Apis was the most important and highly regarded bull deity of ancient Egypt. His original name in Egyptian was Api, Hapi, or Hep; Apis is the Greek name. He is not, however, associated with the god Hapi/Hep who was linked to the inundation and is depicted as the god of the river.

Worship of the Apis bull is recorded as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3150 - c. 2890 BCE) in ceremonies known as The Running of Apis but veneration of the bull in Egypt precedes this time, and so it is thought that Apis may be the first god of Egypt or, at least, among the first animals associated with divinity and eternity. He was originally a god of fertility, then the herald of the god Ptah but, in time, was considered Ptah incarnate. He was also, in some eras, depicted as the son of Hathor and was closely associated with her goodness and bounty.

There were many bovine deities in ancient Egypt, Hathor simply being the best known, but Apis was the most significant because he represented the core cultural values and understanding of all Egyptians. Each individual deity had their own sphere of influence and power, but Apis represented eternity itself and the harmonious balance of the universe. Other bovine deities such as Bat, Buchis, Hesat, Mnevis, and the Bull of the West, no matter how powerful, would never have the same resonance as the incarnated deity of the Apis bull.

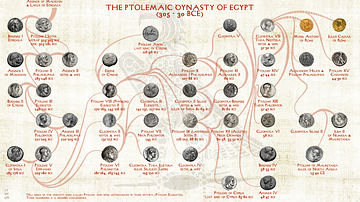

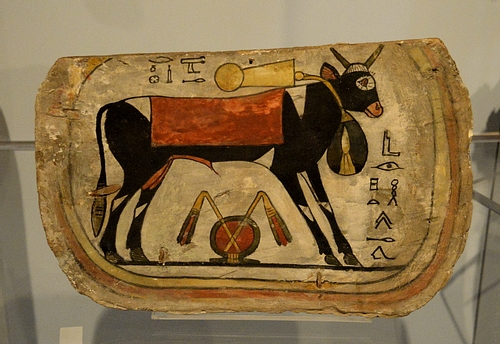

Apis is depicted throughout Egypt's history as a striding bull, usually with a solar disc and uraeus (the sacred serpent which symbolized the king's power) between its horns. In the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE) he is sometimes depicted as a man with a bull's head, and, in Roman Egypt, this becomes the most popular representation of the god. During the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), which comes between these two, he was represented in anthropomorphic form as a bearded man in robes, much in the fashion of Greek gods like Zeus, under the name Serapis. The Apis bull was always associated with the king of Egypt and, among its many meanings, represented the strength and vitality of the reigning monarch.

Origin & Selection

There are no myths related to the origin of Apis, but he is attested to through engravings from the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE). Apis was a god of fertility and primordial power who then came to be associated with the creator god Ptah. At what point he first became linked with Hathor is unclear, but this association is established firmly by the time of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE), during which time the bull was also linked to the power of the king (as evidenced on the Narmer Palette). The Apis bull was worshiped ceremonially from this era through the Ptolemaic Period and on into the Roman Period consistently no matter which other deities were in vogue at a given time. During different eras of Egypt's history various gods assumed supremacy in different regions, or even nationally, such as Osiris, Isis, Amun, Atum, Ra, but the worship of Apis never dramatically changed.

In the Early Dynastic Period, the ritual known as The Running of Apis was performed to fertilize the earth. The bull is shown in engravings wearing the menat, the necklace/collar sacred to Hathor. Where the bull ran during this ceremony is unclear, but most likely, it was in the temple precinct at Memphis, the capital of Egypt at the time, which would symbolically fertilize all the land.

The bull was selected, after a careful search, based upon its appearance: it had to be black with a white triangular marking on its forehead, another white marking on its back in the shape of a hawk's or vulture's wings, a white crescent on its side, a separation of the hairs at the end of its tail, (known as the "double hairs") and a lump under its tongue in the shape of a scarab. If a bull were found with all of these characteristics, it was instantly recognized as Apis, of course, but even a few or one would suffice. A white marking in the shape of a triangle on the forehead and the scarab-shaped lump under the tongue were often enough for the bull to be chosen.

Worship

Once selected, the bull was brought to Memphis and housed in the temple precinct along with his mother. People would travel to the city from all over the land to worship the animals. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson describes the bull's life in the city:

In Memphis the Apis bull was kept in special quarters just south of the Temple of Ptah where it was adored by worshippers and entertained by its own harem of cows. In addition to its participation in special processions and other religious rituals, the animal was utilized in the delivery of oracles and was regarded as one of the most important oracular sources in Egypt. (172)

On feast days, festivals, and other special events like a king's coronation, the bull was turned loose in a special chamber with different gates leading from it. Symbols and foodstuffs were placed on the other side of the chamber's gates, and people would ask questions regarding the future while the bull was led into the room. Whichever gate the bull chose to go through would provide an answer to the people's questions.

Once the oracle had been given and interpreted by the priests, the bull was allowed to roam at will within the enclosure while the people knelt before it in worship. To the ancient Egyptians, every kind of life was an extension of the divine and all of life was sacred. Although the Egyptian diet did include meat, it was largely vegetarian, and when animals were eaten, thanks were offered for the sacrifice.

Although the people would have known that this particular bull they were seeing would die, they also knew that the spirit which inhabited that bull was eternal; a particular bull's body might die but not the bull itself, not the soul which animated the animal. It was this eternal aspect of the Apis bull which made it so significant at religious festivals and other public gatherings.

One of the most important events the bull participated in was the Heb-Sed Festival, held every thirty years of a king's reign in order to rejuvenate him. The Heb-Sed Festival included a number of physical acts the king had to perform to show he was still fit to serve the gods and the people. The bull, from earliest times, had been associated with the king and monarchial power, and so the Apis bull would walk beside the king as a show of divine approval. At the conclusion of the festival, when the people were invited to a communal feast in honor of the king, the Apis bull would remain in the king's presence as a continual reminder of power and virility.

