The Arsacid (Arshakuni) dynasty of Armenia ruled that kingdom from 12 CE to 428 CE. A branch of the Arsacid dynasty of Parthia, the Armenian princes also played out a prolonged balancing act by remaining friendly to the other great power of the period and region: Rome. As so often before, Armenia continued to be a hotly disputed territory between Persia and Rome with both sides intervening directly into affairs of state and occasionally sending their armies to back their claims. The period saw great social changes in Armenia, too; notably the official adoption of Christianity in the early 4th century CE and the invention of the Armenian alphabet. The dynasty, as well as the 1000-year-old monarchic system of Armenia, ended with the installation of Persian viceroys in a system which would last until the Arab invasions of the 7th century CE.

The period of history of both Armenia and the region during the reign of the Arsacids was a complex one and the kingdom remained, as it already had been for centuries, a coveted piece in the strategic board game of empires played out by Europe and Asia's two superpowers: Rome and Persia. To add an additional layer of difficulty, the historical record is patchy at best, a situation here starkly summarised by Professor of Armenian and Near Eastern History R. G. Hovannisian:

Our knowledge of the events or even the chronology of Armenia during this complicated period remains fragmentary in the extreme, confused and still highly debated. (63)

Fortunately, despite these difficulties, a general overview can be acquired by piecing together the works of various Roman authors, early Christian authors, inscriptions, coinage and archaeology. It must always be born in mind, though, that such questions as who supported who, when and why have answers very often made opaque by missing information and national bias - both ancient and modern.

Rome & Parthia

The volatile political reality of Armenia in the second half of the 1st century BCE is reflected in the short reigns and frequent change of monarchs of the ruling Artaxiad (Artashesian) dynasty: nine rulers from 30 BCE to the first decade of the 1st century CE. The decline of the Artaxiads was in part due to the internal factions which had been created by the nobility splitting into either pro-Roman or pro-Parthian factions when the kingdom was caught in regional power politics. In unclear circumstances, the Artaxiads were succeeded by the next dynasty to dominate Armenian affairs, the Arsacid (Arshakuni) dynasty, when their founder, Vonon (Vonones) took the throne in 12 CE with Roman backing. However, the trend of short-reigning monarchs would continue until the arrival of Tiridates (Trad), considered by some to be the real founder of the Arsacid dynasty.

Tiridates I

Tiridates I of Armenia (r. 63 - 75 or 88 CE) was the brother of the Parthian king Vologases I (r. c. 51-78 CE) who invaded Armenia in 52 CE for the specific purpose of setting Tiridates on the throne. The Romans were not content to let Parthia into what they considered a buffer zone between the two powers and, in 54 CE, Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE) sent an army under his best general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. Vologases had, by that time, been forced to withdraw to deal with internal troubles in Parthia but Tiridates remained at Artaxata and he was supported by most of the Armenians.

Corbulo proved to be a very capable field commander and by 60 CE he had taken the two most important Armenian cites - Artaxata and Tigranocerta - and could claim to rule over all of the kingdom of Armenia. Parthia responded by sending an army which won a victory against the Romans (significantly, perhaps, no longer commanded by Corbulo). In 63 CE the Romans and Corbulo returned and their threat was sufficient for the Treaty of Rhandia to be drawn up. It was now agreed that Parthia had the right to nominate Armenian kings, but Rome the right to crown them. Nero was thus given the privilege of crowning Tiridates in Rome in a lavish spectacle that did much to show the power and extent of the Roman Empire. The Romans, just to be on the safe side, then placed a handful of garrisons in the area. Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) made sure that no more territories would fall to the Parthian ruling dynasty by annexing the neighbouring kingdoms of Commagene and Lesser Armenia in 72 CE. A period of peace followed and Tiridates was able to build a new summer residence at Garni which had the Roman baths, temple and gardens typical of the Classical world.

Trajan & Roman Dominance

The region erupted again when the sons of Pacorus II of Parthia (r. 78-105 CE), Axidares and Osroes I, squabbled over the Armenian throne with Osroes removing Axidares and making his other brother Parthamasiris the king of Armenia (possible reign 113-115 CE). This caused the already precarious balance of regional politics to be upturned completely when Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE), using the excuse of not being consulted on the change, grabbed the moment and annexed Armenia for Rome. He then declared war on Parthia in 114 CE. Parthamasiris had given in to the Roman emperor when he arrived with his army but Trajan rejected his submission and Armenia was made a province of the Roman Empire and administered alongside Cappadocia.

Poor Parthamasiris was given the honour of a Roman knightly escort to get back to Parthia but was murdered on the way, probably by the knights who were under Trajan's orders. Trajan had taken no chances with the lower sections of the population either and he left two army divisions and built a fort at Artaxata to ensure Armenia stayed a Roman province. Still, when the emperor died in 117 CE rebellions began to spread and his successor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), much less enthusiastic about keeping the bothersome province, allowed it to become independent. In reality, this merely gave it up to the Parthians but Armenia would continue to be disputed territory well into the 4th century CE.

