The Anglo-Nepalese War (aka Gurkha War, 1814-16) saw the British East India Company (EIC) lose several battles against Nepalese Gurkhas before finally securing victory in a hard-fought campaign that, for the first time, extended EIC control beyond the borders of India. Impressed with the Gurkhas' fighting abilities, the British have enrolled them in their armies ever since.

East India Company Expansion

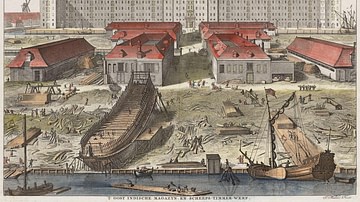

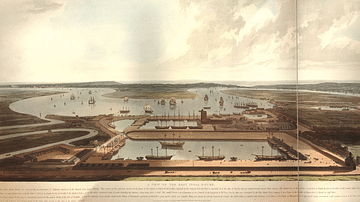

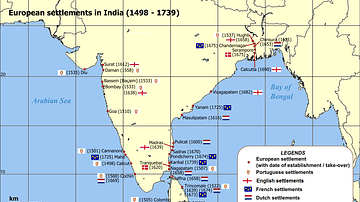

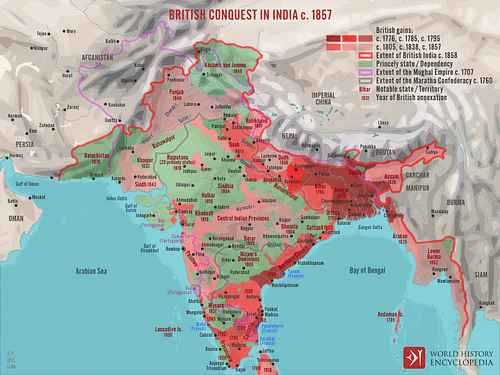

The East India Company was founded in 1600, and by the mid-18th century, it was benefiting from its trade monopoly in India to make its shareholders immensely rich. The Company was effectively the colonial arm of the British government in India, but it protected its interests using its own private army and hired troops from the regular British army. By the 1750s, the Company was keen to expand its trade network and begin a more active territorial control in the subcontinent.

Robert Clive (1725-1774) won a famous victory for the EIC against the ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah (b. 1733) at the Battle of Plassey in June 1757. The Nawab was replaced by a puppet ruler, the state's massive treasury was confiscated, and the systematic exploitation of Bengal's resources and people began. The EIC won another key contest in October 1764 with victory at the Battle of Buxar (aka Bhaksar) against the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II (r. 1760-1806). The emperor then awarded the EIC the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a major development and ensured the Company now had vast resources to expand and protect its traders, bases, armies, and ships.

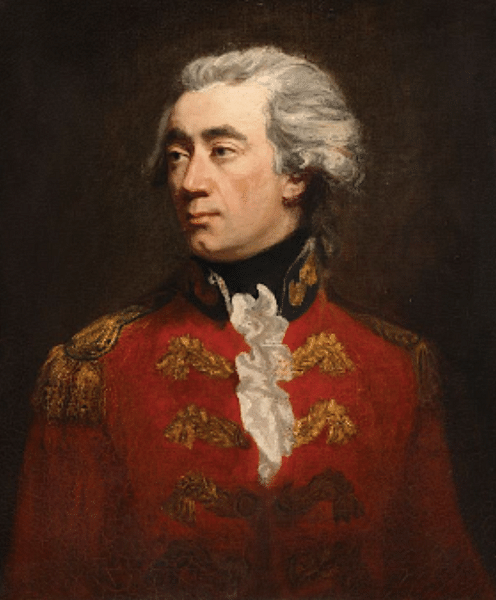

The EIC kept on expanding through diplomacy and military conquest. Victories came against the southern kingdom of Mysore across the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799). Intertwined with these conflicts were the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819) against the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India. Once again the EIC came out as the winner. The Company had extended its control of the subcontinent not only through direct territorial possessions but also through a policy of Subsidiary Alliances, where rulers of the Indian princely states were obliged to have an EIC resident at their court, host and pay for an EIC garrison, and hand over the direction of foreign policy to the British. With large parts of India now in its grasp, the ever-avaricious East India Company and its new Governor-General the Marquess of Hastings (in office 1813-23) began to look to the far north for further opportunities for profit. Consequently, the next EIC target was Nepal, and it declared war on the kingdom in April 1814.

Gurkha Victories

The Himalayan kingdom of Nepal, with its capital at Kathmandu and fierce fighting men the Gurkhas (aka Gorkhas), had long been in dispute with its neighbours. The Nawab of Bengal had tried to limit the Gurkha expansion in 1762 but had been roundly defeated at the Battle of Makwanpur. The Gurkhas then completed their domination of the Nepal Valley, and by 1768, Kathmandu ruled over various subjugated hill chiefs in the region.

