The Arapaho are a North American Native nation originally from the Red River Valley in modern-day Manitoba, Canada, and Minnesota, USA. They migrated south in the early 18th century and established themselves in modern-day Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, Wyoming, and points south. They are associated with the Plains Indians culture and have long been allies of the Cheyenne.

The Arapaho adopted an agrarian lifestyle early, which was then modified when they were introduced to the horse by French traders. Able to travel further on hunts now, they gradually became a nomadic people and, pressured by the Ojibwe expansion in the Great Lakes region, moved south. Scholar Adele Nozedar writes:

When the [United States] settlers first came upon them, the Arapaho were already expert horsemen and buffalo hunters. Their territory was originally what has become northern Minnesota, but the Arapaho relocated to the eastern Plains areas of Colorado and Wyoming at about the same time as the Cheyenne; because of this, the two people became associated and are also federally recognized as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

(25)

The Arapaho speak the Arapaho language (part of the Algonquian language group) and continue to practice their traditional, animistic, religion today as they did in the past, although many now blend the ancient spiritual beliefs with Christian rites and rituals. They were among the Plains Indians who participated in the Sun Dance (which they referred to as the Offerings Lodge) in the 19th century and still observe the ritual today at the Northern Arapaho Reservation of Wind River in Wyoming.

Like other nations of the Great Plains, and elsewhere, the Arapaho clashed with the Euro-American settlers migrating west in the mid-19th century. Allied with the Cheyenne and Sioux, Arapaho warriors took part in the Colorado War (1864-1865), Red Cloud's War (1866-1868), and the Great Sioux War (1876-1877), among other conflicts. The Southern Arapaho were camped with the Southern Cheyenne under Chief Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868) when they were attacked by US cavalry in what is now known as the Sand Creek Massacre (29 November 1864), which only strengthened their resolve to defend their ancestral lands against invasion by White settlers from the United States.

Even so, by 1868, both the Northern and Southern Arapaho understood the futility of continuing the fight against overwhelming forces and agreed to move onto reservations (which is one of the reasons so few Arapaho were present at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876). The Southern Arapaho were relocated to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) while the Northern Arapaho were moved to the reservation of the Shoshone, their traditional enemies, in Wyoming.

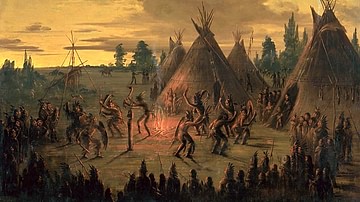

Like the Pawnee, the Arapaho were allowed to continue to observe the Ghost Dance, initiated by the Paiute Nation in 1889, after the US government prohibited other nations, notably the Sioux, from doing the same. The songs and rituals that accompany the Ghost Dance enabled the Arapaho to retain much of their culture, and both Northern and Southern Arapaho continue these traditions today.

Name & Nation

The name Arapaho was given to the people by European colonists who mispronounced the name given them by the Crow nation – Alappaho ("Many Tattoos"), which the people then began to apply to themselves. They originally called themselves Hinono'eino ("the people" or "our people"). The Cheyenne referred to them as Hitanwo'iv ("People of the Sky"), but the reason for this is unclear.

In the 18th century, the Arapaho nation consisted of five bands, each with their own dialect of the Algonquin Arapaho language:

- Beesowuunenno (Big Lodge People)

- Hanahawuuena (Rock People)

- Hinanae'inan (Arapaho Proper)

- Nawathi'neha (Southern People)

- Haa'ninin (White Clay People - better known as Atsina and Gros Ventre)

The Gros Ventre split from the other bands in the early 18th century and were later regarded as inferior by the Arapaho. The Arapaho nation was then defined by the four remaining tribal bands, who separated into the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho with the northern band holding the position of the "mother tribe" responsible for the safekeeping of sacred objects such as the ceremonial flat pipe.

Government & Daily Life

The Arapaho government in the 19th century was led by a council of four elders, representing each band, who supervised age-graded societies that made up the Arapaho community. These council members were chosen by consensus based on strength of character, insight, and wisdom. There was also a council of elderly wise women who were consulted prior to decisions concerning the nation or the various societies. One was born into a family of a given society but, at an early age, had to take a spiritual vow to commit to that group's (or another's) responsibilities. As one grew up, one took another vow and then another along with one's peer group as young men entered the next level of their society. Young girls and women belonged to the society of their fathers until they were married and then progressed up the social ladder as their husbands did.

These societies had various responsibilities including enforcement of the decisions of the council, maintaining the peace and order in the village, organizing hunting or war parties, and defense of the village/community. Although the Arapaho of the 19th century are often characterized as a peaceful people, more concerned with spiritual matters than secular concerns, they were actively engaged in warfare with many other Native peoples of North America, including the Apache, Arikara, Blackfoot Confederacy, Crow, Gros Ventre, Pawnee, and Ponca. The military societies of the Arapaho were similar to those of the Cheyenne in that they had their own symbols and rituals and were each led by their own war chief or chiefs.

