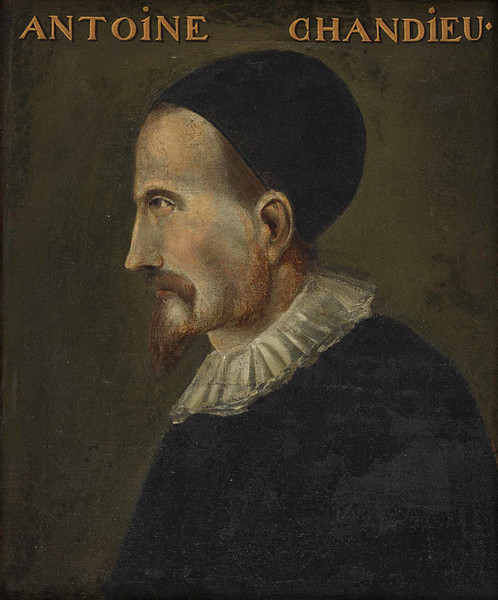

Antoine de Chandieu (l. 1534-1591) was a French theologian, who played a decisive role in the religious history of the 16th century but remains in the shadow of other French Protestant leaders. Due to his remarkable abilities and contribution to the Reformation in France, Chandieu has been considered the “Silver Horn” between the better-known John Calvin (Gold) and Theodore Beza (Bronze).

Early Years

Antoine de la Roche was born in Dauphiné, a former province in southeastern France, into an ancient family, the barons of Chandieu. He was known as Monsieur de la Roche until the death of his brother Bertrand at the Battle of Dreux in 1562 at which time Antoine became the sieur de Chandieu. His father died when he was four, and his widowed mother saw to the education of Antoine and his older brother Bertrand, heir of the name de Chandieu and the lordship of Chandieu. Antoine was directed toward formal studies in preparation for a government position, and his brother was destined for military service. Sent to Paris for his education, Antoine was placed in the care of a tutor influenced by the ideas of John Calvin (1509-1564) and continued his studies in Toulouse, a city marked by religious repression. Despite persecution by the Parlement of Toulouse, reputed as the bloodiest in all of France, the Protestant Reformation attracted secret followers and sympathizers. The conversion and martyrdom of several respected professors led students to leave their study of law for Geneva to study the Bible.

Pastoral Ministry

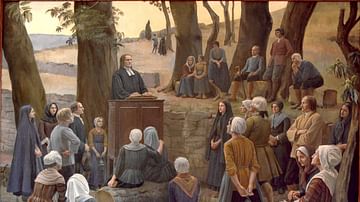

La Roche left Toulouse for Geneva and was won to the evangelical faith through Calvin's influence. He returned to Paris in 1555 where Reformed believers were organizing a church under the leadership of Jean le Maçon, known as La Rivière. Soon the church's responsibilities required another pastor, and La Roche became one of three pastors in the church. Protestants generally gathered at night in small groups in homes throughout different neighborhoods of the capital. In this way, the church was able to meet without arousing suspicion.

On 4 September 1557, 300-400 Reformed believers gathered to observe the Lord's Supper in a large home on the rue Saint-Jacques in proximity to the College du Plessis. Upon leaving at midnight, the attendees were pelted by stones amassed by the priests of the College du Plessis, who had been spying on the assemblies. The noise awakened the entire neighborhood and armed citizens blocked the passages of escape. Many inside decided to force their way through the crowd behind sword-bearing gentlemen. Others, mostly women, children, and old men, feared leaving and remained in the besieged house the rest of the night. Come morning, they were arrested and dragged through the enraged mob to the Châtelet and imprisoned. Most of them languished in the dungeons; seven were burned at the stake. Despite this event, the Protestant assemblies were not suspended, and the precautions were redoubled in the face of increasing danger. After the attack at rue Saint-Jacques, La Roche was arrested along with Jean Morel and Pastor de Lestre. La Roche and de Lestre were liberated while Morel remained imprisoned and wasted away subject to multiple torments for several months. In February 1559, his life ended in the misery of his dungeon with the suspicion of poisoning and his corpse burned as a heretic.

