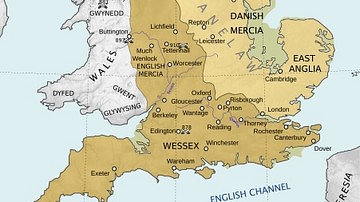

Anglo-Saxon warfare was characterised by frequent and violent conflicts between petty kings, which ultimately led to the rise of larger kingdoms such as the Kingdom of Mercia, the Kingdom of Northumbria, and the Kingdom of Wessex. In early Anglo-Saxon England, military success was expected of a king: conquering lands and collecting tribute was how a royal warlord rewarded his followers and ensured their loyalty.

Sources

We are provided with several primary sources on Anglo-Saxon warfare. For descriptions of military campaigns, we have the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by the 8th-century Northumbrian monk Bede, and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a chronicle recorded at the royal court of the West Saxon dynasty. Poems, including Beowulf, the Battle of Brunanburh, and the Battle of Maldon, provide insight into military culture, with Beowulf explaining that the Danish king, Scyld Scefing, was a good king precisely because he had beaten his neighbouring tribes into submission and received tribute from them.

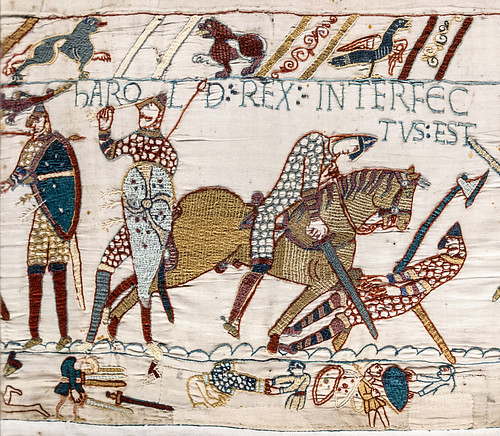

Archaeological findings and the Bayeux Tapestry provide visual representations of warriors and their weaponry and finally, law codes, land charters, and the Domesday Book help explain military customs, including landowners' military obligations and the expected number of soldiers each region could muster.

Weapons & Equipment

A wealthy warrior in Anglo-Saxon England would typically be equipped with a spear, a round shield, a mail shirt, and a conical helmet. At his waist hung a sword belt, which carried a sword and a seax – a short, knife-like blade. Expensive items like swords and helmets were markers of wealth and status. Swords were often family heirlooms; Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) notably bequeathed a sword to his son-in-law in his will. Among the most famous archaeological finds of the era is the Sutton Hoo helmet, thought to belong to an East Anglian king. Assembled from iron and bronze, the helmet's intricate design marks it as a great work of craftsmanship, exemplifying its owner's prestige and royal status.

While horses were prominent in the culture of the early Anglo-Saxon settlers – their two legendary founders were named after horses, Hengist (Stallion) and Horsa (Horse) – there is little evidence of their use in battle. There are two primary references to horses being used in warfare, though neither points to common usage. The first reference comes in the Battle of Brunanburh poem – recounting the great battle of 937. After defeating the rival alliance of Scots and Vikings, the English warriors chased their retreating foes and cut them down while on horseback. The second reference comes in a 1055 passage of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, describing Edward the Confessor's (r. 1042-1066) Norman nephew, Ralph the Timid, leading a cavalry unit into battle against the Welsh. However, Ralph's army retreated before the fighting began due to their unfamiliarity with fighting on horseback. Fighting, thus, remained chiefly the domain of infantry soldiers, and while the Brunanburh poem suggests horses could be used in post-battle attacks, their purpose in warfare was primarily transportation, allowing armies to move with greater mobility.

