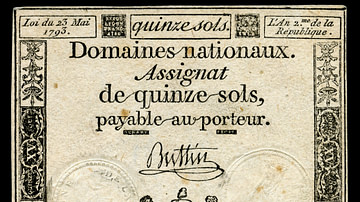

The assignat was a paper bill issued by France between 1789 and 1796, during the French Revolution (1789-1799). First issued in the form of bonds, the assignat was meant to stimulate France's economy as a quick means to pay off national debt. Yet, assignats soon devolved into a paper currency, the mass production of which led to inflation and depreciation.

Originally issued in December 1789, assignats were backed by the value of national properties that the National Constituent Assembly had recently seized from the crown and the Catholic Church. The Assembly's plan was to supply their creditors with assignats, which were bonds with a 5 percent interest rate, who could redeem them to purchase these national lands. Despite initial success, assignats quickly decreased in value, especially after they had started to be used as a currency. This was due to the French public's distrust of paper money, investors' lack of confidence in the stability and credibility of the revolutionary government, as well as the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). By 1797, the assignats were out of circulation and had been replaced by the franc.

Prelude: Financial Crisis

By November 1789, it would not have been unreasonable for one to assume that the French Revolution had come to an end. The National Constituent Assembly, birthed from the dramatics of the Estates-General of 1789, had come to dominate the French political scene. Having abolished feudalism and suppressed the Catholic Church's right to collect tithes in the August Decrees, the Assembly had gone on to draft the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a landmark human rights document that, among other things, denied the French kings' claim to rule by divine right. At the same time, popular uprisings such as the Storming of the Bastille in July and the Women's March on Versailles in October gradually stripped King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) of his power, to the point that he and his family were now virtual prisoners of the Revolution. The oppressive Ancien Régime, it seemed, had been shattered. It was now left to the Assembly to craft something new from the pieces.

This would prove a daunting task. Of the two glaring issues that had originally forced Louis XVI to convene the Estates-General back in May, namely financial crisis and societal reform, the former had been largely ignored in the dramatics of the revolutionary summer. The financial crisis was the result of decades' worth of wanton spending in the form of expensive military endeavors and frivolous building projects, as well as incoherent systems of taxation that differed from region to region. After taking power, the Assembly had inadvertently made the system of taxation even more confusing. Upon abolishing such taxes as the hated gabelle (salt tax) and indirect taxes (equivalent to modern sales taxes), the Assembly had endeared itself to the people to the detriment of its own coffers. Matters were made worse by the fact that the Assembly was having difficulty collecting the taxes it had authorized, as many French citizens were under the false impression that they did not have to pay anything at all. In late 1789, therefore, tax collection fell far short of its goals.

Now, in November, the issue could not be ignored any longer, as national bankruptcy became practically inevitable. Amidst an atmosphere of urgency, the eyes of France turned to Jacques Necker (1732-1804), the Swiss banker turned chief royal minister who was regarded by many as a brilliant financial mind as well as a champion of the people. But Necker's solution would prove to be less populist than many in the Assembly might have hoped. Citing the Bank of England as an example, Necker proposed the creation of a French national bank, from which a limited supply of paper money could be issued to pay off the country's short-term debts, the deadlines for which were rapidly approaching.

This idea was opposed in the Assembly for two reasons. The first was due to France's previous unpleasant experience with paper currency. In 1720, Scottish economist John Law had set up a state bank on behalf of the juvenile king Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774), which issued paper bank notes. After a short period of success, Law's economic system collapsed, leaving thousands of French families with nothing but mountains of worthless paper money. France had been haunted by the memory and resisted the use of paper currencies ever since. The second reason the Assembly disapproved of Necker's plan was its reluctance to put any political power into the hands of Europe's leading capitalists. The Assembly, which had just banished corrupt venal offices, was not about to put power back into the hands of the same bankers who were believed by many to have gotten the kingdom into this predicament in the first place.

Most vocal in the opposition to Necker's solution was Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791), who disliked the Swiss banker personally and was undoubtedly pleased to thwart him. As an alternative plan, Mirabeau suggested that the state should issue not paper money but bonds secured against the value of visible assets to ensure that they would not collapse as had Law's scheme 60 years before. The assets Mirabeau proposed to back the value of the bonds were none other than the properties that the Assembly had recently seized from the crown and the clergy, the combined value of which was estimated at 400 million livres. Arguing that the credit of the state, ensured by the Assembly itself, was superior to any bank, Mirabeau won the day. On 21 December, the Assembly began the process of selling the confiscated lands and ordered that the bonds, named assignats, be issued.