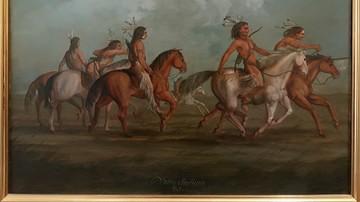

One became a war chief, not only by showing courage in battle (primarily through "counting coup" – touching or striking an enemy without killing him) but by evidence of spiritual development as shown by wise decisions, patience, generosity, and exceptional skill at warfare. The Arapaho were long-acquainted with firearms, having traded for them with French settlers as early as the 1700s, about the same time they were introduced to the horse, and so were formidable warriors who had mastered the use of several weapons while on horseback, aside from firearms, including the lance, bow and arrow, tomahawk, knife, war club, and, of course, the coup stick, used in counting coup.

Arapaho women were responsible for raising the children, tending crops, cooking meals, making clothing and footwear, building the lodge (or raising the tipi), creating ornaments, amulets, and charms, and making saddles and tack for horses. Children were raised by their female relatives until the age of four or five when boys began to be instructed by their male relatives. The Arapaho also recognized a third gender – the haxu'xan ("Two-Spirit") – men who dressed and acted like women. The haxu'xan had the same responsibilities as the women. One of the most popular figures from Arapaho folklore is Nih'a'ca, the first haxu'xan, often depicted as a trickster who – like Wihio in the Cheyenne Wihio tales or Iktomi in the Sioux Iktomi tales – winds up being tricked. The Nih'a'ca tales are among the most popular legends of the Arapaho.

Daily life consisted of harvesting crops (if the village were a permanent settlement), maintenance of the home and village, hunting, food preparation, mending clothes, repairing homes or communal lodges, sports – usually team sports like chunkey or stickball – and spiritual observances which, apart from one's personal devotions, took the form of festivals and community-wide rituals, such as the Sun Dance.

Religion, Ritual, & Afterlife

According to the Arapaho Creation Story, the world was made from the mud brought up from the bottom of the endless waters. The Creator, Be He Teiht ("Great Spirit"), is sometimes given as the central character in the act of creation while, in other versions of the story, the Great Spirit inspires another entity known as either Father, Pipe Person, or Flat Pipe who sends various animals down to the bottom of the waters to bring up the essential mud. Most of the animals fail, but the duck and turtle succeed, and Father (or the Great Spirit) then creates earth, the sun, the moon, and humans. Some animals had been created already, and once the earth was made, Father brought forth land creatures. All living things, created by the same sentient power, are therefore related as family, and live together in what the Arapaho call the World House.

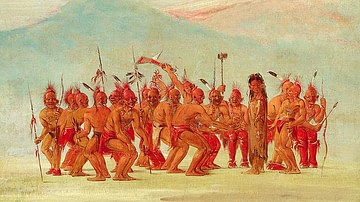

The World House came into being before the earth was made through the prayer-thought of the Creator. A prayer-thought is the expression of a desire so strong it can alter reality, and, by communing closely with the Creator, people can tap into this same energy and use prayer-thoughts to improve their lives and those of their family and wider community. This practice became part of the Arapaho Sun Dance ritual (Offerings Lodge Ceremony) during which participants would petition the Great Spirit for gifts or favors, for healing and recovery, or would give thanks for gifts given, through the power of prayer-thought which was understood to make that request, or expression of gratitude, more potent.

The Arapaho did not engage in the self-torture aspect of the Sun Dance, as the Sioux did, but substituted that with "flesh offerings" – self-cutting – as described in the Arapaho myth The Woman and the Monster, by which one shows one's devotion and respect through personal sacrifice usually given for the greater good. The self-cutting of the "flesh offerings" was not considered the same thing as self-torture, which was a public event, and those who did not wish to cut themselves could choose another way to express piety, often by donating land or personal items to the community.

The flat pipe – said to have been present at the act of creation – is central to the Arapaho Sun Dance as it is to all their other rituals and festivals. Similar to the Sioux ceremonial pipe, the Arapaho flat pipe was given to the people by a supernatural entity, in this case, the Father (the spirit of the Arapaho people) who drew on the power of the pipe for the prayer-thought that enabled creation.

The Arapaho vision of life after death is similar to the Cheyenne afterlife in that, after death, one will return home to the Father and the Great Spirit where one will find villages just like those one knew on earth and be reunited with those who have gone before. This belief was central to the appeal of the Ghost Dance to the Arapaho in 1889-1890 because, by engaging in the ritual, one was believed to be tapping into the spirit world to bring back those one had lost – not only people but animals like the buffalo herds that had been systematically exterminated by White settlers – and could help return the world to its natural state of balance before the arrival of the Europeans. Arapaho, Cheyenne, Sioux, and Paiute participants claimed to have received visions of the afterlife during the Ghost Dance and to have seen their departed relatives and the buffalo as plentiful as they once were before the invasion by the White people.

Conflict & Sand Creek Massacre

Conflict between Euro-American settlers and the Plains Indians had been ongoing since 1823 and worsened in 1848 when the California Gold Rush created a stampede of miners and settlers across the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux lands. These immigrants regularly killed buffalo, the Native Americans' prime source of food, clothing, and other necessary items, scattered the herds, and tore up the prairie with their wagons and cattle. The Native Americans responded by trying to drive them off in a series of skirmishes and raids.

