Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE) was an Italian Renaissance artist most famous for his use of foreshortening and other perspective techniques in engravings, paintings, and frescoes. Another common feature of Mantegna's work is his frequent use of ancient Roman sculpture and architecture as a setting for his innovative presentation of familiar religious and mythological subjects. Amongst his most celebrated works are the cycle of frescoes in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua and such paintings as the Agony in the Garden and Lamentation of Christ, all triumphs of three-dimensional perspective in a two-dimensional medium.

Early Life

Andrea Mantegna was born in Isola di Cartura near Padua in northern Italy around 1431 CE. At a young age, Andrea was sent off to Padua to study under the artist Francesco Squarcione (1394-1474 CE). Squarcione, who became Andrea's adoptive father, was a noted artist in his own right, and he had a large workshop and impressive collection of ancient Greek and Roman art, two essentials for any ambitious Renaissance artist. Andrea must have learnt well from the 'father of painting' as he was entered into the Paduan guild of painters at the age of eleven.

Mantegna's work was influenced by such established artists as Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE), Paolo Uccello (1397-1475 CE), and Filippo Lippi (c. 1406-1469 CE). Another source of inspiration was Jacopo Bellini (c. 1400 - c. 1470 CE) but this relationship went beyond art when Mantegna married Bellini's daughter in 1453 CE. Bellini also possessed a great number of sketches of antiquities such as sculpture, funerary altars, coins and inscriptions. Mantegna, thus, combined an admiration of classical art with the elements of Roman architecture and sculpture he knew so well from Squarcione's workshop to become a Renaissance master.

The Mantegna Style

Mantegna's first work of note was the production of a series of frescoes in the Ovetari chapel of the Eremitani church of Padua. The artist worked on these scenes showing the lives of Saint James and Saint Christopher from 1449 to 1456 CE, but only two panels survive today in Venice. The other panels were ruined in a Second World War bombing raid, but fortunately, a photographic record had been taken. Even in this early work, Mantegna showed a certain originality and disregard for convention in religious art. For example, the patron of the Eremitani chapel, Ovetari's widow Imperatrice, sued Mantegna for not showing all the apostles in a scene depicting the Assumption of the Virgin. Another feature of the frescoes which would have surprised viewers at the time is Mantegna's decision to show some scenes as if being viewed from below, a sort of 'worm's-eye' view of the events.

Next came The Agony in the Garden, produced c. 1455 CE to c. 1460 CE and showing Jesus Christ at the moment of his arrest. The tempera on panel painting shows all the elements that would become Mantegna's hallmark: dramatic foreshortening of foreground figures, various perspective effects, a mixture of contemporary and classical architectural details, and an uncluttered overall composition.

The Agony painting, now in the National Gallery, London, is particularly interesting because the artist has achieved a sense of depth without using any straight lines, a trick then commonly employed by contemporaries to draw the eye of the viewer into the painting. Instead, Mantegna has used a series of sweeping curves to create three different levels of receding background each with different heights within the scene. The road, although not visible in its entirety, is another convincing link between each area of action. An additional sense of reality is achieved by having a single light source, in this case from the top left corner of the picture, which provides matching areas of shadow in all the figures, buildings, and mountains. The use of perspective by artists like Mantegna was an important part of the early Renaissance movement where artists were now being recognised not only as mere craftsmen but also intellectuals capable of studying the past and using precise scientific and mathematical methods to achieve certain effects in their work.

Mantegna's reputation had by now gone beyond his adopted city and he moved to Verona in 1459 CE to create a painted altarpiece for the Church of Saint Zeno which includes an impressive treatment of the Crucifixion (now in the Louvre). The gilded frame of the altarpiece is avant-garde with its classical columns and pedestals. Mantegna was now a major Renaissance influence, and he applied his skills to various media throughout his career: paintings, frescoes, and copperplate engravings. His preferred subjects were mythology and religious scenes which are presented in his "brilliantly hard, linear style and bright non-atmospheric colour" (Hale, 199).

Palazzo Ducale Frescoes

Around 1460 CE, Mantegna was employed by the powerful Gonzaga family of Mantua to become their court artist. The head of the family at that time and the Marquis of Mantua was Ludovico Gonzaga (l. 1412-1478 CE), a man famed for his knowledge and support of the arts. Mantegna thus established in the city a large workshop with a number of assistants and apprentices. Amongst other works, Mantegna was commissioned to decorate the interior of the Castello di San Giorgio, a part of the impressive Gonzaga palace, the Palazzo Ducale. The work began in 1465 CE and took an unusually long nine years to complete.

