Apollo was a Greek god associated with the bow, music, and divination. The epitome of youth and beauty, source of life and healing, patron of the arts, and as bright and powerful as the sun itself, Apollo was perhaps the most loved of all the gods. He was worshipped at Delphi and Delos, amongst the most famous of all Greek religious sanctuaries.

Son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, Apollo was born on the island of Delos (in Hesiod's Theogony he is clutching a golden sword). His mother, fearful of revenge from Zeus' wife Hera, had chosen barren Delos as the safest retreat she could find. At his first taste of ambrosia, he was said to have immediately transformed from babe to man. Apollo was then given his bow, made by the master craftsman of Mount Olympus, Hephaestus.

As with the other major divinities, Apollo had many children; perhaps the most famous are Orpheus (who inherited his father's musical skills and became a virtuoso with the lyre or kithara), Asclepius (to whom he gave his knowledge of healing and medicine) and, according to the 5th-century BCE tragedian Euripides, the hero Ion.

In Mythology

Apollo is a significant protagonist in Homer's account of the Trojan War in the Iliad. On the side of the Trojans, he gives particular assistance to the Trojan heroes Hector, Aeneas, and Glaukos, saving their lives on more than one occasion with his divine intervention. He brought plague to the Achaeans, led the entire Trojan army (holding Zeus' fearsome aegis) in an attack which destroyed the defensive walls of the Greek camps, and was also responsible for guiding Paris' arrow to the heel of Achilles, killing the seemingly invincible Greek hero. Apollo is most frequently described by Homer and Hesiod as the 'far-shooter', the 'far-worker', the 'rouser of armies', and 'Phoebus Apollo'.

Apollo generally played the dutiful son to Zeus, father of the gods, and never attempted to usurp his position (unlike Zeus who had overthrown his own father Cronus). The pair did have a serious falling out when Zeus killed Asclepius after he had used his marvellous medicinal skills to bring a mortal back to life. In revenge, Apollo then killed the Cyclopes, the one-eyed giants who made Zeus' thunderbolts. As punishment, Apollo was obliged to spend a year in the humble service of Admetus of Therae, tending the king's sheep.

Apollo acquired his lyre from his mischievous half-brother Hermes, the messenger god. While still a baby, Hermes had stolen Apollo's sacred herd of cattle, cleverly reversing their hooves to make it difficult to follow their tracks. Hermes was permitted to keep his ill-gotten gains but only after he gave Apollo his lyre which he had invented using a tortoiseshell.

Apollo's Darker Side

Apollo's darker side as the bringer of plague and divine retribution is seen most famously when he is, with his sister Artemis, the remorseless slayer of Niobe's six (or in some accounts seven) sons as punishment for her boasting that her childbearing capacity was greater than Leto's. Another hapless victim of Apollo's wrath was the satyr Marsyas who unwisely claimed he was musically more gifted than the god. The pair had a competition and the Muses ruled that Apollo was indeed the better musician. Apollo then had the mortal flayed alive for his presumption and nailed his skin to a pine tree. The tale is an interesting metaphor for the competition between (at least to Greek ears) the civilised and ordered music of Apollo's lyre and the wilder, more chaotic music of Marsyas' flute. Apollo won another musical competition, this time against the pastoral god Pan and, judged the victor by King Midas, Apollo thus became the undisputed master of music in the Greek world. The god's defeat of Marsyas and Pan may reflect the Greek conquest of Phrygia and Arcadia respectively.

What is Apollo Associated With?

Objects traditionally associated with Apolllo include:

- a silver bow - symbolic of his prowess as an archer.

- a kithara (or lyre) - made from the shell of a tortoise, this was symbolic of Apollo's ability in music and his leadership of the chorus of the nine Muses.

- a laurel branch - symbolic of the fate of Daphne who, after Apollo's amorous pursuit of her, led her father, the river god Phineus, to transform her into a laurel tree.

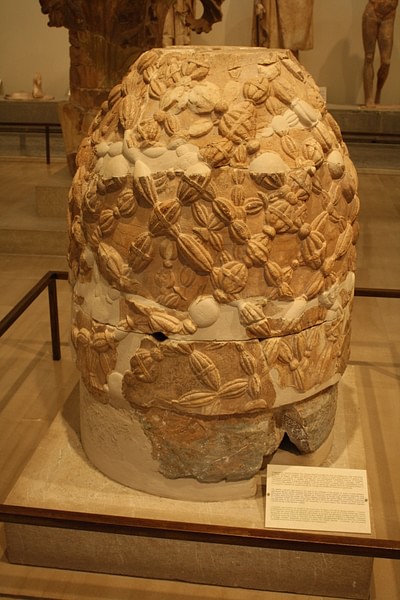

- the omphalos - symbol of Apollo's sanctuary at Delphi as the navel of the world.