These clashes led to the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which established territories for each nation – which the treaty made clear the US had no claim to – as well as lands that could be safely traveled, or settled, by Euro-Americans. Among the Native American signers of the treaty were Black Kettle of the Southern Cheyenne and Chief Niwot (Left Hand, l. c. 1825-1864) of the Southern Arapaho. The treaty was ignored by the US government, and the settlers almost immediately after the signing and was broken completely in 1858 during Pike's Peak Gold Rush, which brought further conflict, raids by Native American war bands, and destruction of lands and homes.

Another attempt was made through the Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861, which proved as useless as the Fort Laramie Treaty as the US government and its citizens again ignored all of the provisions. Among these was that Native American bands who agreed to relocate to designated reservations would receive provisions, supplies, and tools for farming – but none of these were delivered. The people were starving, and so Cheyenne chiefs, including Tall Bull and Roman Nose (Cheyenne Warrior), and Arapaho chiefs, including Chief Black Bear and Medicine Man, took it upon themselves to raid settlements and wagon trains for food and other necessities. These raids, and US responses, came to be known as the Colorado Wars.

The Arapaho and Cheyenne had already been designated 'hostiles' by the US government, but the situation worsened after the Hungate Massacre of June 1864 when the Hungate family near Denver, Colorado were killed in a raid and their home burned. Although there was no evidence linking the Arapaho or Cheyenne to the massacre (and some evidence they had nothing to do with it), Governor John Evans (l. 1814-1897) gave Colonel John Chivington (l. 1821-1894) complete freedom to kill any Arapaho or Cheyenne he found. On the morning of 29 November 1864, Chivington attacked Black Kettle's village at Sand Creek, which was flying both the American flag and the white flag of truce, killing over 150 Arapaho and Cheyenne, mostly women, children, the elderly and infirm. There was no evidence of any raiders who might have struck the Hungate home in the village.

Chief Niwot was among the dead, but Black Kettle escaped and continued to advocate for peace along with the other 'peace chiefs', both Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Sand Creek Massacre had greatly diminished the standing of the peace chiefs, however, and war chiefs like Black Bear, Medicine Man, Roman Nose, and Tall Bull now had more prestige. The war chiefs continued their resistance to US domination until 1867 when the Southern Arapaho under Chief Little Raven (l. c. 1810-1889) signed the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek. The Northern Arapaho continued the fight until 1868 when Medicine Man and Black Bear surrendered and agreed to move onto a reservation. Black Kettle was killed that same year at the Washita Massacre, another unprovoked attack on a Native American village, and Black Bear, along with almost 20 others, was murdered two years later in 1870 by a group of vigilantes who were 'hunting Indians' in retaliation for a raid on a mining site.

Conclusion

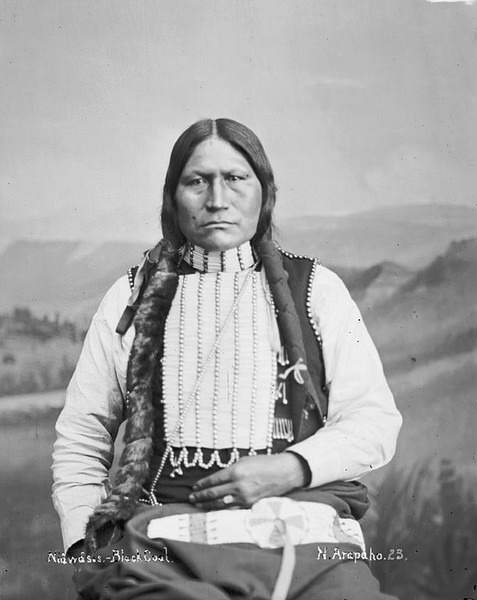

By 1870, when both Southern Arapaho and Northern Arapaho were on reservations, Roman Nose and Tall Bull had both been killed in battle, along with many other Cheyenne and Arapaho. Little Raven still sought peace for his people and so tried to keep them out of the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Chief Black Coal (l. c. 1840-1893) pursued the same path as chief of the Northern Arapaho, but neither could prevent some of their warriors from joining with the Cheyenne and Sioux. It is generally accepted that there were only five Arapaho warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and one of them, Water Man (d. c. 1920) claimed to have witnessed the death of Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876), though this has been challenged.

In 1890, the Arapaho joined the Sioux in the Ghost Dance movement, which, as noted, they hoped would spiritually cleanse the lands of Euro-American invaders and restore balance. The US government, interpreting this as a call to war, responded, first, with the arrest and murder of Sioux Chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890) and then the Wounded Knee Massacre of 29 December 1890. The Sioux were then forbidden to observe the dance, but the Arapaho were given leave to continue.

The memorization of songs, prayers, and stories associated with the ritual allowed the Arapaho to retain their language, customs, and culture better than many other nations. They were also allowed to continue to observe the Sun Dance and other rituals, further preserving their traditions and heritage. Today, the Southern Arapaho in Oklahoma and Northern Arapaho in Wyoming keep these traditions, and their language, alive, passing them on to the next generation.