Ships played a limited role in early Anglo-Saxon warfare despite the seafaring origins of the first Anglo-Saxon leaders. The first hint of any kingdom projecting sea power is 7th-century Northumbria, which conquered the Isle of Man and Anglesey and raided Ireland. However, the first recorded Anglo-Saxon naval battle was not until 851, when King Aethelstan of Kent (r. 839-851) fought a Viking fleet off the coast of Sandwich. Aethelstan's younger brother, Alfred the Great, further developed naval power, fighting the Vikings at sea several times and designing his own fleet. However, his naval operations were limited to intercepting small raiding parties rather than fighting large Viking fleets. Yet for Alfred's heirs, naval power was a key asset; Alfred's son, Edward the Elder (r. 899-924), had a fleet of 100 ships, and his successors used ships to attack Scotland, Normandy, and the Isle of Man. Edward's grandson, Edgar the Peaceful (r. 959-975), was also credited with establishing an administrative system for manning his ships, known as the 'ship-soke' system, whereby each region of the kingdom was required to send a set number of sailors to serve in the king's navy.

Tactics & Battle

Military campaigns in Anglo-Saxon England were often brief affairs and typically based on a single decisive battle. Both sides often engaged in negotiations before battle. For instance, before the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the English king, Harold Godwinson (r. 1066), sent an envoy to William the Conqueror, demanding he leave England. According to William of Poitiers – a contemporary Norman priest – William replied by offering a legal trial to determine who had the superior claim to the English crown or, alternatively, a duel in single combat. Harold refused both offers.

Military leaders also often sought divine support before battle. For example, before the Battle of Ashdown in 871, King Aethelred I of Wessex (r. 865-871) attended mass in his tent. In the moments before battle, the commander would rally and encourage his troops, as shown in the Battle of Maldon poem, which describes a battle with Viking raiders in 991:

Then Brihtnoth [Ealdorman of Essex] began to array his men; he rode and gave counsel and taught his warriors how they should stand and keep their ground, bade them hold their shields aright, firm with their hands and fear not at all.

(Whitelock, 317)

Archery was uncommon amongst the English, but missile exchanges usually occurred at the beginning of a battle, with both sides hurling javelins at each other. The primary battlefield tactic used by the Anglo-Saxons was the shield wall – as portrayed on the Bayeux Tapestry – where soldiers formed a straight line, standing shoulder to shoulder, holding their shields in front of them, to create a protective barrier. While often a defensive tactic, this formation could also serve as an offensive strategy, allowing armies, with their shields locked, to charge at their opponent as a single unit. After exchanging missiles, each side would march toward the other, and the shield walls would collide. This would often become a contest of shoving and thrusting, with each side aiming to drive the other backwards. If one shield wall was longer than the other, it could attempt to overlap or surround the smaller one, seeking to attack it from multiple angles. Once in contact, spears were a key weapon in the shield wall and could be thrust from overhead or from the waist to kill or wound front-line enemies. Killing your opposing number could create a gap in the opponent's shield wall, which, when broken, would often result in chaotic hand-to-hand combat.

Turning points in battle often came with the capture of an enemy banner or the death of a leader, which would crush the morale of his followers. At Hastings, Harold's death led his army to flee or surrender, as was the case with most of Brihtnoth's army at Maldon. However, those few warriors in the personal service of a military leader were expected to stay and fight for their lord after his death so that they might avenge him or die in their attempt. As the Maldon poet explains, after Brihtnoth's companions witnessed his death, they continued to fight "to lose their lives or avenge the one they loved" (Whitelock, 319).

Social Hierarchy & Military Organisation

The king sat at the pinnacle of the social hierarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. His duties included leading the kingdom's army, defending its borders, overseeing royal councils, and enacting just laws. Beneath him were his ealdormen, great lords typically responsible for supervising a province or shire of the kingdom. Below them were the thegns, an aristocratic class of landowning warriors and officials. Next came the ceorls or freemen, who comprised most of the population. They generally worked the land as farmers, though the term 'ceorl' included individuals whose economic status and freedom varied considerably. At the bottom of the social ladder were the slaves, whose enslavement often resulted from capture in war or punishment for crimes. A man's status in this social hierarchy was measured by his wergild, or 'man price': the sum paid to his family in the event of his murder, paid for by the killer. For example, a Northumbrian law code, The Law of the North People, decreed that the wergild for an ealdorman was 8,000 thrymas (gold coins), while a thegn's wergild was only a quarter of that, at 2,000 thrymsa.