In 117 CE the new Arsacid ruler Vagharsh I was crowned king of Armenia and he would rule until 140 CE during which time he moved the official royal residence to Vagharshapat while Artashat (Artaxata) remained the capital. Roman oversight did not go away, as is confirmed by Antoninus Pius' (r. 138-161 CE) selection of Sohaemos as the new king in 140 CE. When the king was deposed in 160 CE Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-169 CE) sent an army to restore the monarch (163 CE) who would then rule until 180 or 185 CE. Relations with Rome were not always so cordial and Artaxata was sacked in 166 CE before both Rome and Persia agreed the city was to become one of the official trading points between the two empires. As a consequence, the city prospered thereafter.

Political & Social Structures

The constant warfare of this period had political repercussions within Armenia during the Arsacid dynasty. There rose a class of landed aristocracy whose ability to raise bodies of armed men to support the royal family meant that they grew in influence - the king needed their armies and could offer land and titles in return. These local princes or nakharars, were based on the hereditary clans of ancient Armenia and they governed their own extensive lands as autonomous fiefdoms. Below these feudal lords, as recorded in the anonymous 5th century CE History of Armenia, were a class of knights, the azats, then the ordinary citizens or ramiks, the peasants or shinakans, and finally the slaves or struks.

The king ruled as an absolute monarch but his reliance on the nakharars did mean in practice he had to at least to consult them on important matters of policy. The general populace was governed by local administrators controlled by several government ministries which were responsible for such essentials as tax collection, justice, and public works projects like the building of roads, fortresses and irrigation systems. It has been argued that the constant invasions and the testing of nakharar loyalties, along with the general necessity to all pull together or be conquered, helped build a national spirit and that, for the first time, ancient Armenia began to feel and act like a unified country.

Sasanian Empire

In 224 CE the Arsacid dynasty in Parthia was overthrown by Ardasir (aka Artashir Papakan), founder of the Sasanid dynasty which would rule until 651 CE. The change marked a more aggressive foreign policy from Persia regarding Armenia which culminated in a full-scale invasion by the Sasanids in 252 CE. The Armenian Arsacid kings, with such close blood ties to the vanquished Arsacids in Persia, posed a threat of legitimacy to the new Sasanid order. The Sasanids won several major victories against Rome in this period, including the capture of Emperor Valerian (r. 253-260 CE) which ended his reign. Rome came back strongly, though, from the reign of Aurelian (270-275 CE) after a period of chaotic rule and several short-reigning emperors preoccupied the Romans with internal affairs. When the dust finally settled again the kingdom of Armenia found itself divided up between Rome and Persia with the Arsacids continuing to rule only western Armenia. In 298 CE, under the auspices of Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE), Armenia was unified with Tiridates IV (Trdat IV) as king (r. c. 298 - c. 330 CE) - one of the great rulers of the Arsacid dynasty.

Tiridates the Great

Tiridates IV (or III), or Tiridates the Great as he would become known, set about centralising his kingdom and reorganising the provinces and their governors. Land surveys were also carried out to better identify tax obligations; the king was determined to make Armenia great once again and regain some of the lost glitter not seen since the days of Tigranes the Great in the first half of the 1st century BCE.

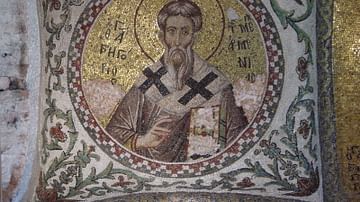

Then came a momentous policy change. Armenia officially adopted Christianity c. 314 CE, if not earlier, as tradition records that Tiridates IV was converted in 301 CE by Saint Gregory the Illuminator. Although it shifted Armenia closer to Roman religious culture, one consequence of the move was that the persecution of the religion by Persia helped to create a more fiercely independent state. Saint Gregory, then known as Grigor Lusavorich, was made the first bishop of Armenia in 314 CE. Tiridates IV may also have adopted Christianity for internal political reasons - the end of the pagan religion (with its heady mix of Greek, Persian, Semitic and local gods) was a fine excuse to confiscate the old temple treasuries which were jealously guarded by a hereditary class of priests. Further, a monotheistic religion with the monarch as God's representative on earth might well instill greater loyalties from his nobles and people in general.

In the 330s CE, Tiridates' successor, Khosrov III (r. c. 330-338 CE), notably founded the city of Dvin. In the same period the Sasanids again became more ambitious to rule directly over Armenia, especially during the reign of the Sasanid king Shapur III (r. 383-388 CE). The Sasanids first deposed Tiran in 338 CE and then Arshak II in 350 CE (reign dates for both are disputed). Several Armenian cities were attacked by Sasanid forces in 368 and 369 CE and the matter of who would rule Armenia was only to be resolved in c. 387 CE. It was then that emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) and Shapur III agreed to formally divide Armenia between the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and Sassanid Persia.

Fall of the Arsacids

During the reign of the last great Arsacid monarch, Vramshapuh (r. 389 or 401 - 415 or 417 CE) there were significant cultural developments in Armenia. In 405 CE the Armenian alphabet was invented by Mesrop Mashtots and the Bible translated into that language, helping to further spread and entrench Christianity in Armenia. Politically, though, it was time for a change. The last Arsacid ruler was Artashes IV (r. 422-428 CE) after the Armenian crown, unable to repress the pro-Persian and anti-Christian factions at court, was abolished by Persia and viceroy rulers, the marzpans, were installed, in a situation which would not change until the mid-7th century CE.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.