The Argead dynasty, the ancient Macedonian house of Dorian Greek origin, lasted from the 7th century to 310 BCE. The mythological founder of the dynasty was King Caranus but it was under Philip II of Macedon (382-226 BCE) that the Macedonian territories were greatly enlarged. Philip's son Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) then went much further, ultimately conquering Persia and reaching India.

The Foundation of the Dynasty

The land of ancient Macedon hosted the primary steps of one of the earlier empires of the world. According to the Homeric poems, as a “no man’s land”, the region was characterized by its vast and dense forests, which supplied material for the highly regarded Athenian naval fleet. According to the literary sources of the time, the Macedonian empire connected the center of the known world, with the vast, foreign, and “exotic” East. The empire’s principal central protagonists were Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, the last kings of the Argead dynasty. Although one can certainly find a certain admiration for Macedonian achievements, the literary evidence, such as the Athenian orator Demosthenes (384-322 BCE), testifies a significant spitefulness against them. The “civilized” Athenians, known for their sense of cultural superiority, did not hesitate to publicly diminish the value of their northern neighbors.

The name Argead is not mentioned in Thucydides (c. 460/455 - 399/398 BCE) or Herodotus (c. 484 – 425/413 BCE), the authors who provide most of our information on the ancient and archaic world, but they prefer another name, the Temenids. Nevertheless, the earliest mention is quoted by later historians such as Strabo (64/63 BCE to 24 CE), Appian (95-165 CE), and Pausanias (110-180 CE). The Latin historian Justin (his life’s dating is uncertain) in his Philippic Histories and the Boeotian historian Plutarch (46-119 CE) identify Caranus as the founder of the seemingly not-so-famous Macedonian dynasty. It is revealed that the Delphic oracle directed Caranus to reach Emathia with his Greek companions, and found Aigai, as ktistes, which means 'builders'. According to the story, Caranus had to follow some goats to find the exact place for the foundation of his colony. In addition, according to Justin, Perdiccas is regarded as a direct heir of Caranus.

In contrast, Herodotus states the origin of the dynasty lies in Perdiccas of Argos, a descendant of the Temenids of Argos, whose lineage led to Hercules, but as he confesses elsewhere, Macedonians themselves held this view. It is possible then that the Greek historian presumably conveyed the local oral tradition. It is important to stress that making complex and mythological genealogical connections certainly made contact with the outside world easier. Invoking Greek descent may also have been appealing to building relations by interacting with the broader Hellenic network.

Even if the information about the Argeads is meager, the excavations in Vergina, a village in modern-day Greece, unearthed a sudden rise of new burial customs along with the cremation of dead bodies, which can be dated approximately to the middle of the 6th century BCE. The archaeological evidence can, therefore, identify a possible date for the beginning of the Macedonian kingship, as the findings indicate the burials of highly distinctive residents, quite possibly the Argead kings.

The Argead kings of Macedonia were:

- Caranus

- Perdiccas I

- Argaeus I

- Philip I

- Aeropus I

- Alketas

- Amyntas I (c. -497)

- Alexander I (c. 497-454)

- Perdiccas II (c. 454-413)

- Archelaus (413-399)

- Orestes (399-396)

- Aeropus II (396-393)

- Pausanias (c. 393)

- Amyntas II the Little (c. 393)

- Amyntas III (c. 392-370)

- Argaeus II (c. 390)

- Alexander II (370-368)

- Ptolemy Alorus (c. 368-365)

- Perdiccas III (c. 365-359)

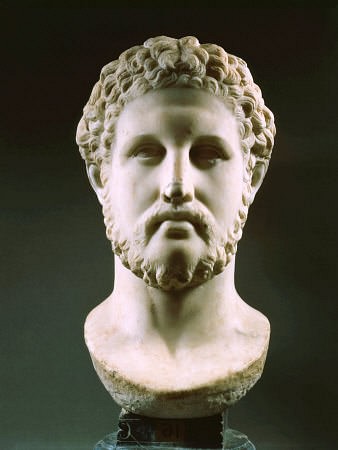

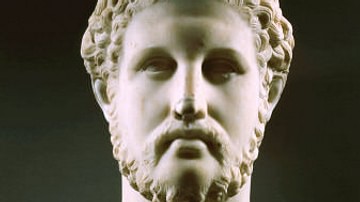

- Philip II (359-336)

