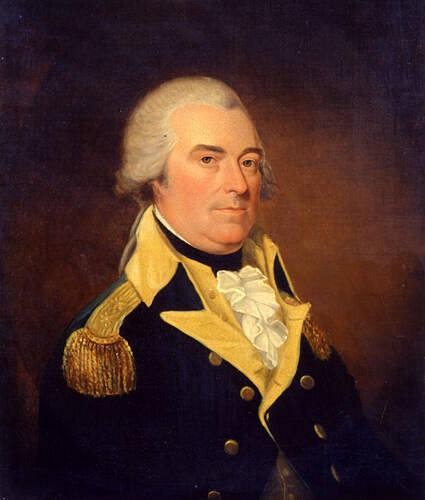

Anthony Wayne (1745-1796), better known by his nickname 'Mad Anthony', was a brigadier general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). After the war, he briefly served in Congress before resuming his military career, winning a victory over a coalition of Native American nations at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

Born in Pennsylvania to a family of Irish immigrants, Wayne worked as a land surveyor before joining the Continental Army in 1776. Within a year, he had become a brigadier general, serving with distinction in the Philadelphia Campaign. His finest moment came in July 1779, when he led a nighttime raid against the British garrison at Stony Point, New York, capturing the fort even after sustaining a bullet wound to the head. After the American Revolution, Wayne won election to the House of Representatives as a member of the Federalist Party, working to help strengthen the authority of the federal government. In 1792, he became Senior Army Officer and defeated the Northwestern Confederacy of Native American nations that were contesting the United States' control of the Northwest Territory (modern Ohio). Wayne died shortly after his victory at Fallen Timbers on 15 December 1796, at the age of 51.

Early Life

Anthony Wayne was born on 1 January 1745 at his family's estate of Waynesborough in Easttown, Pennsylvania. He came from a family of Irish Protestants, and his grandfather had fought for the Williamites at the Battle of the Boyne (1 July 1690). In the early 1700s, the Wayne family emigrated from Ireland to the British colony of Pennsylvania, where Anthony's father, Isaac Wayne, found work as a tanner; over the decades, his tannery became the largest in Pennsylvania. In 1739, at the age of 40, Isaac Wayne married Elizabeth Iddings. The couple would have four children, of whom Anthony was the eldest. During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Isaac served as a captain and raised a company of provincial soldiers. He participated in the 1758 Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, in which he served alongside a young Colonel George Washington.

Growing up, Anthony Wayne was expected to inherit the 500-acre Waynesborough and work the fields as a farmer. But Wayne had other plans for his future; having listened to heroic tales of his grandfather's and father's military service as a child, the young Anthony dreamt of winning military glory himself. An insatiable reader, Wayne read all the military histories and classical works he could get his hands on and was soon able to recite both Julius Caesar and William Shakespeare. After completing his education at the College of Pennsylvania, Wayne became a land surveyor. In 1765, he and several of his associates were commissioned by Benjamin Franklin to survey 100,000 acres of land in Nova Scotia. After Wayne surveyed the land, which became the township of Monckton, it was settled by eleven Pennsylvania families of mostly German origin.

In 1763, Wayne married Mary Penrose. The couple had two children: a daughter Margarette (b. 1770) and a son, Isaac (b. 1772). Wayne and his growing family continued to live at Waynesborough, where he split his time between helping his father at the tannery and his own work as a surveyor. But, as relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain continued to deteriorate, Wayne found that he was being drawn toward the Patriot movement, which opposed the 'unjust' policies of the British Parliament such as taxation without colonial representation. In 1775, a year after the death of his father, Wayne was nominated to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, a shadow government run by American revolutionaries; on this committee, he served alongside prominent Patriot leaders like Benjamin Franklin and John Dickinson.

In this position, Wayne became increasingly radical in his disdain for the British, leading his primarily Quaker constituents to remove him from the committee in October, for fear that he had become too war hawkish. By now, the American Revolutionary War was underway and rapidly escalating. With his brief foray into politics over, Wayne could now follow his childhood dream and enter the military.