At the end of 1560, La Roche was sent by the church of Paris to the convocation of the Estates General at Orléans. The Protestant cause appeared lost. The trial of several ministers, including La Roche and La Rivière, was imminent, and the church consecrated the last ten days of November to prayer. The death of King Francis II of France on 5 December 1560, changed everything, and the Queen Mother, Catherine de' Medici (l. 1519-1589), reportedly requested the church of Paris to send La Roche to meet with her out of a desire to receive religious instruction. The Consistory sent a memorandum in his place, rather than put La Roche's life in danger. Reformed believers enjoyed a respite from persecution as Catherine sought to further weaken her opponents' influence.

Of all the pastors in Paris, La Roche was the best known and the most threatened due to his great abilities and his social status. For his protection, the Consistory of Paris occasionally required him to leave Paris when his adversaries were in pursuit. He refused an offer to leave France to join the refugees in London, and when ministry in Paris became impossible, he served other churches without remuneration.

Some historians have seen the hand of La Roche in the Confession of Faith and Discipline of Reformed churches in 1559 at the first national synod and his influence in subsequent synods. He was the author of the Épître au roi (Letter to the king) that was attached to the Confession of Faith and presented to Francis II after the failed Conspiracy of Amboise in 1560, a plot to kidnap the king and remove him from his advisors' influences. La Roche's brother Bertrand was implicated in the failed conspiracy, and La Roche, judged guilty by association, was rejected by the Queen Mother as a delegate to the Colloquy of Poissy in 1561, an unsuccessful attempt to avoid civil war and reconcile the Roman Catholics and Protestants of France.

Expulsion from Paris

A time of needed rest for La Roche at his estate in Beaujolais was interrupted by the massacre of Protestants at Vassy in March 1562 when a large congregation of Huguenots was attacked by soldiers of François, Duke of Guise. The incident sparked more slaughter and the beginning of the French Wars of Religion. The breakout of the first war of religion forced all Reformed pastors to leave Paris when Huguenots were expelled in May. Pastors, elders, and many other Protestants found refuge at Orléans, a bulwark of the Reformed army. With the city under siege and ravaged by plague, La Roche and his colleague La Rivière ministered for a year with an important influence on other ministers who had found refuge there.

In the name of Reformed churches, La Roche led the opposition during negotiations for the Peace of Amboise in 1563. The treaty ended the first war of religion and became a source of discouragement for Reformed believers with limitations on places of worship. In 1563, La Roche published his History of Persecutions and Martyrs of the Church in Paris from 1557 to the Time of King Charles IX, and he wrote in his journal that Reformed churches felt abandoned and in a worse state than before the war. The sixth article of the treaty forbade Reformed worship in Paris and effectively exiled La Roche and La Rivière from their Paris church.

Chandieu in Exile

At the death of his brother at the Battle of Dreux in December 1562, La Roche became the head of his family and was addressed as Monsieur de Chandieu. Neither his new title nor his fortune changed anything in his simple lifestyle; he remained committed to his pastoral calling. In 1563, he married Françoise de Felin of the family of the lords of Banthelu, a family devoted to the Reformed cause. Françoise remained Chandieu's faithful companion for 28 years.

A provincial synod meeting at La Ferté in 1564 with 38 ministers and 60 elders under the presidency of Chandieu demonstrated the vigor of reorganized Protestant churches in the Paris region, Picardy, and Brie. The fifth national synod met secretly in Paris in 1565, although it is not known if Chandieu was present. His care for the church of which he remained pastor was through letters, prayer, and stealthy visits. Finally, in June 1567, he received authorization from the Consistory to return to his ministry with prudence. Yet three months later, at the beginning of the second war of religion, he was forced to withdraw once again from Paris. He would never return to the capital.

