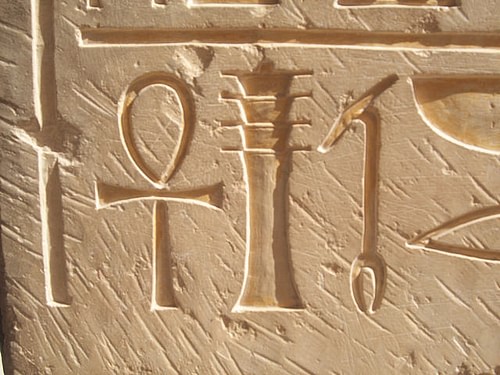

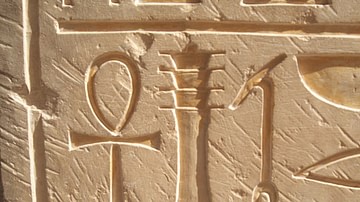

The Ankh is one of the most recognizable symbols from ancient Egypt, known as "the key of life" or "cross of life" and dated to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - 2613 BCE). It is a cross with a loop at the top sometimes ornamented with symbols or decorative flourishes but usually just a plain gold cross.

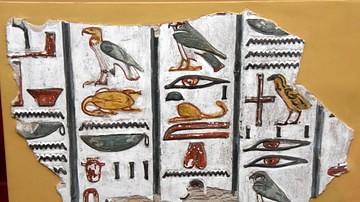

It is an Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol for "life" or "breath of life" (`nh = ankh) and, as the Egyptians believed that one's earthly journey was only part of an eternal life, the ankh symbolizes both mortal existence and the afterlife. It is one of the oldest symbols of ancient Egypt, often seen with the djed and was symbols, carried by a multitude of the Egyptian gods in tomb paintings and inscriptions and worn by Egyptians as an amulet.

The ankh's association with the afterlife made it an especially potent symbol for the Coptic Christians of Egypt in the 4th century CE who took it as their own. This use of the ankh as a symbol of Christ's promise of everlasting life through belief in his sacrifice and resurrection is most probably the origin of the Christian use of the cross as a symbol of faith today.

The early Christians of Rome and elsewhere used the fertility symbol of the fish as a sign of their faith. They would not have considered using the image of the cross, a well-known form of execution, any more than someone today would choose to wear an amulet of an electric chair. The ankh cross, already established as a symbol of life, lent itself easily to assimilation into the early Christian faith and continued as that religion's symbol.

Origin & Meaning

The origin of the ankh is unknown. The Egyptologist Sir Alan H. Gardiner (1879 - 1963) thought it developed from a sandal strap with the top loop going around one's ankle and the vertical post attached to a sole at the toes. Gardiner came to his conclusion because the Egyptian word for "sandal" was "nkh" which came from the same root as "ankh" and, further, because the sandal was a part of one's daily life in ancient Egypt and the ankh sign came to symbolize life. This theory has never gained wide acceptance, however.

The theory of Egyptologist E.A. Wallis Budge (1857-1934), who claims it originated from the belt buckle of the goddess Isis, is considered more probable but still not universally accepted. Wallis Budge equated the ankh with the Egyptian symbol tjet, the "knot of Isis", a ceremonial girdle thought to represent female genitalia and symbolizing fertility. This theory, of the ankh's origin stemming from a fertility symbol, is in keeping with its meaning throughout ancient Egyptian history and beyond to the present day. Egyptologist Wolfhart Westendorf (b. 1924) supports Wallis Budge's claim noting the similarity of the ankh to the tjet and the use of both symbols from an early date in Egypt's history. The ankh has always been associated with life, the promise of eternal life, the sun, fertility, and light. Scholar Adele Nozedar writes:

The volume of meaning that can be squeezed from such a simple symbol is awe-inspiring. The ankh represents the male and female genitalia, the sun coming over the horizon, and the union of heaven and earth. This association with the sun means that the ankh is traditionally drawn in gold - the color of the sun - and never in silver, which relates to the moon. Putting aside the complexities of these separate elements, though, what does the ankh look like? Its resemblance to a key gives a clue to another meaning of this magical symbol. The Egyptians believed that the afterlife was as meaningful as the present one and the ankh provided the key to the gates of death and what lay beyond. (18)

It is for this reason that ankh figures so prominently in tomb paintings and inscriptions. Deities such as Anubis or Isis are often seen placing the ankh against the lips of the soul in the afterlife to revitalize it and open that soul to a life after death. The goddess Ma'at is frequently depicted holding an ankh in each hand and the god Osiris grasps the ankh in a number of tomb paintings. The association of the ankh with the afterlife and the gods made it a prominent symbol on caskets, for amulets placed in the tomb, and on sarcophagi.

The Ankh & the Goddess Isis

The ankh came into popular usage in Egypt during the Early Dynastic Period with the rise of the cults of Isis and Osiris. The association of the ankh with the tjet mentioned earlier is supported by early images of Isis with the tjet girdle prior to the appearance of the ankh.