In the Continental Army

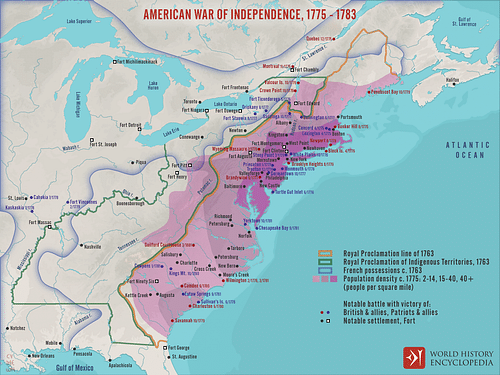

On 3 January 1776, Wayne received a commission as a colonel in the 4th Pennsylvania Line Regiment of the newly formed Continental Army. After a few months of training, the regiment was sent north to bolster the Patriot forces in the failing American invasion of Quebec; Wayne had his first combat experience on 8 June 1776 at the Battle of Trois-Rivières, the last action of the Revolutionary War fought on Canadian soil. After the failure of the expedition, the Patriot troops withdrew to Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. Command fell to Wayne, who was quickly faced with several major problems: the soldiers, having just tasted defeat, were ill-disciplined and mutinous, the supply line to Ticonderoga was stretched dangerously thin, and the threat of a British attack loomed heavy on the horizon. Wayne proved adept at handling these difficulties, however, and saw the garrison of Ticonderoga through the winter. In recognition of his leadership, he was promoted to brigadier general in February 1777 and reassigned to the main army under General Washington.

In the spring, Wayne arrived at Washington's headquarters at Morristown, New Jersey, just as the army was preparing for that year's campaign season. Washington's main opponent, British General Sir William Howe, was headquartered in British-occupied New York City, where he had long been plotting a strike against the United States' capital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a killing blow to the American rebellion. In late July 1777, Howe made his move, loading an army of 16,000 men onto ships and setting sail for Chesapeake Bay. Washington was initially unsure of Howe's destination; it was not until August, when the British ships were spotted off the coast of Maryland, that he realized the capital was in jeopardy. The 14,000 troops of the main Continental Army raced into Pennsylvania, taking up a defensive position between the capital and the British at Brandywine Creek, not far from Wayne's home. The war had come to his backyard, and Wayne was determined to fight.

On the Homefront

At the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777), Wayne played an important role. For hours, his division defended the center of the American line at the crossing point of Chadds Ford against an onslaught of Hessian soldiers. It was only after the British outflanked and overwhelmed the American right flank that Wayne's defense crumbled, and the Hessians broke through; during the subsequent retreat, Wayne was forced to abandon his cannons to the enemy. After the defeat, Washington began a withdrawal toward the Schuylkill River but ordered Wayne to stay behind with 1,500 men. Wayne's task was to remain behind the British lines and harass their rear in order to slow Howe's advance toward Philadelphia. But unbeknownst to Wayne, the British had learned of his presence behind their lines almost immediately.

On the night of 20-21 September, a British detachment under General Charles Grey snuck up on Wayne's sleeping troops, encamped at Paoli Tavern. To maintain the element of surprise, Grey ordered his men to remove the flints from their muskets and attack only using the bayonet. The British surprise attack succeeded, as Grey's troops ran through the camp, skewering the Americans as they stepped groggily from their tents. Wayne and the other survivors managed to escape into the dark Pennsylvanian woods, leaving as many as 300 American soldiers dead, wounded, or captured. The Battle of Paoli, or massacre as the Americans called it, stained Wayne's reputation, as he was widely blamed for not anticipating such an attack. Although he was cleared of any wrongdoing by a board of inquiry, Wayne was never quite able to shake off the humiliation of Paoli.

