeological evidence is strong that the Celts believed in an afterlife. Burials of rulers and elite individuals (both men and women) often have the deceased interred along with their personal possessions, weapons, armour, tools, eating utensils and paraphernalia for Celtic feasts, board games, extra clothing, foodstuffs, and precious objects like fine imported pottery or bronze vessel and gold jewellery. The deceased, if sufficiently important, was often placed in a wood-lined chamber deep within a large mound of earth. Within the inner chamber, the corpse was frequently laid out on a four-wheeled waggon (usually dismantled) or bench and dressed in all their finery. Burials in mounds could be for a single individual or have other occupants added later over time. Several mounds have been discovered in close proximity to each other at major Celtic settlements. Burials in flat graves gradually replaced the use of mounds.

The burial of objects with the deceased indicates a belief that they would need these things either on the journey to or upon reaching their final destination, or both. Our knowledge is limited but the Otherworld may have been considered like this life but without all the negative elements like disease, pain, and sorrow. Certainly, this was the view of Celts in medieval Europe. In this sense, then, there was little to fear from death when one’s soul departed one’s physical body.

Not all Celts were buried. Cremation became more common from the 2nd century BCE onwards, probably under influence from the Mediterranean cultures. Sometimes the cremated remains were then buried. Another alternative was excarnation - where the corpse was left exposed to the elements for a period and the bones then either buried or kept for future religious ceremonies.

Decline

From the 1st century BCE and the conquest of Gaul, the Roman Empire at first took a less aggressive stance against the Celtic religion, satisfying itself with robbing Celtic temples of their treasures. Statues of Roman gods appeared in Celtic temples and shrines, but some Celtic deities were adopted by the Romans, too, particularly members of the Roman army, and some sanctuaries were expanded. Then, during the 1st century CE, as the Romans sought to tighten their grip on conquered peoples, measures were taken to eradicate cultural leaders, notably the druids. Druidism was forbidden, and such important sanctuaries as the one on Anglesey were attacked and destroyed. Then, in late antiquity, there was something of a revival of the Celtic religion when the Roman Empire fell into decline and Christianity had yet to tighten its own hold on European religious practices.

Some of the ancient Celtic gods did survive and morph into new versions in unconquered Ireland and Scotland, as well as parts of Wales, but these seem not to have been directly worshipped as such, and they largely became humanised hero-figures in epic poems. The ancient pagan gods, made benign in harmless medieval literature, had become an acceptable face of a religion now lost. Ultimately, the Celtic religion was a victim of military and cultural conquest, a religion that could never be revived in its original form, despite spurious attempts from the 19th century CE onwards, for lack of written records.