Richard Abels explains the military system of early Anglo-Saxon England as consisting of the king's retinue and the followers of his landed nobles (32). Young men of noble birth, called geoguth ('youths') in Old English poetry, began their adult lives serving in the household of the king or a great lord. They formed the personal retinue of their master, protected him in battle, accompanied him as he travelled throughout the kingdom, and lived under his roof. Those who proved courage in battle and loyalty to the king were rewarded with estates of their own, thus marking their elevation in status from a geoguth to a duguth ('tried man'). They would thereafter lead their own household and command their own young warriors, comprised of sons of nobles and perhaps those from the upper ceorlish families residing on their new lands. However, a ceorl could also be assigned non-combat roles, including carrying food supplies and extra weapons. A gift of land from the king bound its recipient in loyalty to him; the new landowner was now expected to raise troops to support the king in battle and attend his councils. This land, however, was 'loanland': returning to the crown upon the death of the duguth.

During the 8th century, royal land grants increasingly became hereditary, resulting in a more fixed hierarchy as noblemen could pass on their wealth to their sons. During the reigns of the Mercian kings Aethelbald (r. 716-757) and Offa (r. 757-796), specific royal duties known as the 'three common burdens' were introduced as conditions of land ownership. These included military service and maintaining local bridges and fortresses. While the landowner, be he an ealdorman or thegn, would lead his troops into battle, his followers would generally be expected to undertake bridge and fortress work. Eventually, these practices were extended into Mercia's neighbouring kingdoms of Kent and Wessex.

The military obligation of a landowner to his king came from both their oaths of loyalty and land ownership. However, the extent of their service was proportionate to the size/value of their land holdings. According to the Domesday Book, typically, one soldier was summoned for military service from every five hides of land – a hide was a unit of land measurement equal to the amount needed to support one household. Five hides were the standard required land value for its owner to acquire the status of a thegn; thus, they would form a large share of the army. Yet, thegns who owned more than five hides would be expected to raise additional warriors; for example, a thegn possessing 50 hides would be obligated to raise ten warriors. Thegns would organise and lead their warbands to regional mustering points, where the army of a shire or province would gather and then be led to support the king by the ealdorman of the region.

The Reforms of Alfred the Great

This Anglo-Saxon military system of the early 9th century was designed for warfare between the English kingdoms or against the Welsh. However, it proved ill-suited for countering Viking raids in Britain, whose mobility, via ships and horses, allowed them to plunder or capture towns, often before facing significant opposition. Once a town was captured and barricaded, they could strike nearby settlements from these strongholds or defeat English leaders who unsuccessfully tried to besiege them. The failure of Anglo-Saxon defences led to devastating consequences and from 867 to 874, three kingdoms, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria, fell entirely or partially under Viking control.

The one king who survived long enough to address the inadequacies of English defences was the West Saxon ruler, Alfred the Great, who, after winning the Battle of Edington in 878, gained the breathing space to make sweeping military reforms. Alfred's most significant innovation was creating the burghal system, which entailed the construction of 30 burhs – fortresses or fortified towns – across Wessex. These burhs were protected by timber ramparts, defensive ditches, and a garrison of soldiers supplied by local landowners. They were connected by a network of roads, allowing one garrison to aid a nearby burh when under attack, and they were each within 20 miles (32 km, about one day's march) of all Alfred's subjects, allowing them to seek refuge during Viking invasions.

Alfred also reformed his army. The main issue was speed or the lack thereof. Beyond his household warriors, Alfred had no standing army. When attacked, Alfred would have to order his nobles to raise their armies, which would gather locally before marching to his aid. This was time-consuming, and maintaining these large armies was difficult because their warriors were reluctant to spend extended periods away from their homesteads. To solve this, Alfred divided his armies into two rotating divisions: one half would be a standing army, ready for deployment at any moment, while the other would remain at home, overseeing local estates and acting as a regional police force. The standing armies were also equipped with horses, ensuring rapid response to Viking attacks.