Several days later, Wayne's reputation suffered further. During the American offensive at the Battle of Germantown (4 October), his division became lost in thick fog. With vision obscured, his men became the victims of friendly fire from another American unit that mistook them for British; in the ensuing panic, Wayne's division retreated, opening up a gap in the American line that the British quickly exploited. The defeat at Germantown, compounded by the recent British capture of Philadelphia, disheartened the Continental Army as it moved into winter quarters at Valley Forge. Exposed to the elements and lacking adequate clothing and food, around 2,000 Continental soldiers would die that winter. It was not until Washington installed Nathanael Greene as the army's new quartermaster general that the supply situation began to improve; Greene sent Wayne and other generals out across the countryside on foraging expeditions that turned up enough food to guarantee the army's survival through the winter.

'Mad' Anthony

By June 1778, the Kingdom of France had entered the war on the American side, forcing the British army to consolidate their position by abandoning Philadelphia and retreating to Manhattan. Washington was not about to let the British Army retreat unscathed and pursued the redcoats as they retreated through New Jersey. On 28 June, Wayne's division made up part of the vanguard of the Continental Army, under the command of General Charles Lee. Believing the British detachment camped near Monmouth Court House to be smaller than it really was, Lee sent his vanguard to attack; however, poor planning and communication on Lee's part led the assault to quickly break down, and the Continentals were soon in full retreat. The situation was only salvaged by the arrival of Washington and the main army, which fought the British to a draw in the subsequent Battle of Monmouth.

After Monmouth, the war in the north settled into a stalemate; Washington's army took up residence in New Jersey to keep an eye on the British army concentrated in Manhattan. There were, however, sporadic British outposts along the Hudson River in New York State that Washington hoped to capture so that he could wrest control of that vital waterway from enemy hands. The British cliffside fortress at Stony Point, which commanded access to the southern part of the Hudson, was of particular interest to Washington; plans for its capture were put into the hands of Wayne, who spent weeks meticulously planning a raid.

Finally, on the night of 16 July 1779, Wayne put his plans into action and assaulted Stony Point with 1,500 light infantrymen; taking a page from General Grey's playbook, Wayne ordered his men to only use the bayonet. At first, the British put up stiff resistance, firing a volley into the oncoming Continentals that took down 17 of the 20 men in the initial group of attackers. Wayne himself took a bullet to the head, but the wound only momentarily stunned him, and he was soon back on his feet bellowing commands. Within 30 minutes, the Americans had captured the fort; 15 Americans had been killed and 83 wounded, as well as 20 British killed and around 550 taken prisoner. The Battle of Stony Point, regarded as Wayne's finest moment, redeemed him for his loss at Paoli in the eyes of his contemporaries.

In 1780, Wayne continued to carry out operations in the lower Hudson Valley; he notably skirmished with a party of Loyalists at Bull's Ferry on 20-21 July and took command of the Patriot stronghold of West Point in September, after the exposure of Benedict Arnold's treason. In January 1781, Wayne was instrumental in the suppression of the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny, dismissing nearly half the regiment. That summer, he was sent south to Virginia to counter a British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis. On 6 July 1781, Wayne's 900 men fell into a trap at the Battle of Green Spring, when they found themselves surrounded by nearly 7,000 British troops. Rather than surrender, Wayne ordered a frenzied bayonet charge and broke out of the encirclement; it is believed that it was from this reckless, yet successful, action that he earned his nickname 'Mad' Anthony. He went on to participate in the Siege of Yorktown, where he was wounded in the leg. On 19 October 1781, Wayne witnessed the surrender of Cornwallis to Washington, signaling an end to the active phase of the war.

Planter & Politician

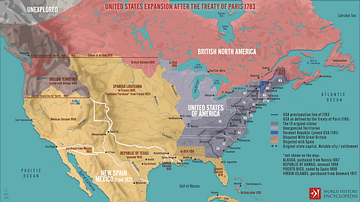

After Yorktown, Wayne was sent south, to deal with Britain's Indigenous allies who were still hostile to the Americans. In June 1782, he defeated the Creeks in Georgia and negotiated treaties with both the Creek and Cherokee people. In September 1783, as peace was finalized with the Treaty of Paris, Wayne received a promotion to major general and resigned from the army two months later. In 1786, the state government of Georgia gifted him several plantations that had been confiscated from Loyalists, and he moved to the South to begin his new life as a planter. Although Wayne had previously written to express his disgust with the way some slaves had been treated in Continental Army camps, he nevertheless purchased several enslaved people to work on his new plantations and even hired an overseer to direct their labor.