The cult of Osiris became the most popular in Egypt until the cult of Isis - which told the same story and promised the same rewards - dominated it. Osiris continued to be greatly admired but, in time, became a secondary character in the story of his resurrection and rebirth. At the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, however, it was the cult of Osiris that was dominant as he was the god who had died and returned to life, thus bringing life to others. Isis, at this time, was a mother goddess associated with fertility but was soon joined to Osiris as his devoted wife who rescued him after his murder by Set and returned him to life. Egyptologist Flinders Petrie writes:

Isis became attached at a very early time to the Osiris worship and appears in later myths as the sister and wife of Osiris. But she always remained on a very different plane to Osiris. Her worship and priesthood were far more popular than those of Osiris, persons were named after her much more often than after Osiris, and she appears far more usually in the activities of life. Her union in the Osiris myth by no means blotted out her independent position and importance as a deity, though it gave her a far more widespread devotion. The union of Horus with the myth, and the establishment of Isis as the mother goddess, was the main mode of her importance in later times. Isis as the nursing mother is seldom shown until the twenty-sixth dynasty; then the type continually became more popular until it outgrew all other religions of the country. (13)

Many of the gods of Egypt are depicted holding the ankh but Isis more often than most. In time, Isis became the most popular goddess in Egypt and all the other gods were seen as mere aspects of this most powerful and all-encompassing deity. The cult of Isis promised eternal life through personal resurrection. In the same way that Isis had rescued her husband Osiris from death, so could she rescue those who placed their faith in her. The association of the ankh with such a powerful goddess imbued it with greater meaning in that now it was linked specifically with the great goddess who could save one's soul and provide for one in the afterlife.

The History of the Ankh in Use

The importance of the ankh lay in the instant recognition of what the symbol stood for. Even those who could not read would have been able to understand the symbolism of objects such as the djed or the ankh. The Egyptian ankh was never solely associated with Isis - as mentioned, many gods are depicted carrying the symbol - but as the djed became linked to Osiris, the ankh fell more into the realm of Isis and her cult.

By the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 - 2181 BCE) the ankh was well-established as a powerful symbol of eternal life. The dead were referred to as ankhu (having life/living) and caskets and sarcophogi, ornamented regularly with the symbol, were known as neb-ankh (possessing life). During the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) the word nkh was used for mirrors and a number of hand-mirrors were created in the shape of the ankh, the most famous being that found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The association of the ankh with the mirror was no chance occurrence. The Egyptians believed that the afterlife was a mirror image of life on earth and mirrors were thought to contain magical properties. During the Festival of the Lanterns for the goddess Neith (another deity seen with the ankh) all of ancient Egypt would burn oil lamps through the night to reflect the stars of the sky and create a mirror image of the heavens on earth. This was done to help part the veil between the living and the dead so one could speak to those friends and loved ones who had passed on to paradise in the Field of Reeds. Mirrors were often used for divination purposes from the Middle Kingdom onwards.

The ankh was also a popular amulet which was worn in life and carried to the grave. Scholar Margaret Bunson writes:

Called wedjau, the amulets were made out of metal, wood, faience, terracotta, or stone and believed to contain magical powers, providing the wearer with supernatural benefits and charms. The potential power of the amulet was determined by the material, color, shape, or spell of origin. Living Egyptians wore amulets as pendants and the deceased had amulets placed in their linen wrappings in their coffins. Various styles of amulets were employed at different times and for different purposes. Some were carved as sacred symbols in order to attract the attention of a particular deity, thus ensuring the god's intercession and intervention on behalf of the wearer. (21)

The djed was a very popular amulet but so was the ankh. Although the most common amulet in ancient Egypt was the sacred scarab (the beetle), the ankh was almost as widely used. During the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE), when the cult of the god Amun was increasing in power and stature, the ankh became associated with him. The ankh was used in temple ceremonies regularly at this time and became associated with the cult of Amun and royalty.

During the Amarna Period (1353 - 1336 BCE), when Akhenaten banned the cult of Amun along with the rest of the gods and raised the god Aten as the sole deity of Egypt, the ankh sign continued in popular use. The symbol is seen in paintings and inscriptions at the end of the beams of light emanating from the solar disc of Aten, bringing life to those who believe. After Akhenaten's death, his son Tutankhaten (whose name contains the ankh symbol and means "living image of the god Aten") took the throne, reigning 1336-1327 BCE, changed his name to Tutankhamun ("living image of the god Amun") and reinstated the old religion, retaining the ankh with the same meaning it had always held.

The ankh remained a popular symbol even though Akhenaten's reign was despised and Tutankhamun's successor Horemheb (1320 - 1292 BCE) tried his best to erase all evidence of the Amarna Period from Egyptian culture and history. The greatest ruler of the New Kingdom, Ramesses II (r. 1279 - 1213 BCE) employed the ankh regularly in his inscriptions and it continued in use throughout the remainder of Egypt's history.

The Ankh & Christianity

As Christianity gained more widespread acceptance in the 4th century CE many of the symbols of the old religion fell into disfavor and were banned or simply forgotten about. The djed symbol, so closely associated with Osiris, was one of these, but the ankh cross continued in use. Scholar Jack Tresidder writes of the ankh:

Its shape has been variously understood as the rising sun on the horizon, as the union of male and female, or other opposites, and also as a key to esoteric knowledge and to the afterworld of the spirit. The Coptic church of Egypt inherited the ankh as a form of the Christian cross, symbolizing eternal life through Christ. (35)

While other vestiges of the old religion slipped away, the ankh took on a new role while retaining its old meaning of life and the promise of eternal life. Adele Nozedar comments:

Powerful symbols frequently stray across into other cultures despite their origins and the ankh is no exception. Because it symbolizes immortality and the universe it was initially borrowed by the fourth-century Coptic Christians who used it as a symbol to reinforce Christ's message that there is life after death. (18)

The ankh cross as a symbol of eternal life eventually lost its loop at the top to become the Christian cross which, like the ancient ankh, is worn by believers in Jesus Christ in the present day for the same reason: to identify with their god and all that god promises.