- Alexander III the Great (336-323)

- Philip III Arrhidaeus (323-317)

- Alexander IV (323-310)

The relationship between Macedonia and kingship is considerably connected. Their affiliation is apparent from the 7th century BCE until the subordination to the Romans in 167 BCE. The uncertainty of the literary sources reinforces the gaps between the relationship of the basileus, the king, and his subjects, nonetheless a hypothesis can be formed. The literary sources of Herodotus, Thucydides, Diodorus, and Justin make some references to the bodies of hetairoi, the companions, the somatophylakes, the bodyguards, and the basilikoi paides, the royal pages. Modern scholars debate over two theories. On the one hand, some support that the king ruled the kingdom through some conventional laws and traditions that provided customary rights to various bodies. On the other hand, other scholars argue that the king ruled as he pleased without being guided by any constitutional laws, but enforcing his ideas according to his judgment. The most logical assumption could be in the middle. The basileus must probably have some customary laws blended with religious elements that he had to follow. Although this does not mean that he did not force his will when it seemed necessary. As the king resembled the higher seat of the hierarchy, probably no one could force the Macedonian king to act differently.

As the literary sources attest to a remarkable continuance of the Argead dynasty, we can assume that the title was hereditary. One could not possibly know if a “clear” bloodline existed, each king must have belonged to the wider family of each king. Each king to be declared king must have gained the approval of the army, who clashed their spears on shields. Certainly, each initial king had to be recognized among the army, probably by proof of his military effectiveness.

Alexander I

The earliest king we have literary evidence of is emblematically Alexander the I, the son of Perdiccas.

Alexander the father of Perdiccas and his ancestors, who are Temenidae of ancient Argive origins, first acquired what is now the coastal part of Macedonia and established themselves as kings by defending and driving the Pierians from Pieria…They acquired a narrow part of Paeonia along the Axios river down to Pella and the sea, and they occupied the land called Mygdonia beyond Axios as far as the Strymon after driving out the Edonians…The whole is called Macedonia, and Perdiccas son Alexander was its king.

(Thucydides, 2.99)

According to Thucydides, Perdiccas, the son of the Argive Caranus, played a role in the conquest of the wider area of Macedonian by occupying territories and relocating its residents. Although relocating could be a naive interpretation: the conquerors slaughtered and highly exploited the local population by selling and turning them into slaves, in parallel they accepted the allegiance of other tribes. The whole process of “won by spear” lands was rooted exponentially in the Macedonian mentality of the right to rule. Evidently, for almost 200 years, until Philip the II, the Macedonian territorial struggle unfolded between the broader regions of Macedonia.

The long reign of Alexander the I co-existed with the Persian domination of the Achaemenid empire in Asia Minor, and his role was identified by a more submissive position compared to Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and others. Nevertheless, Macedonia had a determinant function in the sanguinary events of the Persian Wars. During the Ionian Revolt in 499 BCE of various cities in Asia Minor, which were supported indirectly by Athens, Alexander, even in his efforts for an escape from Persian dominion, ended as a protectorate of the empire from the east. Herodotus characterized Alexander as strategos and basileus while including him as a Persian subject.