At this early point in their conception, assignats were released in denominations of 1,000 livres, at an interest rate of 5 percent. The state would use them to pay its creditors, who in return could redeem them to acquire national lands. These notes were therefore not intended to be in perpetual circulation and would be retired after the sales of the properties. The release of the original assignat turned out to be a grand success, the value of which was as trusted as gold. But even this was not enough to save France from the specter of economic ruin, and it soon became clear that something more substantial had to be done.

The Paper Money Debate

By the summer of 1790, the Assembly was again faced with the prospect of rapidly approaching bankruptcy. The treasury was now critically short on cash, thanks in part to the shallow stream of taxes that had barely begun to refill France's coffers. The Revolution's elimination of certain public offices also further stymied economic growth, while foreign investors' concerns about the direction the Revolution was taking threatened the credibility of the French government. The Assembly resumed debate on how to approach the issue. Some deputies proposed demonetizing gold and adopting a silver standard, while others advocated for the sale of all remaining national properties at an estimated value of 800 million livres, which would have been enough to pay off most of the remaining debt immediately.

Another option was to convert the assignat into legal tender. This idea was championed by the outspoken Mirabeau, who argued that the economy could not grow without more monetary assets in circulation:

We have a pressing need of means to support business, and the assignat-money, besides paying off the national debt, will also provide a greater source of economic activity. (Davidson, 56)

Mirabeau was opposed by other prominent voices in the Assembly, such as Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754-1838), bishop of Autun, whose concerns harkened back to the Law debacle of 1720. Talleyrand said:

In reality, there is at present only one dominant currency, namely silver. If you circulate paper, it will be paper. You will, I grant, command that this paper not lose its value. But you will not be able to prevent silver from gaining in value, and that will be tantamount to the same thing. You will ensure that an assignat of 1,000 livres must be accepted for the sum of 1,000 livres. But you will never be able to force anyone to give 1,000 livres in silver for an assignat of 1,000 livres. And because of this the whole system will collapse. (Furet, 428)

In essence, Talleyrand was echoing the economic principle known as Gresham's Law, which states that "bad money drives out good" (Davidson, 57). His fear was that the metal coinage would become more valuable than the assignats, which would cause mass inflation and drive up the price of ordinary goods such as bread. Mirabeau countered this first by assuring his fellow deputies that the assignats would still be backed by properties of great value, and then by equating support for the assignat with support for the Revolution itself. Many of the deputies, lacking sufficient education in economics, chose the force of Mirabeau's personality over the soundness of Talleyrand's logic. In a vote of 518-423, the Assembly chose to establish a currency based on the assignat and issued 800 million livres worth of the note. The assignat would henceforth be assigned at a fixed rate of exchange with metal currency.

Necker, still a proponent of a national bank, was unnerved by this decision, believing it would lead to the economic ruin of France. Yet, now that a decision had been made, it would be unpatriotic to question the assignat's usefulness, as doing so would be tantamount to questioning the wisdom of the people to govern themselves. Therefore, Necker could either adhere to the program or resign. Realizing his influence had long been fading, Necker chose resignation and left for a self-imposed exile in Switzerland on 3 September 1790. The exit of this man, once the favorite of the commons, was greeted by general indifference by the population, exemplifying the volatility of popular opinion during the Revolution.

Rising Inflation

Meanwhile, Necker and Talleyrand were already being proven right. Already by April 1790, the assignat had depreciated by 10 percent compared with metal currency. Prices were rising higher than expected, which the Constituent Assembly combatted by issuing more assignats. In early June 1791, it authorized a further 100 million livres worth to be put into circulation, along with an additional 480 million later the same month. At the same time, a crisis of confidence in the assignat was brewing; Louis XVI's failed attempt to flee Paris and instigate a counter-revolution in the Flight to Varennes underscored that the king would never truly accept the new constitution. This glaring point of discord within the French government naturally caused concern in relation to the assignat's value, which was guaranteed not by a bank, but by the revolutionary government itself. The value of the currency dropped. Subsequently, French landowners stubbornly refused to pay their taxes, and countryside farmers refused to accept assignats as payment for their produce.

