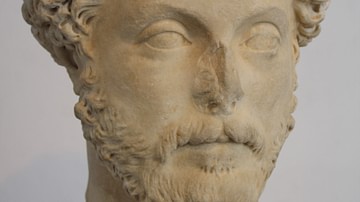

The Antonine Plague, sometimes referred to as the Plague of Galen, erupted in 165 CE, at the height of Roman power throughout the Mediterranean world during the reign of the last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (161-180 CE). The first phase of the outbreak would last until 180 CE affecting the entirety of the Roman Empire, while a second outbreak occurred in 251-266 CE, compounding the effects of the earlier outbreak. It has been suggested by some historians that the plague represents a useful starting point for understanding the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire in the West but also the underpinning to its ultimate fall.

Symptoms

Galen (129 - c. 216 CE), a Greek physician and author of Methodus Medendi, not only witnessed the outbreak but described its symptoms and course. Among the more common symptoms were fever, diarrhea, vomiting, thirstiness, swollen throat, and coughing. More specifically, Galen noted that the diarrhea appeared blackish which suggested gastrointestinal bleeding. The coughing produced a foul odor on the breath and an exanthema, skin eruptions or rash, over the entirety of the body distinguished by red and black papules or eruptions:

Of some of theses which had become ulcerated, that part of the surface called the scab fell away and then the remaining part nearby was healthy and after one or two days became scarred over. In those places where it was not ulcerated, the exanthem was rough and scabby and fell away like some husk and hence all became healthy. (Littman & Littman, p. 246)

Those infected suffered from the illness for roughly two weeks. Not all who caught the disease died, and those who survived developed immunity from further outbreaks. Based on Galen's description, modern researchers have concluded that the disease affecting the empire was most likely smallpox.

Cause & Spread of the Disease

The epidemic most likely emerged in China shortly before 166 CE spreading westward along the Silk Road and by trading ships headed for Rome. Sometime between late 165 to early 166 CE, the Roman military came into contact with the disease during the siege of Seleucia (a major city on the Tigris River). Troops returning from the wars in the East spread the disease northward to Gaul and among troops stationed along the Rhine River.

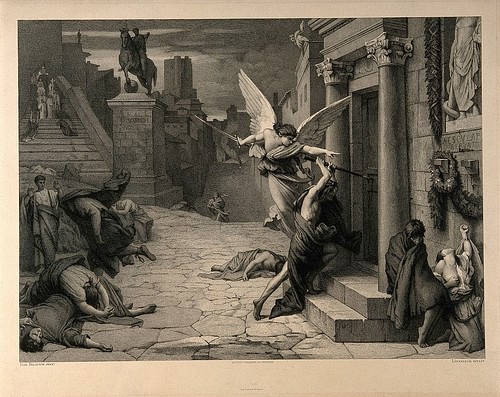

Two different legends arose discussing the exact origins of how the plague was released into the human population. In the first story, the Roman general, and later co-emperor, Lucius Verus opened a closed tomb in Seleucia during the subsequent sacking of the city thus releasing the disease. The tale suggests that the epidemic was a punishment as the Romans violated an oath to the gods not to pillage the city. In the second story, a Roman soldier opened a golden casket in the temple of Apollo in Babylon allowing the plague to escape. Two different 4th-century CE sources, Res Gestae by Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330-391 – 400 CE) and the biographies of Lucius Verus & Marcus Aurelius, ascribe the outbreak to participating in a sacrilege, violating the sanctuary of a god and breaking the oath. Other Romans blamed Christians for making the gods angry precipitating the outbreak.

Death Rate & Economic Effects

There is much ongoing debate amongst scholars regarding the effects and consequences of the epidemic on the Roman Empire. This debate is focused on the methodology used to compute the actual number of people who died. The Roman historian Dio Cassius (155-235 CE) estimated 2,000 deaths per day in Rome at the height of the outbreak. In the second outbreak, the estimate of the rate of death was much higher, upwards of 5,000 per day. It is most probable that the extreme death toll was due to this disease exposure being new to people living around the Mediterranean. Mortality rises when infectious diseases are introduced into a 'virgin population', that is a population which lacks acquired or inherited immunity to a specific disease. All told it has been suggested that a quarter to a third of the entire population perished, estimated at 60-70 million throughout the empire. What is undisputed is that Lucius Verus, co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius, died from the illness in 169 CE; Marcus Aurelius died 11 years later from the same illness. Ironically, it was Verus' soldiers who contributed to spreading the disease from the Near East to the rest of the empire.