Death & Replacement

After a period of 25 years, if the bull suffered no disease or accident, it was ceremonially killed. Certain parts of the animal were eaten by the priests, and then the carcass was taken to a special part of the temple precinct at Memphis to be embalmed. A state of mourning was decreed during which the bull's body was mummified with the same care given a king or noble, and at this same time, priests were sent out to find a replacement. Once the embalming was completed, the mummified bull was conveyed along the sacred way from Memphis to the necropolis at Saqqara where it was buried in the Serapeum, a subterranean series of chambers dug for this purpose under by the fourth son of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE), Khaemweset. It was also Khaemweset, who was devoted to preserving history, who ensured the careful recording of the deaths of Apis bulls and date of burial. As High Priest of Ptah at Memphis, Khaemweset would have presided over the funeral ceremonies for the bulls.

Bulls were buried in granite sarcophagi, some of which were ornamented, while the bull's mother - who had also been ritually killed and embalmed - was buried in a similar style in the Iseum catacombs dedicated to Isis. Any calves the bull had produced were likewise killed and embalmed, although their burial place is unknown.

The reason for the bull's death was to join it with Osiris and ritually re-enact the cycle of life, death, and resurrection. The bull had represented the living creator Ptah while it lived and became Osiris when it died and was then referred to as the god Osirapis. Osiris was the first king of Egypt, and the first to die and return to life among all sentient beings, and therefore the ritual act of killing the animal which was so closely associated with kingship and the divine merged the monarchy with resurrection. The death of the Apis bull symbolized the eternal nature of life. Instead of waiting for the bull to die of old age or disease, it was sent to Osiris while still fit, and after it was entombed, a bull looking very much like the last took its place. This new bull would, in fact, house the same eternal spirit as the last since it was believed that the soul of the old bull was reborn in the one that would be chosen to replace it.

It was for this reason that, at the beginning of the Ptolemaic Period, Ptolemy I chose to merge Apis with the Greek god Zeus and others to create his new god Serapis for the multicultural society he was trying to form in Egypt. Ptolemy I built his great Serapeum in Alexandria, nearby the famous library, to elevate his new god as a deity who embraced and welcomed everyone. Apis was not just another god in the Egyptian pantheon but the embodiment of Egyptian values, and once Ptolemy I merged him with Greek divinities, he became the pre-eminent god of the nation who died only to live eternally. The bull's death was not the end of its life but a moment of transition from one state to another, and the ceremony which involved its killing was not considered slaughter but transformation.

This ritual might seem to contradict the value ancient Egyptians placed on individuality and a long, full life but, actually, it illustrated that very concept. The bull would never grow old and die - it was an eternal being - and it would remain eternally fit and healthy passing from one body to another in an endless progression. The reason the worship of the Apis bull never significantly altered in over 3,000 years is because it embodied the deepest Egyptian values concerning life, time, and eternity. One's time on earth was only a brief sojourn in an eternal journey which would take one out of time but not out of place. The Egyptian afterlife was a continuation of life on earth, only on a different plane; one would still enjoy one's home, pets, land, and loved ones in paradise. The Apis bull assured people of this by its constancy; no matter the era in which one lived, there had been this divine manifestation before, there was one at the present, and there would be one in the future, and all would be the same entity eternally.

Cambyses II & Christianity

In 525 BCE the Persians under Cambyses II invaded Egypt, and Herodotus reports that Cambyses II himself killed the Apis bull before its allotted time (a story also told by Diodorus Siculus) and had the carcass flung into the street where it was eaten by dogs. These accounts have been challenged because Cambyses II knew and respected Egyptian culture and so it seems out of character to some scholars that he would knowingly commit such a sacrilege.

Actually, however, the story is not so hard to believe. Cambyses II had only recently conquered Egypt at the Battle of Pelusium by using the Egyptian's own beliefs against them. Knowing their veneration for animals generally, and the cat in particular, he had his soldiers round up as many stray animals as possible and paint the image of the Egyptian cat goddess Bastet on their shields. He then marched on Pelusium, driving the animals before his forces and demanded the city's immediate surrender. The Egyptians complied rather than risk hurting the animals and enraging Bastet. There seems little difference between Cambyses II's actions here and his later killing of the Apis bull. In both instances he was making use of Egyptian belief for his own ends: by slaying the Apis bull before its time he was announcing himself as the new king of Egypt and dismissing the old Egyptian monarchy, and rituals concerning it, to highlight his triumph and the dawn of a new regime.

Herodotus goes on to explain how Cambyses II paid for his crime with his life; as he was mounting his horse, he accidentally stabbed himself in the thigh - in the same place where he had first pierced the bull - and died from an infection. It is also reported that dogs were viewed as unclean animals from this point on because they had eaten the divine bull. Dogs were always regarded highly in Egypt, the story goes, but were now looked down upon as vile. There does not seem to be any evidence to support this claim, however, since dogs continue to be kept for hunting, as guardians, and companions throughout the rest of Egypt's history without any noticeable decline in status.

The Apis cult continued until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE. The eternal bull who symbolized Egyptian values was incompatible with the new Christian vision, and the rituals surrounding the bull declined. The Serapeum of Ptolemy I was destroyed by zealous Christians c. 385 CE in their efforts to eradicate pre-Christian beliefs in Alexandria. This same zeal may have also resulted in the destruction of the great library, located near the Serapeum, at the same time or a little later. In the 5th century CE, the Apis cult was banned along with other pagan sects and rituals as the Christian understanding of the universe and divinity became dominant.