Andreas Karlstadt (also given as Carlstadt, l. 1486-1541) was a reformer, theologian, and early supporter of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) in the movement that became known as the Protestant Reformation. Karlstadt was one of Luther's most ardent advocates until 1522 when Luther denounced Karlstadt's innovations to liturgy in Wittenberg and villainized him.

Karlstadt, along with another of Luther's early supporters, Thomas Müntzer (l. c. 1489-1525), were publicly blamed by Luther for the German Peasants' War (1524-1525), during which the lower classes rose against the aristocracy and Church. It is likely Luther did this to deflect blame from himself as many felt his teachings had encouraged hostilities. Karlstadt defended himself against these charges but was associated with both Luther and Müntzer and, finding himself threatened, had to seek asylum at Luther's home, despite their differences.

Müntzer was killed in the war, and Karlstadt was prohibited by Luther from publishing. He supported himself as a merchant farmer before leaving Wittenberg for Switzerland in 1529 where he was welcomed by the reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) and, later, Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) and continued at his post in Basel until he died of the plague in December 1541. Although he has traditionally been referenced as a minor character in Luther's story, Karlstadt made significant contributions to the early years of the Reformation on his own and has steadily been recognized as an important voice in establishing the interpretation of Christianity which has come to be associated with the Reformed Church.

Education & Luther

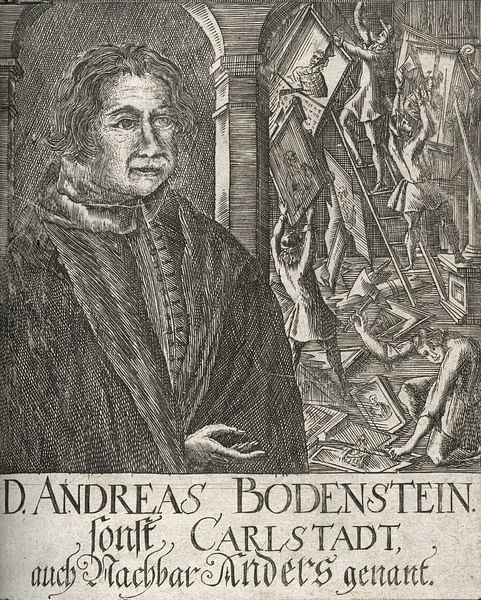

Karlstadt's actual name was Andreas Rudolph Bodenstein von Karlstadt as he was of the Bodenstein family of the city of Karlstadt. He was later referenced as Andreas Karlstadt (or Andreas Carlstadt) in correspondence, which is how he is best known. Nothing is known of his early life before Wittenberg except that he was well educated between 1499 and 1505 at the universities of Erfurt and Cologne. After arriving at Wittenberg, he received his doctorate in theology in 1510 and was appointed archdeacon of the Department of Theology.

Martin Luther arrived at Wittenberg at the suggestion of his mentor, Johann von Staupitz (l. c. 1460-1524), who recommended he take over Staupitz's chair of the Bible at the university. Karlstadt, as head of theology, awarded Luther his doctorate in 1512, and the two would afterwards discuss theological and philosophical issues. Karlstadt was regarded as the leading scholar at the university and was highly regarded as an intellectual while, at this time, Luther was unknown.

Karlstadt recognized his importance and frequently overstepped his authority, bringing him into conflict with his patron Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525), the elector and ruler of Saxony who contributed to the university and its faculty's income. Frederick III respected Karlstadt's position as the leading scholar at Wittenberg and, although their relationship was sometimes strained, allowed him to more or less do as he wished. In 1515, Karlstadt left for Rome to study for his law degree, remaining there for over a year on a leave of absence Frederick III had only agreed to for four months. When he returned, he was remarkably well-dressed and had developed a taste for expensive high fashion, which forced him to ask Frederick III for the pay of clerics who had recently died to maintain his wardrobe. This may have placed further strain on their relationship and could have contributed to later problems between the two.