Of particular note is the artist's treatment of the Camera degli Sposi ('bridal chamber' but known simply as the camera picta or 'painted chamber' at that time) which Ludovico used as his bedroom. The room is covered with imaginative frescoes inspired by episodes from his patron's life. Other members of the Gonzaga family also appear on the walls of the chamber, as do episodes from the lives of such heroes of Greek mythology as Hercules and Orpheus. The real wonder, though, is when one looks up. This was the first ceiling of the Renaissance period that created the illusion one is in a completely different kind of room than one actually is. There is the illusion of arched vaults with rich stucco work, and within each diamond space is a bust of a Roman emperor, each within a circle of laurel leaves. The oculus or opening in the very centre of the ceiling is spectacular and shows the sky and several naked cherubs dangling over the edge. In a joke that the observer is actually under observation themselves, various figures seemingly peer down into the room with one woman whispering into the ear of a man as if in commentary of what they can see below.

The dedication, written in carved Roman letters on a gold plaque above the room's doorway reads:

For the illustrious Ludovico, second Marchese of Mantua, best of princes and most unvanquished in faith, and for his illustrious wife Barbara, incomparable glory of womanhood, his Andrea Mantegna of Padua completed this slight work in the year 1474 CE.

(Paoletti, 356)

The finished room delighted all visitors and enhanced both the artist's reputation and Ludovico Gonzaga's as a ruler who was at the leading edge of artistic developments in Renaissance Italy.

Later Works

By 1488 CE Mantegna's fame had reached the ears of the Pope, and he was commissioned to produce frescoes in the Vatican's Chapel of the Belvedere. Unfortunately, these frescoes were later destroyed although the 'cartoon' sketches survive.

Back in Mantua by 1490 CE, Mantegna next produced his celebrated Triumph of Caesar, a series of nine tempera panels commissioned once again by the Gonzagas. The work, showing Julius Caesar's triumphant return to Rome after defeating the Gauls, was originally meant to be transferred into frescoes within a theatre in the Palazzo Ducale but the project was never realised. Today, these panels are in Hampton Court in London after they were bought by Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649 CE).

Towards the end of his career, Mantegna was trying ever more daring effects, most dramatically seen in the much foreshortened horizontal body of Christ in his Lamentation of Christ now in Milan's Pinacoteca di Brera. Other later works include the Madonna della Victoria which was made to commemorate the 1495 CE victory of Mantua (and allies) over French forces and which is now in the Louvre, Paris.

Finally, Mantegna famously produced two paintings for the private chambers of Isabella d'Este (1474-1539 CE), wife of Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga (1466-1519 CE), then ruler of Mantua. The two works are now in the Louvre, one is the Parnassus (1497 CE), the other is Virtue Triumphant over Vice (c. 1502 CE), and both are much busier compositions and more flamboyant than other Mantegna works.

The Virtue painting is packed full of imagery with Aphrodite/Venus shown keeping captive Virtue and standing near a loathsome swamp inhabited by eight vices (some of which are labelled): Sloth, Ingratitude, Ignorance, Avarice, Hate, Suspicion, Fraud, and Malice. There is, too, a dark figure standing in the pool carrying three labelled bags: 'the bad', 'the worse', and 'the worst', perhaps referencing the choice one has in choosing vice or virtue in one's actions. Athena/Minerva is assisted by Diana and Chastity, and she appears fully armed from the left, wearing a yellow robe. The trio are about to expel all of these vices from the olive grove. At the same time, three virtues (left to right: Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance or, alternatively, Faith, Hope, and Charity) await in the cloud above, ready to descend and complete the restoration of order, harmony, and beauty. The artist's love of classical architecture finds expression in the ordered arches which enclose this battle between good and evil. The whole work is entirely appropriate for the chambers of the leading lady of a court, who was imagined in those days as its guardian of moral values.

Legacy

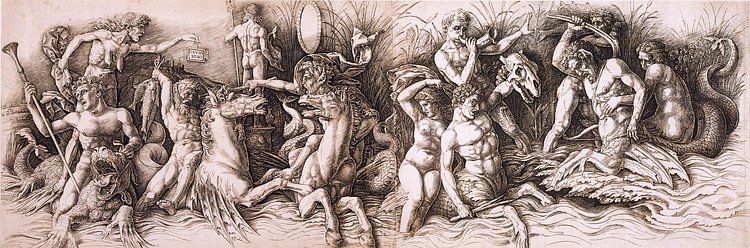

Mantegna was a brilliant draughtsman and this is seen best in his engravings where he seems to have used his carving tool as if it were his superbly controlled pen. The artist's attention to detail and technical execution in engravings helped make the genre a respected and popular one amongst collectors. One particular work was influential, his massive Battle of the Sea Gods engraving (c. 1490 CE), which Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE) took great interest in and transformed into a new work, his Bacchanal with Silenus (1494 CE).

In terms of painting, Mantegna's clever yet playful ceiling in the Palazzo Ducale would be imitated by such Renaissance artists as Raphael (1483-1520 CE) and Correggio (1489-1534 CE), and later painters of the Baroque style. Mantegna had also shown the way in his use of dramatic foreshortening, creating an effect of surprise on the viewer that artists would strive for ever after. Early and influential art historians such as Baldassare Castiglione (1478-1529 CE) noted that Mantegna was right up there with Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE), and Raphael (1483-1520 CE) as the very best of the Renaissance artists, a position he continues to enjoy today.