These reforms were largely successful and led to several victories over Viking leaders, embellishing Alfred's reputation among his nobles and fellow rulers and strengthening his kingdom. These military practices were extended to Mercia, ruled by Alfred's son-in-law, Aethelred, Lord of the Mercians (r. 883-911), and used by Alfred's children – Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, and Edward the Elder – and by his grandsons to conquer the East Midlands, East Anglia and Northumbria. Thus, by 927, Edward's eldest son, King Aethelstan (r. 924-939), became the first ruler of a united English kingdom.

By the 960s, the Viking threat had subsided, ushering in a golden age of peace and prosperity. The burdens of landowners had eased, and many of Alfred's burhs transitioned from military strongholds to commercial hubs with eroding defences. However, a second Viking Age began during the reign of Aethelred the Unready (r. 978-1016), for which England was wholly unprepared. Aided by factionalism, ineffective leadership, and a failure to rejuvenate the military system, the Vikings returned to power in England in 1013, as Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark overthrew Aethelred. However, it was Sweyn's son, King Cnut the Great (r. 1016-1035), who completed the Danish conquest of England, ruling competent for two decades before the West Saxon dynasty was restored in 1042 under Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066).

Peace-making

Peace in Anglo-Saxon England was not merely the cessation of hostilities but something actively negotiated. It often transformed relationships between rulers from rivalry to friendship, secured through dynastic marriages, tribute payments, or oaths of friendship. While peace could be established on equal terms, it more often resulted from one leader recognising the supremacy of another.

Kings who enjoyed supremacy, such as Penda (r. 626-655) and Offa of Mercia, might expect tribute and military support from subordinate rulers in exchange for protection, peace, and friendship. Both Penda and Offa also married their female relatives to lesser kings to strengthen these relationships. Yet, when rulers in conflict were more evenly matched, the medieval Church – a trusted mediator by both sides – often acted as a peace-maker. This was the case during the 7th-century wars between the Mercians and the Northumbrians. Despite Northumbria's efforts at peace through marriage and tribute, it was only Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury's intervention in 679 that ended the long-lasting conflict.

Pagan Vikings were unbound by Christian and Anglo-Saxon customs, and Alfred the Great failed to negotiate peace with tribute and hostage exchanges with them. Only after demonstrating his military supremacy, with a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington in 878, could he impose peace on the Vikings. Alfred also insisted upon the conversion of the Viking leader Guthrum, believing that only a fellow Christian king could be trusted to keep the peace. Their peace treaty established a defined border and trade regulations between their kingdoms, and their new friendship was symbolised by Alfred standing as Guthrum's godfather, along with 12 days of feasting and an exchange of gifts.

This model of peace with Viking leaders – based on baptism and friendship – was continued by Alfred's successors. In 926, his grandson, Aethelstan, secured peace with his chief rival, King Sihtric of York (r. 921-927), who agreed to baptism and marriage to Aethelstan's sister, transforming their relationship from rivals to Christian brothers. Another grandson, Edmund I (r. 939-946), stood as godfather at the baptism of King Olaf II of York (941-944 & 949-952) in 943 as part of their peace treaty. However, these treaties remained subject to the lifespan and opportunism of their makers. Aethelstan, for example, conquered York upon Sihtric's death in 927 and Edmund chased Olaf, his godson, into exile in 944.

Long-term peace was only achieved when kings could unify England and maintain a loyal following and vast resources to defend it. Most notably, this occurred during the reign of the aptly named 10th-century king, Edgar the Peaceful, who reduced his neighbouring Celtic kings to subordination, allowed the recently annexed Kingdom of York to follow its old laws, and was known for his harsh punishments of those who disturbed the peace.