Although Herodotus testified the participation of Macedonian troops among the Persian forces, possibly when Alexander accompanied the Persian king invading Greece, his loyalty had to be doubted. According to the Athenian philosopher Speusippus (408 – 339/8 BCE), who inherited Plato’s Academy, Alexander was regarded as the savior of the Greek forces due to his provocation towards them, not to defend their position in the Tempe Valley in Thessaly as they originally planned. The Athenian scholar must have presumed the massive army of the “barbarian” empire invading the Greek city-states. Furthermore, the most precious testament emerges again from the historian of Halicarnassus, who mentioned Alexander’s dispatch of envoys presenting themselves to the Persian front to save the fate of the Boeotian cities. Moreover, Herodotus wanted to praise the Athenians when he reported that Mardonius, a Persian general, wanted to bring the Athenians over to his side by offering them the Great King’s forgiveness. Alexander was to encourage them to accept this offer and to dissuade them from continuing the war against the Persians. The historian wanted to transmit pride as a part of the Greek mentality by pointing out their strong disapproval. One can visualize a possible image that the Athenians or solely Herodotus had created towards the Macedonians. They have constructed such a view, that they were those who did not fight and provoked unity instead of resistance between the two opposing cultures. The signal of Alexander’s allegiance remained ambiguous, as the historian also testifies behind the scenes of the Macedonian king’s revelation of Mardonius’ plans, Darius’ general, for an unexpected attack. The story, which is surrounded by intense skepticism, informs us that at that moment Alexander sought his emancipation from Persian control.

The narrator of the Argead history declares the prosperity of the Macedonian kingdom from its access to the silver mines of Mount Athos. The mountain, now belonging to the monastic community, part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, enabled the king to mint his silver coins around 475 BCE since the Achaemenid Empire was driven out. Following the famous Pentekontaetia, the prelude of the Peloponnesian War, Macedonia kept a neutral position towards Athens. Even when the exiled Athenian general Themistocles, one of the protagonists of the naval battle of Salamis, sought shelter in Alexander’s kingdom, he subsequently moved to Persia.

Alexander I is known in history books as Alexander Philhellene. He was probably given the nickname many years after he died. It appeared for the first time in Dio Chrysostom, who wrote it in the second century BCE. The image of Alexander I as a benefactor of Greece that arose in fourth-century rhetoric might have had a considerable impact on the choice of title, which was reported in the pretext of the praise of Philip II’s ancestor towards the Greek cause. Fear of the return of the Persians and pressure from the newly formed Athenian naval confederacy, the Delian League, could result in a phenomenon in which the local communities neighboring Alexander I’s realm found it attractive to accept his leadership and to identify themselves as Macedonians, thus defining his dominion over the region. The circumstances of Alexander’s death are debated by scholars but it probably happened around 454 BCE.

Perdiccas II

The expansion of Athenian imperialism brought agitation in the territories of the kingdom, especially when the cunning Athenians took advantage of Alexander's I death and expanded their dominion through an aggressive colonial policy and a fierce diplomatic alliance with the eastern neighbors of Macedonia. As a result, a colony of importance was founded, Amphipolis, in 437 BCE at a pivotal geographical and economical position preluding the birth of the Macedonian Empire. The Athenian growth probably caused Macedonian territorial losses, as local rulers must have strongly expressed their discontent with the events. During the Peloponnesian War between the years 424–422 BCE, the famous Spartan general Brasidas led an expedition which resulted in the alliance of Sparta with the local cities, including Amphipolis. Even though the Macedonians did not participate actively in the war, they both approved the anti-Athenian ventures in the north, while at the same time continued the supply of timber to the city of Theseus, the mythical founder of Athens. The only military actions Perdiccas II took was over interior territorial matters over the local ethne like the Lynkestians - nowadays the tribe has to be located around the city of Bitola in North Macedonia. It must be noted that the capabilities of Perdiccas II were limited, and certainly, the neutrality at that moment proved most valuable. Perdiccas managed to keep the Macedonian kingdom functioning during one of the greatest disputes that sculptured the history of the classical Greek world.