The Nepalese were particularly keen to enlarge into the southern border region, which was then controlled by the state of Awadh (aka Oudh), a protectorate of the EIC since it had signed a treaty of Subsidiary Alliance in 1801. The Nepalese and British, therefore, shared a border some 700 miles long (1125 km). Into the 19th century, the Gurkha raids into their southern neighbour's territory were relentless. A small EIC force sent to better garrison the area was wiped out in April 1814. Governor-General Hastings believed that only a large-scale military action would settle the issue, and he noted: "To be foiled by the Gurkhas, or so make a discreditable accommodation with them, would have led to incalculable mischief" (James, 65). Not for the first time, the British convinced themselves that a colonial pacification of a region would only, in the end, bring it greater prosperity. Accordingly, Hastings sent four separate armies into Nepal, but three of these columns were repeatedly defeated in several hard-fought encounters.

The Gurkha army, whose commander-in-chief was Amar Singh Thapa (1751-1816), only numbered between five and eight thousand men during the war, but crucially, they were fighting on familiar home territory. One notable EIC loss was at the Battle of Jitgurh (aka Jit Gadhi), where the EIC army was led by General Wood. The victorious Gurkha commander was Ujir Singh Thapa (1852-1881). A notable casualty early in the war was Major General Gillespie, who had commanded another EIC force that failed to take the hill fort of Jaitak near Dehra in October-November 1814. The terrain made it difficult for EIC armies to transport their artillery and give the general logistical support armies in the field needed. One siege, for example, had to be abandoned merely for lack of ammunition for the cannons. The forts the Gurkhas retreated within were also very tough to attack, given that many were perched on hilltops, which made assault by artillery and infantry difficult.

Above all, the Gurkhas were tough-fighting men. Their famous weapon was the kukri knife with a long and curved, machete-like blade which was used as a slashing weapon, a tool to cut one's way through forest, and a means to clinically mutilate the enemy dead, something the Gurkhas became infamous for. The Nepalese were also armed with matchlock firearms. Gurkha tactics involved guerrilla warfare, which best exploited the difficult rugged mountain and forest terrain. They avoided open battles or large offensive operations, which meant the EIC could rarely use its cavalry. The impractical combination of cannons and hilltop forts is, significantly, shown in the medal the EIC issued participants in the Anglo-Nepalese War. The Gurkhas also had the advantage that they could forage and fish for food, and they could easily return to their mountain villages between encounters, whereas the British logistics were severely tested so far from their bases in Bengal. The British were further hampered by Gurkhas poisoning certain water sources, a tactic noticed when several elephants and horses used by the EIC as transport died unexpectedly. Ultimately, Hastings was obliged to send bigger and better-led armies to the frontier in a new round of fighting in 1815.

Ochterlony & Victory

The most successful EIC commander in Nepal was Sir David Ochterlony (1758-1825), known for his meticulous planning and conservative approach to warfare. He learnt from the mistakes he and his fellow commanders had made in the early stages of the war and began to reverse the trend of EIC losses. Ochterlony besieged the major Gurkha fort of Malaon and captured Kumaun (Kumaon) in May 1815.

The EIC attempted to negotiate a peace settlement, but the Nepalese were not willing to give up territories or their independence and so decided to fight on. The interim lull in hostilities allowed the Nepalese to heavily fortify all three passes to the Valley of Nepal. The EIC, not for the first time in its wars, used subterfuge to get the better of an enemy. Employing local smugglers as guides, an EIC army of 15,000 men, the largest yet employed in the conflict, made its way through the hills, bypassing the usual fortified passes.

On 28 February 1816, at the Battle of Makwanpur, Ochterlony orchestrated the most decisive EIC victory in Nepal. More battles and sieges followed with Ochterlony taking the time to build roads to get his heavy cannons into better positions to blast the Gurkha forts. The Gurkhas were a constant threat to the EIC's supply lines, but their overall strategy, which favoured defensive actions over offensive ones, meant that the enemy took the initiative. Eventually, with Kathmandu under direct threat from Ochterlony and faced with the relentless campaigning by the EIC with its far superior resources which meant it could continuously replenish losses in material and men, the Nepalese decided to sue for peace.

Aftermath

Under the terms of the 1816 Treaty of Sugauli, the Nepalese rulers were obliged to have a permanent British resident at their court, withdraw from Sikkim, and give up a large swathe of their territory to the EIC – this included the kingdoms of Kumaun and Garhwal. In effect, Nepal became a British protectorate but at least, unlike many Indian princely states, they did not have to pay an annual subsidy to the EIC. Unlike countless other such treaties, this one lasted, and there were no further hostilities between Nepal and the EIC.

After the Nepalese war, the EIC next moved on to the northeast to fight the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-85) and to the northwest and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49). The Gurkhas, meanwhile, became valuable allies to the East India Company with, for example, Gurkha battalions participating in the Sikh Wars and playing an important part in the Company quashing the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8. The military historian R. Beaumont states that the Gurkhas became "the most famous mercenaries of Asia" (29). By 1914, one-sixth of the Indian Army was made up of Gurkhas. Such was the prestige and reputation for loyalty of the Gurkhas, they were the first non-British soldiers to be given the honour of guarding Buckingham Palace, the London residence of the British royal family. Gurkhas still serve today in the Nepalese, British, Indian, and Malaysian armies.