As the United States continued to struggle under the Articles of Confederation, Wayne became a strong believer in a more powerful central government. He supported Georgia's ratification of the United States Constitution, and in 1790, he won election to the House of Representatives in Georgia's 1st congressional district. During Wayne's two years in Congress, he supported the Federalist Party and championed a stronger national military to defend against future incursions by the British. In 1792, Wayne's campaign manager was accused of election fraud, sparking a special election for Wayne's congressional seat; sensing his own unpopularity, Wayne decided not to run again. He returned to his Georgia plantations only for his wife to leave him, due to the many extramarital affairs that the womanizing Wayne had committed. To make matters worse for the former general, his inexperience as a planter led him to fall quickly into debt.

Fallen Timbers

As Wayne was experiencing these political and personal failures, the United States was undergoing a crisis on its western borders. In the so-called Northwest Territory in modern-day Ohio, several Native American nations joined together in a loose coalition, known as the Northwestern Confederacy, to slow the encroachment of US settlers onto their lands. In 1791, the United States sent an expedition under General Arthur St. Clair to assert its claim to the region. But, at the Battle of the Wabash (4 November 1791), St. Clair's army was wiped out by the Native American coalition, marking the most complete defeat ever inflicted on a United States military force. In 1792, President Washington called Wayne out of retirement and asked him to lead a second military expedition against the Northwestern Confederacy.

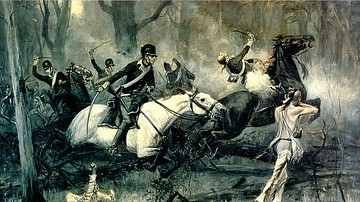

Wayne accepted the request and was named Senior Army Officer of the Legion of the United States, as the small US Army was then called. Working closely with Secretary of War Henry Knox, Wayne carefully trained his men and, in December 1793, constructed Fort Recovery in Ohio. The fort was the site of several skirmishes in the spring, but all assaults made by the Indigenous warriors (backed by Canadian settlers) were repulsed. In the summer of 1794, Wayne led an offensive into the Northwest Territory that culminated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794). At the battle, months of training and drilling paid off, as Wayne's men won a decisive victory over the Northwestern Confederacy and their Canadian allies. After the battle, the triumphant Wayne embarked on a scorched earth campaign against the Indigenous peoples, burning their villages and food stores. This led to the Treaty of Greenville the following year, in which the Native Americans were forced to renounce their claims to lands in the Northwest Territory. The victory also compelled the British, who had maintained forts in the area in violation of the terms of the Treaty of Paris, to evacuate the region.

Death & Legacy

A year after the signing of the Treaty of Greenville, Wayne went to Detroit to inspect the military post there. On his way back to Pennsylvania, he fell ill and died on 15 December 1796. His cause of death is unknown; stomach ulcers and complications from gout have both been put forward as possible causes. At various points in history, it has even been speculated that Wayne had been poisoned by James Wilkinson, his second-in-command. Wilkinson felt slighted when Washington chose Wayne to command the Legion of the United States over him and actively sabotaged the army during the Fallen Timbers campaign. Wayne learned of the treachery of his second-in-command and was in the process of arranging Wilkinson's court martial when he died. However, no evidence has been found to corroborate the claim that Wilkinson did indeed poison Wayne.

In the centuries since his death, Wayne has had a controversial legacy. Some historians have praised his military accomplishments, considering him to be in the upper tier of American Revolutionary generals. Others have derided his aggression that often bordered on recklessness, as well as his womanizing. Wayne's legacy has also been tarnished by his status as an enslaver as well as his treatment of Native Americans during the Northwest Indian War. Nevertheless, he undoubtedly played a significant role in the military history of the United States and the development of the US Army.