At the outbreak of the plague, Rome's military consisted of 28 legions totaling approximately 150,000 men. The legions were well-trained, well-armed, and well-prepared, none of which prevented them from catching the disease, falling ill, and dying. Regardless of their posts, the legionaries contracted the disease from fellow soldiers who had been on leave returning to active duty. The ill and dying caused manpower shortages especially along the German frontiers thus weakening the Romans' abilities to defend the empire. The lack of available soldiers caused Marcus Aurelius to recruit any able-bodied man who could fight: freed slaves, Germans, criminals, and gladiators. Depleting the supply of gladiators resulted in fewer games at home, which upset the Roman people who demanded more, not less, entertainment during a time of intense stress. The patchwork army failed in its duty: in 167 CE, Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine River for the first time in more than 200 years. The success of the external attacks, especially by the Germans, facilitated the decline of the Roman military, which, along with the economic disruptions, contributed ultimately to the decline and fall of the Empire.

Effect on Religion

The effect of the illness was not confined to the military and economy. Marcus Aurelius launched persecutions against Christians who refused to pay homage to the gods which, the emperor believed, in turn angered the gods whose wrath made itself known in the form of a devastating epidemic. Ironically the anti-Christian attacks produced the opposite effect amongst the general population.

Unlike adherents to the Roman polytheistic system, Christians believed in an obligation to assist others in a time of need, including illness. Christians were willing to provide the most basic needs, food and water, for those too ill to fend for themselves. This simple level of nursing care produced good feelings between Christians and their pagan neighbors. Christians often stayed to provide assistance while pagans fled. Furthermore, Christianity provided meaning to life and death in times of crisis. Those who survived gained comfort in knowing that loved ones, who died as Christians, could receive the reward of heaven. The Christian promise of salvation in the afterlife attracted additional followers, thus expanding the growth of monotheism within a polytheistic culture. The gaining of adherents established the context in which Christianity would emerge as the sole, official religion of the empire.

Fall of the Empire

Any discussion of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West begins with Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Gibbon did not rule out the role of the effects of disease outbreaks; in regard to Justinian's Plague (541-42 CE), Gibbon argues early in his multi-volume work that “Pestilence and famine contributed to fill up the measure of the calamities of Rome”(Vol. 1., p. 91). Gibbon pays scant attention to the Antonine Plague, arguing instead that barbarian invasions, the loss of Roman civic virtue, and the rise of Christianity played the most important roles in the empire's decline.

More recently, researchers and historians, such as A. E. R. Boak, suggest that the Antonine Plague, along with a series of other outbreaks, represents a useful starting point for understanding the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire in the West. In Manpower Shortage and the Fall of the Roman Empire, Boak argues that the outbreak of plague in 166 CE contributed to a decline in population growth, leading the military to draft more peasants and local officials into its ranks resulting in lower food production and a lack of support for day-to-day affairs in administering the towns and cities, thus weakening Rome's abilities to fend off the barbarian invasions.

Eriny Hanna, in The Route to Crisis: Cities, Trade and Epidemics of the Roman Empire, argues that “Roman culture, urbanism, and the interdependence between cities and provinces” facilitated the spread of infectious disease thus creating the underpinnings for the collapse of the empire (Hanna, 1). Overcrowded cities, poor diets leading to malnutrition, and a lack of sanitary measures made Roman cities epicenters for disease transmission. The contagions easily spread along the land and sea trade routes which connected the cities to the outlying provinces.

Most recently, Kyle Harper suggests that "the paradoxes of social development and the inherent unpredictability of nature, worked in concert to bring about Rome's demise" (Harper, 2). In other words, climate change provided the environmental context for the introduction of new, more catastrophic diseases including the Antonine Plague which arrived at the end of a most favorable climate period and introduced the world to smallpox. Harper argues that the Antonine Plague was the first of three devasting pandemics, including the Plague of Cyprian (249-262 CE) and the Justinian Plague (541-542 CE), which rocked the foundations of the Roman Empire largely due to the high mortality rates. The very strengths which often characterize flattering descriptions of Rome's empire - the Roman army, the extent of the empire, the extensive trade networks, the size and number of Roman cities - ultimately provided the basis for devastating disease transmissions leading to the fall of the empire.