As the national deficit continued to climb, the Assembly (now rebranded as the Legislative Assembly) continued to double down, issuing new batches of assignats in December 1791 and January 1792. These new batches included new, small denominations of 10, 15, 25, and 50 sous. The intention was for these new notes to further replace metal coinage in circulation. Yet, when France declared war on Austria and Prussia in April, kicking off the French Revolutionary Wars, the assignat's value plummeted even further, falling by as much as 48 percent. War meant that more money had to be spent feeding and equipping soldiers, further worsening the economic problem, and pumping even more assignats into circulation. Meanwhile, the refusal of farmers to accept assignats as payment led to food shortages, and near-famine in some places. In November 1792, Jacobin rising star Louis Antoine de Saint-Just summed up the situation when he stated, "I no longer see anything in the State but misery, pride, and paper" (Furet, 430).

As France continued to pump out assignats, it had to continue to back them up with valuable assets. As evidenced by the words "Mortgaged on the National Estates" that appeared on all notes printed between 1791 and 1795, the assignat's value was still backed by national properties. However, as the Legislative Assembly (and later its successor, the National Convention) ran out of the properties seized in 1789, it was forced to supply itself with new lands. With each issuance of assignats came another seizure of properties; in 1792, lands belonging to emigres who fled France were seized, followed by possessions of their relatives the following year. When French armies occupied Belgium and the Palatinate in 1794, properties belonging to those nations' clergy and nobility were also confiscated to back the assignat.

These measures allowed the new French Republic to have almost 3.7 billion livres worth of assignats in circulation by 1793. Yet, even as French armies defeated their enemies on fields of battle, the National Convention was faced with the task of defeating rising inflation at home. There were multiple ways it attempted to achieve this. First, the Convention tried to take older assignats out of circulation. In July 1793, six months after the trial and execution of Louis XVI, the Convention attempted to retire all the notes issued during the king's reign which bore his likeness. This backfired, however, as the new scarcity of the Louis XVI notes made them increase in value over the newer republican assignats. The Convention still managed to take 600 million livres worth of assignats out of circulation with this decree, although it hardly did much to slow inflation.

The French Republic next tried to eliminate precious metals entirely from the French economy. In autumn 1793, as the Reign of Terror ramped up, citizens were encouraged to exchange any metal coinage they possessed for an equal value of assignats in order to prove their devotion to the Revolution. This measure was hardly successful, as it probably contributed to further hoarding of gold. The Republic, now controlled by the Committee of Public Safety, finally tried to put price control on bread and flour to stop rising costs with the Law of the General Maximum. This law extended price gougers and hoarders to fall into the category of 'enemies of the Revolution' as defined by the Law of Suspects. Yet this also backfired, as the cap on prices led to decreased food production.

The System Collapses

In late 1793, millions of counterfeited assignats, manufactured in London, were in circulation within France, as part of a deliberate attempt by the government of Great Britain to cripple France's war effort. Yet, despite its rapidly depreciating value, the French government was still able to use the assignat to field over a million soldiers. This led to stunning battlefield victories over Coalition forces, the plunder from which helped to fill the treasury. With this new influx of wealth, the depreciation of the paper currency became somewhat less of a pressing issue.

In July 1794, the Thermidorian Reaction led to the fall of the Committee of Public Safety and an end to the Terror. The new government, known as the Directory, was less concerned about paper money than the previous one had been. Still, the treasury could not yet be sustained without the currency, so in January 1795, the Thermidorians authorized the printing of new bills totaling 7 billion livres. By now, an assignat that was supposedly worth 1,000 livres had the purchasing power of only 80 livres in silver. Many saw it necessary to find a way to retire the assignat quickly and return to a strictly metal currency.

The Directory tried once more to institute a paper currency, replacing production of the assignat with a new banknote called the mandats territorial in 1796. This was instituted as an attempt to reset the currency; since the mandats could be used to purchase national properties, they theoretically shared an equal value with silver. However, due to the nature of assignats still in circulation, the mandat became inevitably linked to the assignat, and quickly declined in value along with it.

The failure of the mandat forced the Directory to officially return to a metallic currency in February 1797. By now, the plunder brought in by wartime victories was such that the Republic did not have to use national properties to back its currencies. When Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) came to power in 1799, he opposed any currency not backed by the value of gold or silver. The French Franc, reintroduced by the Directory in 1795, became the national currency, which it would remain until 1999 when it was officially replaced by the euro.

The failure of the assignat seems obvious in hindsight. Historian Michel Bruguière points out:

the overall condition of the French economy at the end…of the eighteenth century, especially in a time of war, did not warrant large-scale issuance of paper currency. Any sudden and massive infusion of money into the economy could therefore have had no other result than to fuel inflation. (Furet, 436)

The assignats were part of the attempt by the revolutionaries to tear down and rebuild every facet of the old regime. Of all the ways in which the French Revolution could be considered as having succeeded, the experiment of the assignat is not one of them.