His time in Rome and Siena was not all spent on outfitting himself, however, as he was a serious scholar who had applied himself to his law degree. He had also observed the excess of the Church of Rome firsthand (as Luther had done), and upon his return, he wrote up 151 theses for discussion with other clerics on possibilities for reform. Luther, meanwhile, had been moving away from Orthodox teachings himself and discussed his arguments against the Church policy of scholastic theology with Karlstadt in early 1517. Karlstadt cautioned Luther against heresy and consulted the works of Saint Augustine of Hippo (l. 354-430) in order to refute Luther's points. Instead, he found that Luther was right in rejecting scholasticism, which was based on reason, not faith, and began to question his own relationship with the Church.

Whereas he had previously cautioned Luther against criticizing the Church, he now spoke out against scholastic theology himself, and some scholars, including Lyndal Roper, claim he directly influenced Luther's 97 Theses on the subject. The 97 Theses were published in September 1517, a month before Martin Luther's 95 Theses were posted on the church door at Wittenberg. By this time, Karlstadt was already arguing against Church policy regarding the veneration of the saints and the place of icons in churches, but at first, he did not support Luther's objections to indulgences.

Leipzig & Worms

Luther's 95 Theses challenged the sale of indulgences – writs purchased to lessen one's time, or that of a loved one, in purgatory – and Karlstadt recognized that, without the sale of these writs, the financial stability of the Wittenberg church (and many others) would be jeopardized. His own income, also, would suffer, which would mean, among other sacrifices, he would have to abandon his fine wardrobe. At the same time, he understood Luther was right and there was no biblical basis for indulgences or for purgatory, for that matter, leading him to renounce his attachments to worldly goods and embrace the concept Luther advocated of faith alone and scripture alone as the means to communion with God and a fulfilling life.

Karlstadt began preaching the Reformed message in 1518 at the same time Luther's 95 Theses were published and widely distributed. Pope Leo X sent a series of delegates to try to silence Luther and Karlstadt, and among them was Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543), a Catholic theologian and former friend of Luther's, who wanted to debate Karlstadt at a meeting called at Leipzig in 1519. Luther, originally, was to play a secondary role, but Karlstadt's appearance at Leipzig is generally overlooked by historians because Luther took center stage and argued more eloquently. When the papal bull threatening Luther with excommunication was issued in 1520, Karlstadt was shocked to find himself named in it as Luther had clearly been more outspoken and controversial.

Karlstadt then moved further away from the teaching of the Church, and even from Luther's vision, toward a renunciation of worldly things in order to attain, "a state of mystical receptivity and openness where the boundaries between oneself and God disappear – as if one were to return to the womb where there is no separation between mother and child" (Roper, 211-212). Luther rejected this view, claiming that God had made the world for humans to enjoy, and a rejection of earthly pleasures was an ungracious repudiation of God's gifts. This difference in their views would cause their first division which would only grow larger.

Luther was excommunicated in January 1521, along with Karlstadt, and was ordered to appear at the Diet of Worms, an assembly called by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in an effort to unite his territories against a possible invasion by the Ottoman Empire. Since Luther's works had caused religious divisions, he was expected to explain himself and, hopefully, recant which would restore the unity Charles V needed. Luther did no such thing, however, and Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms in April 1521 elevated him to the status of a Christ-like figure among his supporters who now looked to him to finish what he had begun, overturn the institutions of the medieval Church and nobility, and usher in a new age of equality and prosperity for all, regardless of social standing.