The Apex of the Dynasty

The successor of Perdiccas II, Archelaus, ruled for almost 14 years, which is almost double the approximately seven years that Perdiccas II ruled Macedonia. Between the two kings, eight Argeads ruled for 40 years, each for a few years. Then came Philip II in 359 BCE who brought a new eminence to the Macedonian kingdom. During this agitated period, the kingdom interacted with various cities but experienced issues of internal rulership. The Illyrian tribes from the north, known for their continuous raids, ravaged the Macedonian plains intensifying, even more, the struggle for survival of the kingdom. These threats resulted in dark political and military episodes such as Amyntas III fleeing the kingdom in the face of an Illyrian invasion or his son being killed in combat against Illyrian tribes.

Nonetheless, apart from the military’s attributes, the Macedonians were known for the shrewdness of their diplomats, who were raised in a region of well-established infrastructures in Pella and in Dium, the main centers of the kingdom. Despite the improvements in defensive constructions and trade networks, the army proved their Achilles heel. Like any other significant character of world history, Philip II depended on this kingdom to build the roots of what the Macedonian Empire became best known for: the unification of three continents Africa, Asia, and Europe. He was the coordinator of the illustrious Macedonian legacy. He managed to put together the scattered territorial resources and administer the population of the wider kingdom. His diplomatic skills, together with his martial dynamism, were the tools of the formulation of the competitive kingdom of Pella. However, Philip's murder in 336 BCE unleashed the wrath of his son against the long-desired Persia.

The Argead dynasty reached its peak during the conquest by Alexander the Great of the little-known east world. He became “great” after the successful campaign against Darius III (336-330 BCE) when in 334 BCE he invaded the Achaemenid Empire. He began in the cities of Sardis and Ephesus. Alexander, a year later, was victorious at the battle of Issus, enabling his forces to move further into the Asian continent. After the sacking of the Phoenician cities of Tyre, Sion, and Baalbek, in 331 BCE the kingdom of Egypt submitted to his early empire. The ambitious Macedonian king swiftly defeated Darius in Gaugamela the same year, forcing him to flee. The retreat of the Persian ruler enabled Alexander to capture Babylon and Susa, the very heart of the eastern empire. In 330 BCE the son of Philip marched rapidly against Persepolis, delivering a final blow against the last defender of the Achaemenid Empire Ariobarzanes (386-330 BCE). Alexander reduced the great Persian city to ashes. The historian Diodorus Siculus (90-30 BCE) would promote the continuance of the endless fatalities of war by justifying them as countermeasures to the sack of the Athenian Acropolis by Xerxes in 480 BCE.

In 330 BCE, the assassination of Darius III by his men authorized Alexander to declare himself the king of Asia, evidently forming the core of his empire. The success of the Persian campaign must have certainly boosted the Macedonian king's arrogance, which led him to march further east. He wasted no time and between 330-327 BCE he advanced against the Scythians and the residents of Bactria and Sogdiana, who bent under his will. Even though Alexander was a conqueror, he was respected due to the many cities he founded. The newly founded cities worked as stations of supply redistribution for the military campaigns, as well as centers for the placement of Macedonian veterans. Additionally, over the next year, Alexander subdued several population groups in India; he overcame the Porus of Paurava in the Hydaspes River. Finally, in 323 BCE Alexander, after enduring the pain of a ten-day fever, died in his palace in Babylon.

The Decline of the Dynasty

After the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, Cassander the king of Macedonia from 305 BCE until 297 BCE put an end to the Argead dynasty by having Philip III Arrhideaus, the son of Philip the II and also Alexander the IV (the son of Roxana and Alexander the Great), assassinated in 317 and 310 BCE, respectively. Cassander's actions were based on his interest in fighting for power in the infamous Wars of the Diadochi, the successors of Alexander III. Perhaps the most significant contribution of Cassander was the foundation of Thessaloniki. The colony was a result of a synoecism of the local communities and took the name - the win of Thessaly - from his wife, the daughter of Philip the II, who named her after his great victory in Thessaly against the Phocaeans. The city flourished through the ages and now, in the modern-day, echoes the significant past of a plethora of civilizations and cultures through its many archaeological and architectural remains.