Aristides (520s – c. 467 BCE) was an Athenian statesman and military commander who gained the honorific title 'the Just' through his consistent selfless behaviour in public office. Although ostracized by the Athenian assembly, Aristides returned to command troops with great success at the battles of Salamis and Plataea during the Persian Wars of the early 5th century BCE. He is the subject of one of Plutarch's Lives biographies.

Early Life & Career

Aristides (also spelt Aristeides) was born sometime in the 520s BCE in the Athenian deme of Alopeke. His father was Lysimachus, and so he was born into the Athenian aristocracy, even if ancient sources somewhat exaggerated his early poverty. He was wealthy enough to support Greek plays in competition, several of which he won, but according to Plutarch he always shunned opportunities for financial gain. As a cousin of the wealthy Callias, and good friend of the influential Cleisthenes, he had powerful political connections. Of his early career we know that Aristides was possibly a general at the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE (Plutarch thought so but Herodotus fails to mention him) and was made archon (the highest political position in Athens) in 489 BCE.

Aristides the Just

Ancient writers gave the politician the title of 'Aristides the Just' and portrayed him as an honest and principled member of the Athenian government, a portrait in stark contrast to the reputation of his contemporary and greatest political opponent Themistocles. Herodotus describes him thus, 'I have come to believe through my inquiries into his character that he was actually the best and most just of all the Athenians' (Bk. 8.79.1). Plutarch describes several episodes which, for him, illustrated the upright character of Aristides. He would withdraw his own proposals in the assembly if swayed by arguments from the opposition, he once gave up his right to military command because he considered Miltiades the more talented general, scrupulously guarded the war-booty from Marathon, gave a fair hearing to someone who had done him personal harm, and he exposed cases of political corruption.

Ostracism

Nevertheless, Aristides' reputation did not save him from ostracism (exile) in 482 BCE following accusations of excessive sympathies with the Persians and the crafty political machinations of Themistocles. According to Plutarch, one assembly member voted against Aristides simply because he was fed up with hearing the politician constantly referred to as 'the Just'. Indeed, this story was another example of Aristides' just nature as, when the illiterate voter, not realizing who he was talking to, asked Aristides to scratch for him the name of Aristides on his piece of pottery in order to cast his vote, instead of walking by or revealing his identity, Aristides did what the voter asked and wrote his name on the pottery which would contribute to his exile. One such pottery piece can be seen today in the Agora Museum of Athens, is it too fanciful to hope that it could be the one which Aristides wrote? Aristides' exile did not last long as, unusually, he was given a pardon and allowed to return to the city in 480 BCE in order to meet the new threat of invasion by the Persian king Xerxes.

Military Commands

In 480 BCE Aristides successfully commanded a force of hoplites in an attack on the island of Psyttaleia in the final stages of the battle of Salamis. He had also appeared prior to the battle when the Greeks were wavering as whether to attack or not the Persian fleet, but when Aristides informed the overall commander Themistocles that the Greeks had already been encircled in the narrow straits, the battle was on. Aristides commanded again, this time the 8,000 Athenian hoplites, at the battle of Plataea in Boeotia in 479 BCE. When faced with the protests of the Tegeans as to which position was more prestigious and theirs by right, Aristides told them,

We did not come here to quarrel with our allies, but to fight our enemies, not to boast about our ancestors, but to show our courage in defence of Greece. This battle will prove clearly enough how much any city or general or private soldier is worth to Greece. (Plutarch, 123)

In the event, of course, the combined Greek force defeated the Persians and finally ended Xerxes' territorial ambitions in Greece. According to Plutarch, Aristides proposed forming a joint Hellenic army of cavalry and hoplites but the Athenians rejected it, probably because the democracy did not want to fund an aristocratic-dominated cavalry. Another proposal by Aristides was enacted, to hold commemorative games every four years at Plataea which would involve athletes from all over Greece.

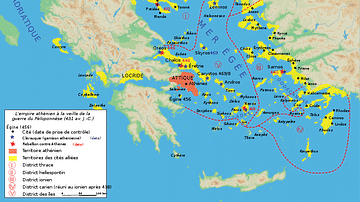

Aristides was again on official duty when he was selected as the envoy sent by Athens to Sparta shortly after the battle to convince them of Athens' benign intentions in rebuilding their fortifications. The last record of Aristides is when the Delian League, a mutual alliance to protect Greek cities from any future attack, was formed in 478 BCE. Aristides was given the task of assessing how much tribute particular states should pay to Athens and oversee the swearing of the oaths of allegiance. No doubt he was chosen, at least in part, because of his reputation as a fair-minded leader. According to Plutarch, Aristides was buried on his estate at Phalerum, just outside Athens.