- a palm tree - which Leto gripped when she gave birth to her son.

Apollo was a much-loved god, and this was most likely due to his association with many positive aspects of the human condition such as music, poetry, purification, healing, and medicine. The god was also associated with moderation in all things. His arrows, although they could bring destruction could also ward off harm to those he favoured. A strategy to keep away evil from Greek homes was to set up a pillar of Apollo Agyieus and, on a grander scale, Apollo Propylaios protected city gates.

Apollo oversaw the initiation rites performed by young males (ephebes) as they entered the full civic community and became warriors. Rituals in this process involved cutting hair and offering it to the god, as well as athletic and martial challenges. The god is frequently associated with the sun (as Phoebus Apollo) and the sun god Helios, but modern scholars mostly agree that the link between Apollo and Helios does not go further back than the 5th century BCE. Apollo continued to inspire the Romans when he was principally considered a god of healing. Octavian, the future emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE), famously claimed the god as his patron and even dedicated a temple to Apollo at Actium. The god of moderation was a useful association and in direct contrast to the god of excess, Dionysos, championed by Octavian's no. 1 enemy, Mark Antony.

Which Sites Were Sacred to Apollo?

Sanctuaries were built in honour of Apollo throughout the Greek world, notably at the islands of Delos and Rhodes and at Ptoion and Claros. Sites which still possess some vestiges of once-great temples dedicated to Apollo include those at Naxos (6th century BCE), where the massive doorway still stands proud, at Corinth (550-530 BCE), where seven Doric columns give an impression of a once impressive structure, at Didyma, Turkey (4th century BCE), whose temple was the fourth largest in the Greek world, and at Side, also in Turkey (2nd century CE) where a corner of its elegant columned facade has been restored.

Apollo's most direct presence amongst the Greeks, though, was manifested in his oracle at Delphi, which was consulted for its prophetic powers and which was the most important in the Greek world. According to legend, Apollo, wishing to reveal to humanity the intentions of his father Zeus, created the oracle on the site where he had killed the serpent (or dragon) Python. The Panhellenic Pythian games were begun at the site in order to commemorate the death of this divine creature. Tripods and laurel wreaths were given as prizes to the victors at these games. The 30 treasuries built at Delphi by various cities indicate the popularity of the god and the sanctuary in the wider Greek world such as in Asia Minor.

The oracle of Delphi was already well-visited in the 8th century BCE - despite being difficult to get to and open only in summer - and the sometimes cryptic proclamations of its priestesses were not taken lightly, often deciding how laws would be applied or whether a foreign war should be pursued. Sometimes the oracle's responses to questions were so obscure that priests at the site offered (for a fee) to give them greater clarity. As the historian B. Graziosi summarises,

Pilgrims often continued to ponder Apollo's responses, and consult further experts, back home. After that long process of consultation and interpretation, Apollo's revelations usually crystallised into lines of hexameter poetry, and were always found to be true - even if the correct interpretation sometimes emerged only after the relevant events had come to pass. (21)

How is Apollo Represented in Art?

Apollo appears frequently in all media of ancient Greek art, most often as a beautiful, beardless youth. He is easily identified with either a kithara or a lyre, a bronze tripod (signifying his oracle at Delphi), a deer (which he often fights over with Hercules), and a bow and quiver. He is also, on occasion, portrayed riding a chariot pulled by lions or swans.

Perhaps the most celebrated representation of Apollo in ancient Greek art is the statue which dominated the centre of the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (c. 460 BCE). Here, in a majestic pose, he brings order and reason to the battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the wedding of Peirithoos. Another fine example of Apollo in his guise as a handsome youth, this time with long locks, is a 2nd-century CE marble relief from a funerary monument in Piraeus. The head of Apollo frequently appeared on Greek coins, notably on the silver tetradrachms of 5th-century BCE Catane (Catania) in Sicily and the gold staters of Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-356 BCE).

Roman sculptors were also fond of Apollo and a celebrated marble statue of the god, now in the Vatican Museums in Rome, is the Apollo Belvedere, a 2nd-century CE copy of a bronze statue of the 4th-century BCE by Leochares. Even the Etruscans were at it, perhaps one of their most famous sculptures in terracotta being the Apollo of Veii (late 6th century BCE), a striding figure of the god, known to them as Aplu, which once stood on the roof of a temple.