Anne of Austria (1601-1666), as the wife of King Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643), was queen consort of France and of Navarre when the Kingdom of Navarre was annexed by the French Crown. She also acted as regent for her son, King Louis XIV of France (1638-1715), during the early years of his reign.

Early Life

Anne was born in Valladolid, Spain, on 22 September 1601 to King Philip III of Spain (r. 1598-1621) and Margaret of Austria (l. 1584-1611). Her childhood was spent at the Royal Alcazar in Madrid, Spain. Growing up, Anne was constantly visiting monasteries and would soon follow in her parents' footsteps and become very religious. In 1611, Anne's mother died in childbirth, and so the responsibility of raising her younger siblings was passed down to Anne.

While a Spaniard, Anne had Austrian ancestry and was considered an Austrian Archduchess as well as a Princess of Spain and Portugal, which is why she is referred to as ‘of Austria'. Anne was described to be a very beautiful girl, even at a young age, with fair hair that could often be found in large curls, greenish-blue eyes, and an oval face. Her beauty and political position would help Anne gain the attention of many suitors.

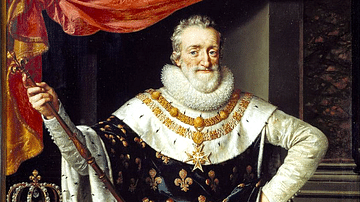

The most successful of Anne's suitors was none other than King Louis XIII of France (l. 1601-1643), and when their betrothal was announced to the people of Paris on 18 March 1612, there were celebrations throughout the city. There were balls, banquets, and celebratory parties being hosted in the Louvre (the residence of French royalty), Fontainebleau Palace, and St. Germain. This was a political marriage, and Anne's father thought this would be a good chance to bring France into the Habsburg world; the couple married in 1615 when Anne was 14 years old.

As it would turn out, the union between Anne and Louis was very cold. Louis prioritized activities common for young men of high status, such as hunting rabbits in the garden of the Tuileries Palace, and would allow himself to fully listen and be governed by his favorite advisors in court; as such, he had almost no relationship with Anne.

Queen Consort of France

Anne's life as queen consort was filled with trials and tribulations; French court life was not peaceful, and her transition to living in France was not a smooth one. Anne arrived in France with her Spanish ladies-in-waiting, and they were really the only people she interacted with. Since she did not expand her circle and mainly followed the Spanish customs she was comfortable with, she was not able to get a fluent grasp of the French language, and as a result, she was perceived and ridiculed as the "Foreign Queen." Charles d'Albert (1578-1621), the Duke of Luynes and one of the king's advisors, saw the cold relationship between Louis and Anne and took the initiative to assimilate Anne with French culture. First, he sent away all of the Spanish ladies-in-waiting and replaced them with French women. He then began to dictate how she would dress and behave so she could leave behind any Spanish mannerisms.

Although the duke's actions helped to bring Anne and Louis together, Anne's reputation throughout the court was tarnished due to her several miscarriages and stillbirths. Louis was especially angry when Anne miscarried after she fell while running with two friends in 1622. It was not until more than 15 years later that Anne was finally able to give birth to two sons: the future King Louis XIV and Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (1640-1701).

One of Anne's greatest adversaries in court was Armand Jean du Plessis or Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642), Louis' Chief Minister and most trusted advisor after the death of the Duke of Luynes. Richelieu was a firm believer that a monarchy was the most natural form of government, and he saw Habsburg dominance in Europe as a threat to the power of the French king. France was surrounded by Habsburg territories while also facing internal challenges, so instead of engaging in direct conflict, Richelieu built alliances with other states in an attempt to diminish Habsburg power. In his quest to make France a global power, Richelieu also began to build a navy. Through his efforts, by 1635, French naval power surpassed that of the English and was on par with the Spanish.

Richelieu's attempt to increase the authority of the French Crown was often at the expense of Huguenots, the French Protestants, especially in La Rochelle, a Protestant stronghold of the French Reformation. The Siege of La Rochelle (1627-1628) ended Huguenot political power and signaled a shift to a stronger monarchy. Despite the tensions between the French government and the Huguenots, Richelieu created alliances with Protestant states during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) in order to weaken the Catholic Habsburgs, and thereby build French authority.

While Richelieu held immense power and the king's favor, Anne, as a Habsburg, was neglected, isolated, and distrusted in court. In an effort to keep an eye on her, Richelieu sent Madeline du Fargis to spy on Anne as a lady in her circle. His plan, however, backfired as the two became close friends. In 1630, Anne plotted with her mother-in-law, Marie de' Medici (1575-1642), to get Louis to dismiss Richelieu from the French court but their plan failed; Richelieu remained, and Louis never truly trusted Anne again after this event. As punishment, Louis reduced the number of ladies Anne had in her circle to half of what she had originally and removed du Fargis, her favorite.