Chandieu labored in Bourgogne to reorganize and establish churches in places authorized by the Peace of Amboise. He consecrated his time and strength to the church of Lyon, a large congregation that had remained in Protestant hands during the first war of religion. Of the three Protestant temples in Lyon built to replace those taken from them, one was demolished in 1566 before its completion, and the two others suffered the same fate the next year at the beginning of the second war of religion. Protestants were expelled from the city, their possessions were confiscated, and any remaining Protestants who refused to convert to Catholicism were imprisoned. Pastors were especially pursued and Geneva again received refugees who were cared for with funds from Protestant lands. The Peace of Longjumeau in March 1568 ending the second war of religion provided no relief with its unfulfilled promises. The king forbade Protestant worship in Lyon, and in flagrant violation of the edict's provisions, the religious prisoners were not released, and confiscated possessions were not returned to their owners.

Chandieu fled his home in August 1568 after several attempts on his life. He wandered for nine days with his antagonists in pursuit. He crossed the Saône River at midnight, made his way to Geneva, then ravaged by a plague, and went on to Lausanne before returning to Geneva. One month after his flight, Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574) forbade the practice of the Reformed religion and the third war of religion began. Chandieu's wife was forced to remain in France to avoid the confiscation of their properties. She visited him twice, and on the second visit, she gave birth to their fifth child, Suzanne, who was left in the care of her father.

In February 1570, he received news that his family was in danger and his château was occupied by the enemy. It was during this period he composed the Ode on the miseries of the French Churches. After years of desolation came a period of peace with the Treaty of Saint-Germain in August 1570 that brought to an end the third war of religion and accorded limited freedom of worship for Protestants. Chandieu returned to France and his family and participated in two national synods with Theodor Beza (l. 1519-1605) in La Rochelle and Nîmes during this time of peace. The brief respite was broken on 24 August 1572, with the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre. The carnage began in Paris and continued in the provinces. Like thousands of others, Chandieu once again took the route of exile to Geneva, this time for eleven years.

Later Years

Chandieu's next eleven years were spent in relative tranquility and the education of his children. The Academy of Lausanne invited him to the position of professor of theology in 1577. Two years later a plague ravaged Lausanne, forcing Chandieu and his family to leave for Aubonne, between Lausanne and Geneva, where he remained until July 1583. During this period of calm, he composed several of his writings. He translated his Meditations on Psalm 32 from Latin into French and dedicated it to the Protestants of France who had been forced to enter the Catholic Church.

The Treaty of Fleix in November 1580 ended the seventh war of religion and brought order and security to France. Chandieu left Aubonne for his home country in 1583 to visit his land holdings and establish himself at Poule. In September 1584, he was a delegate to a Reformed assembly permitted by Henry III of France (r. 1574-1589) at Montauban and returned home to devote himself to his theological writings.

The year 1584 began a new era of troubles that plunged France into another civil war. Henry of Navarre became the first in line to the throne at the death of Henry III's younger brother, François, Duke of Anjou (l. 1555-1584). In June, Chandieu left for Geneva for the safety of his family and returned alone to Poule. For the next three years, Chandieu served as chaplain to Navarre. He was one of the pastors who prayed before the Battle of Coutras in October 1587. This major engagement in the French religious wars ended in a great victory for the Huguenots, and Chandieu proclaimed the humiliation of the prince's enemies whose banners lined the victor's walls.

Chandieu's health suffered from life in military camps, and he fell gravely ill at Nérac in November 1587. Once recovered he was permitted to join his family the following spring in Geneva after a three-year separation. 15 days later, he was charged with missions to the cantons of Reformed Switzerland and the Protestant princes of Germany. With the assassination of Henry III in 1589, Henry of Navarre was designated his successor as Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610). Chandieu received his first letter from King Henry IV in January 1590; they continued correspondence and Chandieu retained a profound affection for him.

In his last years, Chandieu served the church in Geneva without remuneration, continued his theological writing, and corresponded with pastors in France. Along with Beza, his advice and opinions were sought for questions of doctrine and church discipline. He died on 23 February 1591.