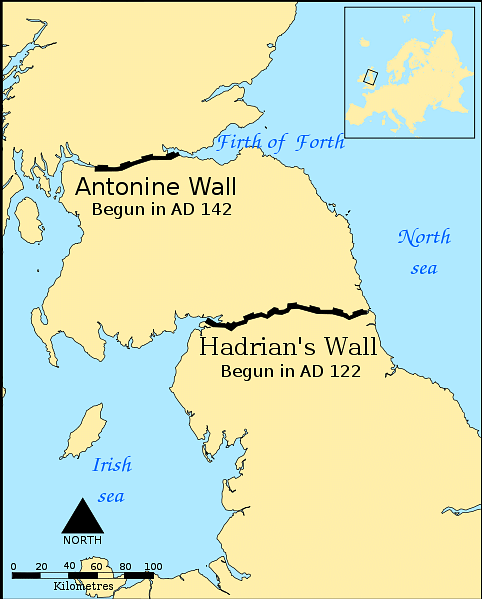

The Antonine Wall was the north-west frontier of the Roman Empire. Located in central Scotland, north of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the Wall was a linear barrier that stretched from the Firth of Forth near Bo'ness to the Clyde estuary at Old Kilpatrick. Chronologically, the Antonine Wall post-dates the initial construction of Hadrian's Wall and was probably constructed in the early 140s CE, on the orders of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE), who assumed the throne upon Hadrian's death.

Purpose

The Wall was a rather short-lived imperial frontier, and the preponderance of evidence suggests that it was abandoned by the early 160s CE when Hadrian's Wall was recommissioned. While limited—and unstratified—finds have been dated to later periods, and there is evidence for continued Roman activities up to and beyond the Wall (as, for example, with the short campaigns of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century CE), the archaeological evidence strongly favours the view that the Antonine Wall was never recommissioned or reoccupied by the Roman army after the early 160s CE. It can be seen, then, as a frontier that had its origins, functional life, and end probably entirely within the roughly two-decade reign of Antoninus; it is, thus, quite appropriate that it is now known by the name the "Antonine Wall."

Architecture

As with many other frontiers, the Antonine Wall was a complex of various interconnected features. These can be classified as either linear components that stretch along most of the Wall's length or as additional installations occurring at specific points along this line. While public perception of the term "wall" often revolves around an enclosing structure or rampart—generally of timber, stone, or brick—the term "Antonine Wall" is used by scholars and heritage managers to refer to a collection of inter-related features of which a rampart or "wall" is but one. This is similar to Hadrian's Wall, where the monument consists of more than the stone curtain, including the Vallum and its associated mounds, the northern ditch, berm and mound, forts, milecastles, towers, turrets, and other installations.

The Wall was composed of several linear features that ran almost continuously from one end to the other, including the Military Way (or Roman road), Rampart, Berm, Ditch, and Outer Mound. One calculation suggests that work on all of these linear features may have been completed in only about eight months, though it is possible that work was spread across several seasons. Unlike with Hadrian's Wall, the Antonine Wall's Rampart was not constructed of stone but, rather, turf or earth revetted by clay or turf cheeks atop a kerbed stone base. Unsurprisingly, this superstructure has not survived very well and, for most of the length of the Wall, the Rampart is no longer visible on the surface, with the Ditch representing the most identifiable linear feature. Because of this lack of preservation, how the top of the Rampart was finished remains unknown: it was probably squared flat on top and may have featured stakes set into the top, or, "more probably, the flat top was covered by a wooden duckboard walk, and along the north edge...there could have been a wooden breastwork or palisade" (Robertson 2001, 11). While there is some evidence that the original plan may have been to build (or eventually rebuild) the Rampart in stone, this was never acted upon.

The Wall also featured a range of installations, including at least 17 forts (out of a hypothesised total of 19) and a number of intervening fortlets (of which nine are currently known, but which may have been located at intervals of one Roman mile). Most forts have been found to include an additional fortified space, called an "annexe." The precise purpose and nature of these annexes remain uncertain; in some cases the annexe is significantly larger in area than the fort itself, and these are likely to have been later additions; few have been excavated, though several have produced the remains of Roman baths. In fewer locations, there is evidence for additional activity or settlement outside of the fort and annexe, probably representing the non-military civilian settlements, or vici, and it is possible that the annexes played a dual role, serving both the military and civilian communities.

Inscriptions

19 or 20 inscribed stone tablets, most discovered before the 20th century CE and two subsequently lost, record the work of building the Wall. Known as "distance slabs," these stones bear an inscription honouring the emperor Antoninus Pius, and record the name of the responsible legion and the completed distance. It has been suggested that there may have been as many as 60 of these inscriptions and, while building inscriptions are common throughout the Roman world, the Wall's distance slabs are in a class of their own, being not only inscriptions but often elaborate sculptures. The closest parallels on Hadrian's Wall or the German Limes are far simpler, recording only the emperor and responsible military unit without the ornate details or noted distances. Importantly, two of the slabs refer to the commemorated task as opus valli, "the work of the wall," suggesting that they may refer specifically to the construction of the Rampart itself. Total construction of the Wall, its various linear features, forts and other installations may have taken twelve years or more to complete.

The Wall also has a rich post-Roman history, with several medieval castles being built on its line, and a coast-to-coast canal (the Forth and Clyde Canal) being constructed parallel to and across it during the Industrial Revolution. These periods have received far less attention by historians and archaeologists than the roughly 20-year period of the Wall's functional life as a frontier in Roman Britain.