There were also rumors that Anne was working with Henri de Talleyrand-Périgord, Comte de Chalais (1599-1626) to overthrow Richelieu when, in 1632, letters were found from du Fargis to different people in Paris, which described plans to marry Anne to Louis' younger brother Gaston, after Louis' death. When questioned, Anne denied knowing anything about the content of the letters. Chalais was executed, and although Anne remained unharmed, the affair did nothing to improve her relationship with Louis or Richelieu.

Anne spent a lot of time at the convent of Val de Grace, so Richelieu placed a monk in the sisterhood in hopes that he would be able to relay any information about Anne's correspondence with her Spanish relatives, France's enemy. It was discovered that Anne always left and picked up her letters at the convent of Val de Grace. In 1637, when he had enough evidence, Richelieu decided to reveal that she was communicating with her brother, Philip IV of Spain (r. 1621-1665). France had been at war with Spain for two years and so she was committing treason. During questioning, Anne initially denied all accusations, but she eventually gave in. From this point forward, everything she wrote had to be inspected by Richelieu, she was no longer to visit convents without permission, and she was always surrounded by those who were loyal to Louis or Richelieu.

Queen Regent

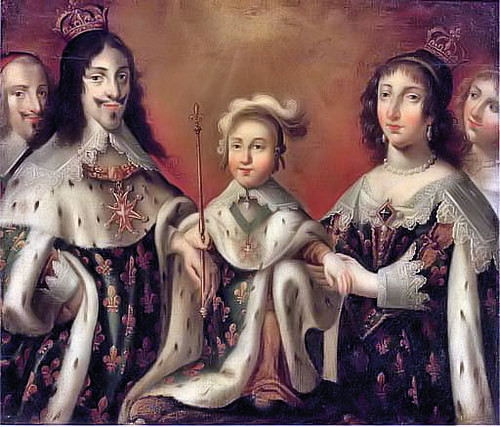

After many years of misfortune, Anne finally carried a pregnancy to full term, and on 5 September 1638, Louis XIV was born. It was regarded as a miracle, and France rejoiced at the birth of an heir. It was even more surprising when 15 months later, Anne conceived another child. On 21 September 1640, Philippe I was born. Even though Anne had finally given him children, Louis still treated Anne with a cold demeanor because of her past actions, Anne, so she spent much of her time with her sons.

On 14 May 1643, Louis XIII died of tuberculosis. In his final will, Louis included a provision that would prevent Anne from becoming the regent for Louis XIV, but Anne was able to convince the Parlement of Paris to annul the will. Anne was aware that she did not have the skills to run France on her own, so she made Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino or Jules Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661) her Chief Minister. Surprisingly, Anne did not just undo everything the late Richelieu and her husband had done, but rather, she continued their policies, including the war against Spain, and focused on securing her son's rights and his throne.

One of the biggest threats that Anne faced as queen regent was the Fronde, a series of civil wars and aristocratic rebellions in France from 1648 to 1653. In order to strengthen the monarchy, Richelieu had ordered the destruction of the castles or fortresses of the nobles who were participating in the planning of a revolt or of those who failed to provide the expected loyalty and services to the kingdom. Richelieu had also convinced the king to introduce a harsh punishment for dueling. The punishment included loss of public function and pension and possibly a three-year banishment. If someone were to perish in the duel or ask for others to join in, then there would be a death penalty. During his administration, Richelieu had even upset the judiciary; many of the regional parlements complained of the reduction and retention of pay and circumventing the way the courts reviewed the law. In essence, Richelieu's policies had stripped the nobles of their privileges, relegated them back to their specific realms, and placed them further under the authority of the king. The reaction to these policies revealed themselves during the regency of Anne.

The first half, the Fronde of the Parlement, saw the nobles demanding to put a limit on the power of the monarchy; after much violence, the French government established the Peace of Rueil (1649), which temporarily ended the conflict but left France in a state of fragile peace. During the second half, the Fronde of the Princes, the Mazarinade pamphlets were published criticizing both Mazarin and Anne. The pamphlets criticized Anne's governance and the way she was raising her sons and began to discuss how she was corrupted by Mazarin through some supernatural force and was therefore corrupting the government. There were rumors that she loved Mazarin more than her own children, and some speculated that the two may have married. After many battles, several of the nobles being exiled, attempts to permanently remove Mazarin, and the Parlements having no control over the crown, the Fronde was over, and Anne and Mazarin were victorious in 1653.

Although Anne's regency ended in 1651 when Louis XIV was announced of age to rule, Anne continued to work with her son and Mazarin. With Louis XIV's power consolidated, Anne took the initiative to get back into contact with her Spanish relatives. After retiring from politics, Anne moved to the convent of Val de Grace, where she remained until she died of breast cancer in 1666.