Wartburg & Wittenberg

To the Catholic authorities and nobles, however, Luther was a dangerous threat and Charles V branded him an outlaw, meaning anyone could kill him without consequences. On his way back to Wittenberg, however, Luther was taken into protective custody by Frederick III and brought to Wartburg Castle. Karlstadt, meanwhile, was advancing the Reformation in Wittenberg. He preached against icons and in support of Luther's vision, and by the end of the year, he was offering communion 'in both kinds' meaning the laity were given both bread and wine, whereas according to Church policy, they were only to receive bread as the wine was reserved for the clergy. Roper comments:

Whereas earlier he had avoided preaching, now Karlstadt preached frequently and with passion. People remarked that he had become a new man, "such exquisite things did he now preach". When it became clear that [Frederick III] would be hostile to any "innovations", Karlstadt ignored him and, on Christmas Day, he invited those present who wished to take communion to do so, whether or not they had made confession. A thousand people are reported to have attended. To the horror of the [authorities], many of those who took communion had not kept the obligatory fast but had eaten and drunk beforehand; some were even said to have consumed brandy. Dressed in lay clothing, Karlstadt officiated at Mass in the parish church and, when the wafers were twice dropped – one falling on a man's coat, another onto the floor – he simply told the parishioners to pick them up. (212)

Having rid himself of his own elaborate trappings, he did the same with the liturgy and policies of the Church, calling for the removal of icons and delivering the Mass in German instead of Latin, dressed in street clothes like any of his parishioners. At Wartburg, Luther was constantly writing, sending out letters of encouragement to his fellow reformers, especially his right-hand man Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) but, pointedly, not to Karlstadt, who was primarily engaged in the efforts Luther had inspired and who had even written a prayer of praise in his honor. The day after Christmas, 1521, Karlstadt married the 15-year-old girl Anna von Mochau in defiance of Church policy prohibiting clerical marriage, at a ceremony attended by Melanchthon and others, with congratulations sent (later) from Luther. A few weeks later, Luther sent more letters encouraging people to support Karlstadt's efforts in Wittenberg in establishing a true Christian city based on biblical principles.

Karlstadt & Müntzer

The people of Wittenberg, especially the peasant class, needed no encouragement in dismantling the social hierarchy, and on 10 January 1522, most likely inspired by Karlstadt's friend and fellow reformer, Gabriel Zwilling (l. c. 1487-1558), a mob stripped the church of its icons and burned them. Roper describes the scene:

[The mob] made a fire in the cloister square, went into the church, broke the wooden altars, and took them with all the paintings and statues, crucifixes, flags, candles, chandeliers, etc. to the fire, threw them in and burnt them, and cut off the heads of the stone statues of Christ, Mary, and other saints and destroyed all the images in the church. (214)

Karlstadt not only approved but encouraged further iconoclasm elsewhere noting that the first commandment prohibited idol worship and defining church iconography as idolatry. While Karlstadt was advancing the cause in Wittenberg, Thomas Müntzer was doing the same elsewhere while also rejecting Luther as a hypocrite who had betrayed reform. Müntzer was in Wittenberg before Luther posted his 95 Theses and was an early supporter and part of Luther's inner circle with Karlstadt, Melanchthon, and others. He supported Luther and Karlstadt at Leipzig in 1519 and was rewarded by Luther with a position preaching in Zwickau.

While there, Müntzer associated with the mystic Nikolaus Storch (d. c. 1536) and his colleagues, the Zwickau Prophets, who denied Luther's claim that one needed only one's faith and the Bible; the prophets claimed God could communicate with believers in any way He saw fit, including dreams and visions, and the Bible was only one means of communion with the divine. Müntzer was already entertaining similar beliefs, and when Luther was rescued by Frederick III (instead of being martyred as it seems Müntzer thought he would be), he broke from the Lutheran vision and went his own way, denouncing Luther as a puppet of the nobility.

Luther's Return & Karlstadt's Exile

Duke Georg, cousin of Frederick III and a devout Catholic, appealed to Charles V to stop the spread of violence and destruction encouraged by the reformers, and on 20 January 1522, an imperial mandate was issued condemning the Reformation and giving Catholic authorities permission to punish the activists. Frederick III understood he would be implicated in the movement if he allowed it to continue on its present trajectory, and Luther also was aware of the threat to his patron. He contacted Frederick III saying he would return to Wittenberg and stop the violence, although he must have known this also meant withdrawing his support for Karlstadt.

Luther understood the political manipulations at work and how Duke Georg was waiting for an opportunity to remove his cousin and take his lands, and so he told Frederick III not to protect him or acknowledge their relationship. Up until this time, as Roper notes, "Luther appeared to have been very satisfied with how the Reformation was proceeding in Wittenberg" (221). Now, however, upon his return, he preached eight sermons against the uprising, iconoclasm, and, essentially, everything Karlstadt and Zwilling had been advocating for.

Zwilling apologized for his participation in the riots, was forgiven, and sent quietly away to a pastor's position in Altenburg, but Karlstadt remained in Wittenberg, ostracized by Luther who now associated him subtly, and not so subtly, with the devil and blamed him for encouraging rebellion against civil authorities. Karlstadt was now also rejected by those he had led and was turned away by the university when he tried to publish his most recent works. When he received an invitation to preach in Orlamunde, he accepted and left Wittenberg.

At Orlamunde, Karlstadt completely broke with Luther and continued the same course, now condemned by Luther as 'radical', that he had followed when Luther was at Wartburg and which the latter had earlier encouraged, including the removal and destruction of icons in churches. Now, though, he rejected Luther's interpretation of the Eucharist as embodying Christ and moved toward Zwingli's view of the ritual as a memorial of Christ's sacrifice in which God was spiritually, not physically, present. He also adopted the Anabaptist rejection of infant baptism, claiming an infant could not make a conscious decision to accept Christ. Luther rejected both of these concepts and labeled Karlstadt a heretic.

Luther continued his attack on Karlstadt in letters and by prohibiting him from publishing anything, anywhere, without his approval. In August 1524, Karlstadt met Luther in the city of Jena at the Black Bear Inn where Luther accused Karlstadt of radical leanings and of being in league with Müntzer, who, by this time, was associated with the social unrest that was spreading throughout southern Germany. Karlstadt defended himself, noting how he had written to Müntzer at Allstedt, his base of operations, refusing to support him in armed resistance and rejecting any alliance between Orlamunde and Allstedt. Luther dismissed Karlstadt's explanations and defense and left the meeting after, essentially, telling his former friend to do his best to try to write anything against him and see what good came of it. A month later, Karlstadt was banished from Saxony by Frederick III, who had no further use for him since he had become Luther's patron.

Conclusion

The frustration of the lower classes over their treatment by the nobility and the Church, and their disappointment that the 'new teachings' had done nothing to alleviate their suffering, finally culminated in the German Peasants' War that broke out shortly after Karlstadt was exiled. Luther preached against the uprising just as he had against the disturbances in Wittenberg, causing Müntzer to attack him further for betraying the common people and supporting the status quo. Müntzer led a contingent of peasants in the war, while Karlstadt, threatened by people who associated him with Luther or with Luther's attacks on him, returned secretly to Wittenberg. With nowhere else to go, he was forced to ask Luther for sanctuary and was taken in along with his family in return for signing a retraction of any negative remarks he had made about Luther.

Müntzer was executed after the Battle of Frankenhausen in May 1525, ending the war, and Luther, who had been attacked by peasants while on a speaking tour that year, published his Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, advocating for their execution. There is no record of Karlstadt's reaction to this pamphlet because Luther still prohibited him from preaching, teaching, or publishing, and he supported himself and his family as a farmer and merchant until 1529 when he left for Switzerland, preaching in Zürich and associating first with Zwingli and later with Bullinger. By 1534, he was in Basel where he remained the dean of the University of Basel until he died of the plague in December 1541.

Although Luther is rightly recognized for his pivotal role in launching the Protestant Reformation, Andreas Karlstadt was the first activist in Wittenberg to challenge the authority of the Church. He both inspired and was inspired by Luther, at first cautioning and then encouraging him to take the stand he is famous for. Like Müntzer and, to a lesser degree, Melanchthon – as well as others who supported Luther's early efforts – Karlstadt was rejected by Luther when it seemed expedient to do so and continues to be referenced mainly as a footnote to Luther's story. He was instrumental in establishing the Reformation in his own right, however, and recent scholarship is working to elevate him to the stature and recognition he should have received long ago.